Remember the good ol’ days of 1974? Watergate, the Rumble in the Jungle, lots of civil wars and stuff. Everybody did drugs and wore weird clothes, probably. StAR is taking you back to a simpler time, with weird glam rock, shitty Japanese horror movies, and a long poem you probably won’t read.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

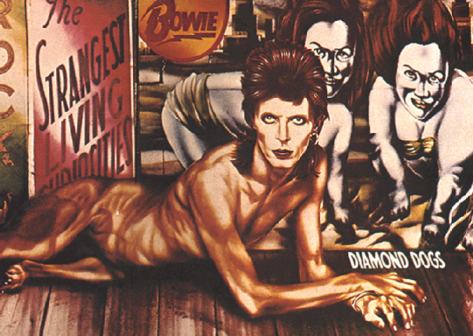

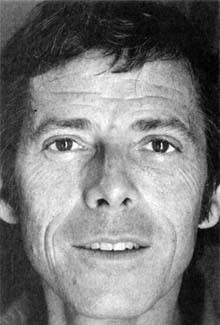

The Future Will Be Glittery: David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs

by Tina Vachovsky

In 1972, the eccentric, glitter-adorned Ziggy Stardust graced our Earth. The next year, his swift departure, at the height of success, shocked us almost as much as his arrival. But in ‘74, his equally flamboyant creator David Bowie reclaims the trashy rock star identity sans persona. His album, Diamond Dogs, imagines a post-apocalyptic world loosely based around Orwell’s 1984, but induced with the glam style so familiar of Bowie. And what better time than a decade until the famed year to reinvent the novel? Bowie evokes a different kind of future, one that touches on the same authoritarian themes, but guesses at a parallel Ziggy-esque anti-culture. The title itself, Diamond Dogs, references the sleazy yet fabulous, lowly yet ostentatious, what David Bowie both reflected in himself and foresaw in the youth.

Bowie opens his album with the haunting “Future Legend,” in which he narrates our imminent environment, a chaotic post-Earth plagued by strange creatures and death. However what initially comes off as sinister morphs into entertainment as “Future Legend” leads into the title track, the same world, but imbued with funk rhythms and glamorous characters (the Halloween Jack that slides down a rope instead of taking the elevator). The song prepares us for the remainder of the album, which likewise juggles the fear of where our so-called progress will lead us with an unexpected levity.

Take the single, the inarguably catchy “Rebel Rebel.” The title implies rebellion, but Bowie instead describes a sort of “I don’t care anymore” outlook. By following the lyrics “She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl” and “You’ve torn your dress, your face is a mess” with “Hot tramp, I love you so” to the backdrop of a repetitive dance-inducing riff, Bowie suggests ambivalence over resistance. In other words, the future may suck, so we might as well have a good time.

And we do, when we listen to Bowie’s now familiar feminine articulations on fairly low registers and distinctly funk-influenced guitars and drums. Orwell’s 1984 may have warned against the future, but Bowie’s Diamond Dogs accepts that we are too late to change it. Even the songs that directly reference Orwell, “1984” and “Big Brother”, among others, do so jovially, satirically recognizing the unavoidable authority but also acknowledging its empty nature. The earlier introduced chaos, the dance-oriented beats, and the overarching presence of glam all seem to question whether it counts as control if the population doesn’t care (about anything other than glitter, that is).

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

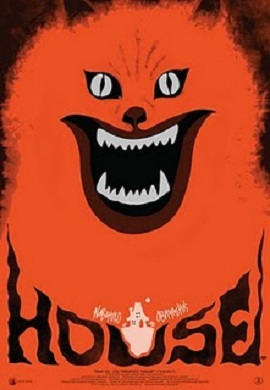

What, Sue? Hausu?: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Hausu

by Adam Schorin

1974 was a great year for movies. Francis Ford Coppola won both the Palme D’Or, for The Conversation, and the Best Picture Oscar, for The Godfather II. Mel Brooks released Young Frankenstein and (AND) Blazing Saddles. There was also Chinatown, A Woman Under the Influence, Lenny, The Towering Inferno, Murder on the Orient Express, and The Man with the Golden Gun, the only Bond movie in which a woman willingly has sex with him after he beats up a mentally ill midget. So a great year, a tremendous year. (Rivaled only, perhaps, by 1976, which gave us Taxi Driver, Network, All the President’s Men, and Rocky.) I should have had no trouble, then, in picking a movie to write about. But I did. There were so many good options and nothing hit the criteria I made up: weird, not widely known, and amazing. Some of these came close—A Woman Under the Influence was almost weird enough—but none hit the jackpot.

So I cheated. The film in this review, though developed, maybe, in 1974 and written in ‘75, didn’t actually hit theaters until a few years later, in 1977. It didn’t even make it to American audiences until the new millennium, when Janus Films purchased the distribution rights. What is this forgotten masterpiece? This cinematic achievement for which I’d dare ignore chronological fact? Hausu—or, as I say it in my head, Hausu!!!, with at least three exclamation points, just like that. Rarely does talking about a film make me so excited, so I hope you’ll allow me to bend history slightly and say that, for the purposes of this article, provided you don’t Wikipedia-fact-check me, Hausu came out in 1974. Agreed? Doesn’t matter. Allow me to present the best worst film in the history of all things ever.

In what we’re now calling 1974, ad-director and likely LSD addict Nobuhiko Obayashi was commissioned by Toho Studios to make a Japanese version of Jaws. Instead, he asked his pre-teen to tell him what kept her up at night. She told him about a murderous house, death by pillow fight, and a human head flying out of a well. Obayashi, father extraordinaire, put them all in his movie, which had nothing to do with Jaws. Hausu tells the story of seven schoolgirls, named like the seven dwarves (Fantasy, Gorgeous, Prof, Kung Fu, etc.—Mac is the fat one, which by Japanese standards means slightly underweight), who go on vacation to a remote mansion belonging to Gorgeous’s elderly aunt. A mundane start, sure, but once they are at the house (the “hausu” of the title), shit starts to get weird: the house turns out to be bloodthirsty killer, the aunt’s cat is evil (and somehow spiritually connected to the house), the piano eats anyone who tries to play it, and there’s a dancing skeleton boogying from room to room. Hausu!!!!

For a film with such gratuitous violence, it’s amazing how little of it is actually gratuitous. It’s shown all right, the blood and bones and everything, but it’s clearly not real. It’s not even three-dimensional: Obayashi drew the blood in the film. Like with a crayon. Other effects, including ghosts and electrical sparks, are similarly drawn-on and campy. In fact, very little in the film doesn’t feel like part of some weird kindergarten-meets-slasher experiment. In addition to the hand-drawn blood, there are tinted freeze-frames, a painting that vomits blood, and something As the violence escalates, the girls lose further layers of clothing. Hausu!!!!!

I don’t want to spoil the murders for you, but there are only so many ways for a house to skin a cat, or a lingerie-clad schoolgirl, as the case may be. Obayashi had to get creative. The aforementioned pillow fight is between Sweet, one of the girls (she likes sweets), and a haunted linen closet, which barrages and ultimately smothers her with levitating pillows, sheets, and mattresses. The film’s Wikipedia page describes another death: “As Kung Fu lunges into a flying kick, she is eaten by a possessed light fixture.” Luckily though, her legs aren’t gobbled up by the, uh, light fixture, and they continue to pummel the walls of the house of their own accord. Bodiless body parts are rampant in the film: in addition to Kung Fu’s legs, Mac’s decapitated head flies around and bites Fantasy’s butt, and Melody’s handless fingers dance out a tune on the piano keys.

As with any film of this ilk—shitty but awesome—there is a question of the filmmaker’s intent. Did he really want it to come out like this? Was he making a statement of some kind? Is he just really, really bad? Tommy Wiseau, the man behind The Room, claims his film, often called the worst ever made, came out as he intended it. Hausu, recently inducted into the Criterion Collection, spawns a similar debate. Did Obayashi know what he was doing? The whole film gives the impression of a man with one shot at making movies just throwing everything possible into the pot. One of my favorite reviews says Obayashi didn’t really go bananas until he literally went bananas, and turned a man into a heap of bananas near the end of the film. I’m not so sure though. I mean it’s crazy, but in a really cool way, and though Obayashi has admitted he didn’t know how all the effects would turn out—and he didn’t storyboard shit—there is a sense of intention. Maybe it’s the Wyeth painting in Gorgeous’s bedroom—the house in Christina’s World looking very foreshadowy—or the consistency of the weird, semi-animation, but I get the sense that there was some method to the madness, that this brilliant whatever-the-fuck-it-is didn’t just happen. Not that it really matters. Some things, like dancing skeletons, are just too good to argue about.

Truly inventive, ever-inimitable, maybe from 1974, Hausu!!!!!!!!!!!

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

This Was Difficult: “Lost in Translation” by James Merrill

by Managing Editor Alec Arceneaux

This is not the sexy kind of poetry that you can say you like on a date to seem sophisticated. And it’s not a poem you’ll probably see in an AP Lit class and dissect for theme and style. It’s pretty long, and has a lot of German and French words, and it’s not very accessible, and the meaning comes out slowly, like sap from a tree. You might not like it. But it’s, well, it’s pretty neat. I don’t know how else to say it. This poem sticks together and asserts itself and quietly does so many things all at once that maybe even Merrill doesn’t realize every little bit.

“Lost in Translation” is, ostensibly, about a little boy (it’s not a stretch to conflate the narrator with the poet; this was meant as a confessional) assembling a jigsaw puzzle with his nanny, though there are vignettes that prevent the poem from being simple narrative. There’s a simple conceit: The puzzle represents the interconnectedness of all things. Pretty basic. But it goes deeper. Merrill is fascinated by words, and how two words in different languages can apply to the same thing. His jumbled and false memories are really just translation. His mind sees the same experience through different lenses, and language is a beautifully incompetent way to express this. In an essay he wrote about the poem, Merrill said, “Words weren’t what they seemed. The mother tongue could inspire both fascination and distrust.”

In the present-day of the poem, as its author is describing the childhood scene, he gets lost trying to remember Rilke’s German translation of a Valery poem, wondering if he hasn’t just imagined it. He’s pained by the thought of Rilke having to abandon the “sun-ripe felicity” of the original French in order to preserve the “monolithic truths” underneath the frame. “Lost in Translation” sets out to capture the feeling that every poet wants to avoid, namely that putting anything into words is doomed to failure at the outset. The puzzle is an unnatural way of fitting unnatural pieces together and hoping that the thin veneer of the image is enough to redeem all that is lost in their representation. Even trying to describe this poem comes out superficial and dumb.

The climax of the poem shifts from long pentametrical verses to Rubaiyat rhyming quatrains describing the fairy-tale picture of the jigsaw puzzle. The fantastical story told there, which pulls in Merrill as a child, is one of the many little metaphors which combine to show how incomplete and unhelpful metaphor is. The poem is a constellation. It’s self-conscious about the ways that it fails, but it makes beautiful art through its failure.

I started and stopped writing this column about three dozen times. (It doesn’t help that I have two papers due tomorrow.) Nothing is harder than knowing how bad of a job you’re doing at portraying something that really affected you. I tried joking, and anecdotes, and candidness, and pleading, and self-deprecation, and even deprecating the poem, but nothing stuck. I hate the stupid irony of not being able to express my love for a poem that’s essentially a love song to the impossibility of expression. Read it, please. Excuse my weakness. “All is translation, and every bit of us is lost in it.”