The Arts Review editorial board reflects on Prince’s legacy.

Alejandra Salazar

One of my mother’s first concert-going experiences was a sold-out Prince arena show in college, sometime in the 80s. Her wistful reminiscing of that night was how I first learned about the legend of the Purple One. Whenever his music would play on the car radio, she’d turn up the volume and glance over at me with this giddy smile on her face and ask, “Ale, do you know who this is?” Six-year-old me would be sitting in the backseat, confused but curious, watching my mother gradually turn into a teenager as she was transported back to that arena, watching history be made. “Ale,” she’d say when the song faded out and she snapped back to reality, “That was the best show I’ve ever seen.”

It’s been around thirty years since the fact, and she’ll still tell you that. She and my father spent nearly twenty of those years instilling in me that same reverence for the artist and his work, filling up my memories with “Purple Rain” and “When Doves Cry” and “Little Red Corvette.” My childhood was a primer in the mythology of popular music. It was by watching my parents’ immediate and inexplicable joy whenever they’d hear the first bars of “1999” or “Kiss” that I saw what good music could mean to people, but I quickly realized that it took a rare, special kind of artist to fully harness that magic. As much of a magician as he was a musician, one such artist was Prince. And he was such a badass, too.

Today, one of my professors took a few minutes to reminisce about Prince in a similar way — wistfully, as if she was recalling a precious memory. She kept trying to contextualize her feelings for us, trying to draw a modern comparison: “This is like — I don’t know, who’s your ‘Prince’?” she’d ask the class, looking around the room for some indication that we understood exactly what the world had lost today. I found the question to be surreal, almost absurd, because the answer was so obvious: my ‘Prince’ was always Prince. There was never anyone else.

Nikki Tran

I wish I’d been born earlier to see this glorious moment unfold live on TV. For who spent ‘95 in diapers or the womb: At that year’s American Music Awards, performers sang “We Are The World” for the song’s 10 year anniversary. Although he infamously declined to work on the original recording, there’s Prince-onstage, adorned in sequined gold, lollipop hanging from lips, shades on low, obviously not singing along. There’s a moment when Quincy Jones points his mic towards Prince, and Prince points back with his sucker. It’s the proto-Kanye-circa-2009-VMAs moment, it’s ripe with dgaf-ness, it’s funny, it’s maybe even childish (according to some on the Prince message board), but Prince didn’t care. He didn’t candy-coat a thing.

If I’m honest, Prince wasn’t in my music repertoire. But if I’m even more honest, Prince underlies most and maybe all of my favorite tracks in the way they make me wanna move, wanna dance, wanna get my freak on. Prince didn’t pave the way for artists today so much as rip up the pavement. I’m sad that it took his death for me to really, truly give a good listen to Prince, but I know I’ll listening for a long while.

Carlos Valladares

Prince was the funkiest, sexist cat on the 80s pop block. MJ and Madonna, brilliant crafters though they were, very rarely demonstrated the yelping, shrieking anxiety that made Prince’s work consistently great and haunting. Prince, like David Bowie (another fateful victim to 2016, the Year the Music Died), assumed multiple identities and was less knowable and harder-to-figure, despite his pop-icon-status. Somehow, you got the feeling that you didn’t need to follow Prince’s exploits as fervently as most pop stars of his day and today. The man shone perfectly through his music. He was perfectly vulnerable—in the stirring coda of “Purple Rain,” in the quiet desperation of “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” in the bold identity ambiguity of “My Name is Prince.”

As we remember His Purpleness, we grieve his loss in the physical realm while assisting his ascension to immortality in the spiritual one. Kick back, relax, listen to Sign ‘O’ The Times, and fall in love with him all over again. That’s what he would have wanted.

Katie Nesser

Much of my childhood was spent pretending to know a lot less about sex than I actually did (public schools in Texas may not have the best formal sexual education, but one can still learn a lot). Whenever anything vaguely adult came up in conversation or on TV, I feigned obliviousness and above all, disinterest. But when Prince played the Super Bowl, I was eleven years old and confronted with the Purple One’s sensual charisma. Prince strutted, flirted with his dancers, and embodied his undeniably sexy music. I couldn’t look away. I can’t have been the only kid squirming that night, sitting next to parents and pretending not to be enthralled by this erotic, charismatic performance. Today, I’m pouring one out for the Purple One. May his soul continue to make family gatherings a little more uncomfortable.

Anthony Milki

There are deeply, deeply special people in the world. There aren’t many, and we usually discover them, and they are gifts that are timeless and that we feel an unusual gratitude towards. We believe they exist in a plane that doesn’t often intersect our own, that their every step is fantastical, and we look up to them and are inspired by them and can’t believe that they can do what they’ve done – and then they’re gone, and the loss resonates painfully but distantly, and we feel their absence because we loved them, we know that now. I don’t know who gets to decide these things. I don’t know how the hell Prince got to be as effortless and comprehensive a virtuoso as he was, or how he never seemed to age or even exist in his own time, or why today was the day he was to be taken away from us. I remember, as many do, watching him at the Super Bowl. I didn’t grow up with Prince, the only song I knew was “Purple Rain,” but he made a middle schooler who only listened to Green Day and the bad U2, who thought rap and Michael Jackson’s crotch-thrust were too vulgar, just sit down and get eaten up by sex and guitars and bounce and emotion; one tiny person couldn’t have caused it all alone. It was all so perfect, he was just so perfect, I didn’t know how to do it justice. I bought the songs on iTunes, I changed my settings so my Finder wallpaper had Prince and that purple symbol guitar. Super Bowl XLI wasn’t a football game, it was a Prince show. I don’t even remember who was playing, it doesn’t matter at all.

We don’t know what killed Prince yet, it’ll probably shock us and sadden us even more in a few days, but we must take solace in the certainty that he went out having the best possible time, and we’ll forever keep bits and pieces of him around and funkifying the airwaves, so that maybe even in our darkest moments we can still smile and have a bit of fun.

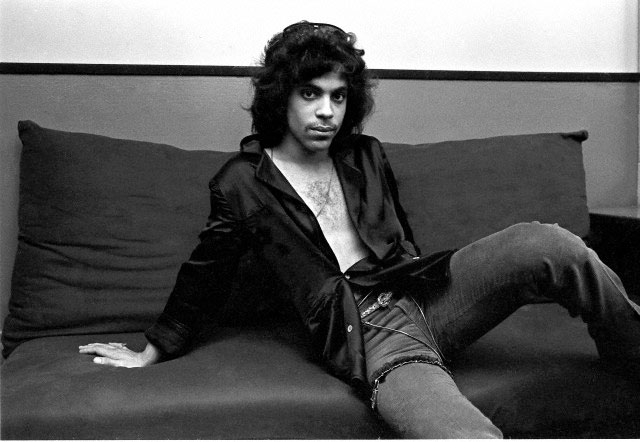

Photo by © Deborah Feingold/Corbis.