A commentary upon the ethics of mass media and the corruption of the American justice system, the touring production of Chicago combines elements of old and new theatre to create a show-stopping spectacle full of lace, sex, and murder.

Set in the Prohibition era of its titular city, Fred Ebb and Bob Fosse’s jewel Chicago centers on the story of Roxie Hart (Bianca Marroquin), a young nightclub singer who murders her lover (Bradley Gibson) as he tries to walk out on her. Roxie is sent to a women’s prison run by the corrupt Matron “Mama” Morton (Roz Ryan), where she meets the famed vaudeville murderess Velma Kelly (Terra MacLeod) and criminal lawyer Billy Flynn (John O’Hurley). She is quickly plunged into the world of mob media and celebrity criminals, unwittingly drowning beneath the flashing camera lights and slowly fading away into coffee stained newspaper pages.

What is particularly striking is the production’s attention to detail and thematic dedication. The entire stage is framed by a literal picture frame, and the way it is staged is so outrageously dramatic that it is obvious that the entire show is just something to look at, with little attempt at realism. During Jacob Keith Watson’s “Mr. Cellophane,” the staging reflects the unnoticeable nature of Amos, Roxie’s frumpy husband; even the chorus member seated at the opposite end of the stage turns her back towards him, ignoring his performance. Watson’s Amos is as pitiful and gullible as he can be, but it’s his vocal power that truly takes the audience by surprise. Amos’s “Mr. Cellophane” is smoothly performed with vocals as sweet and clear as the cellophane he claims to be, a stark contrast to the guttural raspiness of the deceitful jazz he is surrounded with.

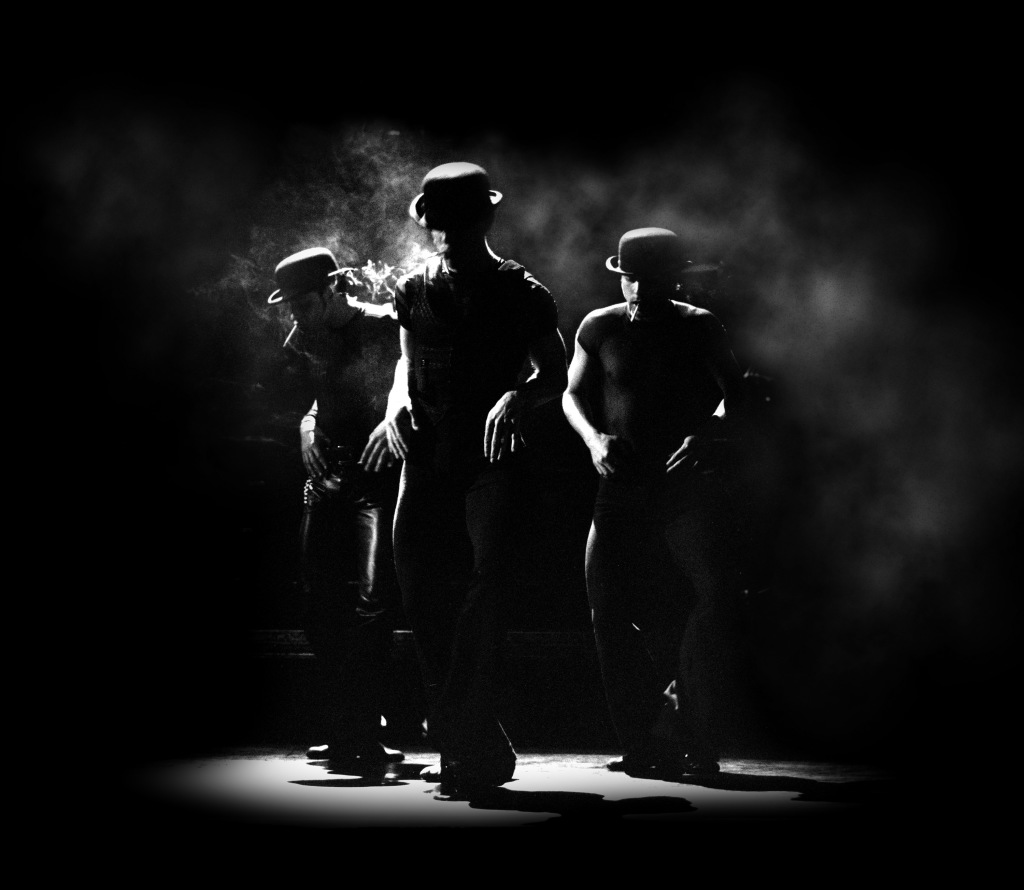

The set is simply a few chairs and some glitter; most of it is the orchestra. Traditional character costumes are nonexistent except in the form of Amos’s dumpy cardigan and straggling tie; nearly everyone else is clad in fishnets, lingerie, and skintight silk, all black, creating their characters through the power of acting.

Clad in sleek black dresses, leading ladies Bianca Marroquin and Terra MacLeod play their characters not only as striking contrasts to one another, but as examples of the progression of time, bringing a sense of unity to the production’s whirling vaudeville spectacle.

Marroquin presents Roxie as a naïve, yet definitely not innocent, twisted ingénue who is both compliant and deceptive; she brings an air of sultry awareness that is lost upon the sweet blondes we normally associate the role with. Her comedic timing is impeccable, although the comedic moment can cause her to be long winded. She gives the audience a break from the painted façade of the show by alternating between overt dramatics in front of snapping cameras and intimate asides with the conductor of the orchestra (Robert Billig), giving a depth to Roxie that can be forgotten in the whirlwind world of Chicago.

MacLeod’s Velma is the sultry goddess we expect to see, her personality shining through her slyly raised eyebrows and sensually pursed lips. The way she slinks about the stage, her smooth, low voice entrancing those around her, is characteristic of the vengeful vaudeville queen Velma truly is. Vocally, MacLeod and Marroquin are powerhouses; the rough, raspy tones of the jazz tunes and the sweet, smoothness of the more introspective pieces are captured wonderfully by the versatility of their voices alone.

The show stays true to the signature Bob Fosse style of choreography, undoubtedly one of the most jaw-dropping aspects of its production. The smooth, slinky, sensual slides across the darkened stage juxtaposed with fast, sharp, clean pops of movement is signature to Fosse’s style; the final song of the show, “Hot Honey Rag,” is beautifully recreated with his original choreography. Velma and Roxie’s story satisfying duet is executed with utmost precision, pops and slinks aside. Yet Marroquin and MacLeod are far from the only spectacular dancers in the cast; nearly every single performer is fantastically impressive in their stamina, grace, and rhythm.

While many of the chorus members are fairly lacking in their acting, Hunyak the Hungarian (Aurore Joly) is the exception, even when the only line we can understand of hers is “not guilty.” Hunyak is the only character in the show who seems to be telling the truth about the nature of her crimes, the only true innocent, yet she is sentenced to be hung while the rest of the cast sings and dances and deceives their way to freedom. Her anguished cries and wide-eyed despair stops the show cold in the middle of its inherent chaos, and her power as a character gives way to explaining the true theme of justice hidden beneath the loud, shiny veneer of the celebrity criminal.

Roz Ryan’s Mama is every bit of stylized corruption channeled into the form of one prison matron; her uncharacteristic laziness quickly changes into action because of her eagerness to make a quick buck. Ryan’s comedic timing is impeccable, and her voice is outstanding; from grating jazz lows to her sultry belt, Ryan never once falters in her character for the sake of her singing, and never falters in her singing for the sake of her character.

The absence of justice, glorification of the wrong idols, and the corruption of the media dictated society we live is brought together by the absence of color in the world of Chicago. Not only are the costumes black, but nearly everything else is black, dark, faded. The American flag that appears during Roxie’s trial is so faded that the colors look grey, a commentary on the corruption of the justice system. Bright lights appear when the media arrives, but they are as momentary and feeble as the fame brought upon by a camera’s flash. Black is the color of corruption, soiling, impurity; absolutely fitting for the nature of this show. Brightly colored lights and glitter do appear a few times over the course of the production, but they are merely touches of disappearing “razzle dazzle” determined to shield us from dirty reality, but only for a fleeting moment.

Chicago is at once satirical and serious, masking its precision and letting just enough of its message poke its head through the dark currents overhead. It’s not simply about vaudeville and murder; Chicago is a tale of corruption, insincerity, and, most prominently, a tale of rank injustice rising from the fumes left behind by the cigarettes of the blind masses.

***

Chicago runs Nov. 7 - Nov. 16 at the SHN Orpheum Theater in San Francisco.

Photo credit 1: Catherine Ashmore

Photo credit 2 & 3: Jeremy Daniel