The Cantor’s new special exhibit, “Showing Off: Identity and Display in Asian Costume,” provides viewers with a sampling of the Asian continent’s rich heritage of textile and dress. Open until May 23, 2016, the exhibit features clothing items and personal accessories from the Cantor’s own collections.

“Asian costume,” in broad terms, recalls several thousand years of cultural, social, and economic history across the Asian continent and all its iterations of nationhood—the dynasties of China, the villages of Vietnam, the nomadic bands of Mongolia. It’s no small feat, then, to encapsulate the whole of these histories in a single exhibit—nay, a single room, in the case of “Showing Off.”

In its limited space, “Showing Off” pares down the expanse of Asian history to a manageable window of time (the eighteenth century to the present) and collection of countries (China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Tibet). Guest Curator Asia Chiao ‘15 drew her selections from the Cantor’s existing collections.

“There was a dialogue between what was available and what I wanted to tell,” Chiao said. In making her selections, she explored the crosstalk that existed among Asian countries-too often, Chiao explained, the cultural and geographical East are lumped together to serve as a counterpoint to “the West.” In reality, there’s a kaleidoscope of disparate countries and cultures at play.

For the reasons of space and ambition of premise, “Showing Off” sacrifices depth for breadth in its examination of costume (a broad, broad word) in Asia past and slightly-less-past. Among the costume items chosen are long robes, head wraps, hats, and shoes; they’ve been stitched, embroidered, cobbled together, and etched in silk, cotton, elm bark fiber. Together, these items provide a sort of impression of a costuming heritage that might easily occupy a dozen rooms or an entire wing of a larger museum.

“Showing Off” is, in this sense, an abstract for a larger statement about Asian costuming. Chiao has made maximal use of a limited space: the result is a compression of culture, couture, and history.

Animals as status symbols are a common thread across all five countries. “The crane on the insignia badge of a first-rank Chinese civil official also appears on the ceremonial apron of a Korean minister,” Chiao writes in her guest curator’s statement. “These similarities testify to the frequent cross-pollination of ideas and technologies throughout Asia over the course of centuries, highlighting the interconnectedness of these diverse regions.”

Another motif among the items on display is a near-oxymoronic desire for both humility and pride—you can toot your own horn if you’ll do so reluctantly, retiringly. This dynamic is captured in a Korean courtier’s apron (the ceremonial apron mentioned by Chiao). Like nearly all garments intended to be worn in court, the apron is ornately embroidered. Clouds and cranes—symbols of high rank—decorate this particular smock. In an ultimate triumph of humblebrag over humility, the designs stitched into the back panel of the garment were intended to be visible even as the wearer was bowing to a superior in court.

The exhibit ends in the early nineteen hundreds, as the Qing dynasty in China was in decline and European tourists flocked to the cities on vacation. The culture of Asian textiles, previously hermetically sealed to external influence, begins to show evidence of cultural crosstalk:

- A jade snuffbox appears in a 19th century portrait of a Manchu court official—the item, introduced by Jesuit missionaries, quickly became a status symbol. In reclaiming the snuffbox for an Asian context, some Manchurian artists chose to render it in jade, a quintessentially “Asian” stone.

- A series of portraits of a Japanese woman ends with an image of her seated at a desk in a European dress and what appears to be a corset. The title of the piece is “Planning an Overseas Trip,” and an image of vaguely European buildings looms, indistinct, in a cloud over the woman’s head.

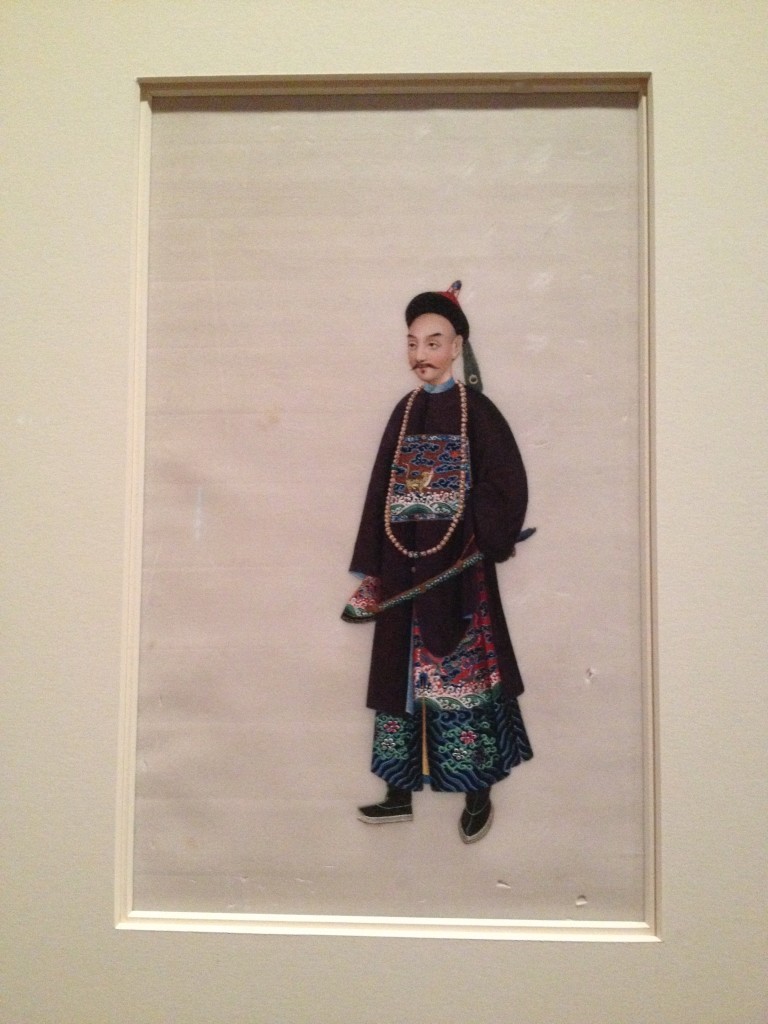

- An 1850 souvenir portrait of a courtier from the Court of the Imperial Guard in China features Western-style shading. The courtier’s lone figure appears against a background of plain white, a traditional Chinese technique.

Increasingly, Asian identity and display become a melding of Asian and European identities as the exhibit draws closer to the present day. Chiao doesn’t make explicit mention of this in her curator’s statement because she intended a focus on Asian cross-culturalism. “That’s a whole ‘nother exhibition,” says Chiao of the blurring of boundaries between East and West. Asia remains the focus of “Showing Off,” even as an impulse towards globalization makes itself known.