I don’t feel 100% qualified to write this article.

Though the mention of Darren Wilson and other badge-wearing criminals makes my blood boil, I am nevertheless a beneficiary of a fucked-up legal system and militarized police force trained to service white lives while devaluing and eliminating black ones, and no amount of regret or rage on my part will cause a cop to look at me in the same way that he or she would look at a boy like Michael Brown.

This doesn’t mean that I should stop feeling this intense regret or participating in marches; but it should be made clear, to myself and other white allies, that feeling sick to the stomach with shame and disgust when a cop car turns the corner is not the same as feeling afraid for your life. By writing this, I don’t want to appear to be claiming a sorrow that is not mine, or, in the words of this article, cannibalizing the movement. If you want to read excellent articles on the topic of Ferguson and police militarization, look here and here and here, to start. There is no shortage of eloquent, well-informed articles making their rounds on the Internet right now that deserve to be read far more than this.

***

As culture and commentary editor, I’ve been asked to reflect on the role of art in protest movements, specifically the movement sweeping America right now with regards to Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and the literally countless other black lives taken by the American “justice” system. What can art do for and in the face of systemic racial violence and police militarization?

My gut instinct is to say not much.

But perhaps I am not looking at things from the proper perspective. Perhaps I need to force myself out of myself, I who have access to the hair-raising articles listed above and a campus full of dedicated activists, and instead try to see things through the reprehensible eyes of those who don’t care. Because, for all my liberal politics and claims to the contrary, it isn’t that hard to put myself in their shoes. It is these people, mostly white, that this article will aim to address. How can I reach these people, the privileged majority for whom the good cop/bad cop dichotomy still feels relevant, whose children dial 911 without a moment’s hesitation? While I believe that art doesn’t truly have a place on the front lines of a political movement, this certainly doesn’t mean that I think it is meaningless as a political tool. Rather, I believe that art’s most resonant, impactful place is before and after political action: preceding and following the turmoil as a contained form of turmoil in of itself.

At a protest, you march, you chant, you are a body at the service of a cause or injustice far bigger than yourself. Art, the oh-so-personal, would be a distraction in these moments of solidarity and mass action. For me and my own art practice, it would be frankly arrogant to assume that I have anything to say during a protest against the non-indictment of Darren Wilson: as an ally, you are there to listen and offer your body up to the cause, as a number, a tool, a symbol of resistance against the existing justice system. Your individuality is put on pause; you are there to express the exact same thing as the ally standing next to you, which is, yet another citizen standing up, registering his or her disgust with the police force and his or her solidarity with the cause. You are, quite simply, saying NO. No more racist police. No more black lives lost. No more blind acceptance of an irreparably skewed system. This is the script and you are there to follow it; to deviate, even under the guise of creative expression, would be the deepest disrespect and moreover, a gross manipulation of white privilege.

The places where one should be talking and creating, which is to say, producing art, are the spaces typically unreachable by activism-those private zones of complacency or apathy, offices or classrooms or lobbies or bedrooms, where life goes back to “normal.” Art is most impactful in two instances: for the moments after political action, to keep one from getting too comfortable, to check one once he or she sinks into the couch, and for the many people who, let’s face it, will never leave their couches to join this cause, who can’t or won’t or don’t want to. Perhaps counter-intuitively it is these people, snug in their homes with ample down time, that art should target. Art, historically the domain of the bourgeoisie, is a political tool in plush disguise. It can bring home the message born of rallies, and force a private reconciling by getting underneath the skin, into the bloodstream, as readily as that Xanax can.

Let me scale back for a second. Drawing from my own experience in the world of queer and feminist politics, I know the strange and sudden impact of a boy boarding the subway in a crop top or platform heels. Business as usual, a boring commute, is rendered suddenly volatile by this deviant midriff. I know the electricity that zings through the train-car when a girl takes off her coat to reveal a NSFW skirt. Sex peeks through business-as-usual, and beyond that, violence, discoloring the farthermost corners of one’s daily routine. A question hangs in the trapped air of the train-car: will business-as-usual be upheld? These moments, not immediately political but teetering on the brink between ho-hum and horrific, bursting with radical potential despite their everyday setting, are art’s municipality.

“Why not just be normal?” worried parents ask their lipsticked son, a sentiment echoed by puzzled patrons of a piece of art like Piss Christ. The other day I actually heard a man grumble, “Black kids wouldn’t have this problem if they just stayed inside and wore normal clothes.” Apparently, he considered house arrest run-of-the-mill but baggy jeans abnormal. Why not just be normal, one asks? Simply put, because our current version of normal is fucked.

To be clear: I am not trying to take the spotlight away from the issue at hand, the targeting of black bodies by police, or equate my own experiences with the daily trauma of being in black in America. I am only trying to use my personal history to understand how to approach so complex and dire a dilemma, and how to present this dilemma to the cozy masses who refuse to see how it could possibly concern them. What does concern them is the all-holy notion of normalcy, of “good” taste and “safe” streets, of Yelp reviews (because that is democracy) and family vacations, of police who come promptly when called. What gets their attention is not systemic injustice, but far subtler breaches of conduct, like underwear visible over the top of one’s pants: small-scale negations of one’s worldview, pesky holes which art can transfigure into The Abyss. There are too many people who can’t imagine another way of living; it is the artist’s job to imagine this better or different world for them, to offer up a new spin on existence that would have otherwise been unthinkable.

I have thought about what I hope will come of all the articles being circulated online and the protest marches springing up all over the nation. Will the justice system be re-formed? Will the men who murdered Michael Brown and Eric Garner be adequately punished? I would like, against the odds, to say I hope so. However, what the current political action most immediately boils down to, in my very insignificant opinion, is a reconsideration of what is normal. And this is no small task. The protestors’ focus on highly publicized traditions like the Macy’s Day Parade and the NYC tree-lighting is an extremely interesting tactic. When interviewed, onlookers were outraged that their tradition had been tampered with, not cancelled or ruined but merely altered by the pesky influx of protestors before the police ushered them away. “How dare they,” people cried—in this instance, not about the murder of an unarmed black teenager, but about the interruption of Christmas caroling.

What America needs, and can do right now, is to re-evaluate its romanticization of tradition, which is to say, all that is engrained and taken for “the way things are.” The Macy’s Day Parade is a tradition. So too is racial violence. So too is a broken justice system, to quote this article. Something art can do quite effectively is push home the point: traditions are not inherently sacred. Just because something has been repeated over time does not make it infallible-in many cases, this makes it the most suspect. When UVA, a college currently on the hot-seat or its disgustingly negligent yet all-too-common campus rape procedures, was ordered to change the sexist lyrics of its fight song (praising girls who “take it up the rear”) a petition went around calling it an “integral part” of UVA student life, and their oldest a cappella group is still allowed to sing it in its original form.

With a re-evaluation of what is generally accepted as sacred comes a re-evaluation of what is normal. At this very moment in time, it is normal for a cop to kill an unarmed black person and not be legally punished. At one time not so long ago, it was normal to see lynched black bodies swinging from trees. Art derives its power and much of its leeway from its position as the “anti-normal:” it is a disruption, an alternative to business-as-usual, an object or event that produces an emotive experience elevated or removed from the banality of daily life. It can be a distraction from daily life because it is so beautiful, or so ambitious, or because it somehow contradicts the accepted notion of What Is-whatever the adjective, it is mentally preceded by the adverb “unusually.” It is an 80-foot butt plug in Paris, a college student carrying a mattress on her back, the devastating calm when Billie Holiday utters, without a hint of irony, strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

People rally because they are outraged, and people riot because, in the wise words of Jay Smooth, they have reached their human limits. Art doesn’t need to be present at rallies or marches to stir people up; it needs to be present in the spaces and moments where people are apt to forget their rage, to let it go in favor of normalcy. We forget that What Is needn’t be. Cops target and kill black bodies for many equally corrupt reasons: because we as a society have been trained to devalue black lives and because the police have been trained to associate blackness with criminality—but all of this also happens, or is allowed to happen over and over again, for the simpler, more pernicious reason that we as a culture see this as “the way things are.” Police militarization is accepted, a sad fact of life, like the inevitability of rape. Alas, alas, we sigh. What a wild word. These world-weary utterances make us forget that it is this way only because we allow it to be.

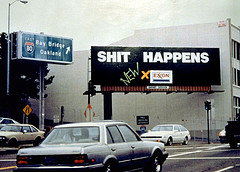

Art’s task, then, is to make the acceptable unacceptable. If not in terms of policy, then at least personally-the private realm of one’s opinions and emotions is, after all, art’s playground and landing-strip. Perhaps this sounds simple, painfully self-evident, but stock phrases ranging from shit happens to c’est la vie impart the depressing truth of our familiarity with violence. Yes, shit happens, but that doesn’t mean you have to swallow it. Just as a tradition is not necessarily holy because of its repeatability, neither is a shitty thing inevitable because of how often it occurs. We have grown familiar with injustice, like a neighborhood stray, and now we let it run free, shitting all over the lawn, just because it has a collar.

Art should prompt a constant process of re-evaluation and should by definition pose a threat to tradition, that which we accept as sacred and unchangeable, due us by the fates that be. Our only birthright is flexibility. Art is an aggressive mirror that tells you just how fat, or afraid, you are. It is a brutal Post-It note, a semi-frequent visitor who tracks mud and wets the bed. Why is a black boy in a hoodie or a commuter’s high hemline considered outrageous, sending a stir through the train station, but trigger-happy policemen allowed to walk free? Certain things need to be re-thunk. Art has the rare ability to make people second-guess not only the traditions they consider inviolable or the things they take for granted, but themselves and their actions as well.

A recent thought-provoking performance by Willing Participant, a theatre group that “whips up urgent poetic responses to crazy shit that happens,” put this notion to the test. The concept for their performance was simple: people of all races walked up to policemen in Times Square and asked where they could find “some peace and quiet.” The unusual simplicity of this request, and the cops’ overwhelming eagerness to help, prompted participants to rethink the “normal” association of a policeman with an Ubermensch or murderer, forcing both cop and civilian to second-guess their knee-jerk assumptions. What if Darren Wilson had second-guessed his deeply racist urge to shoot? A moment of pause might’ve made a world of difference.

In short, we need a new normal. We need a remix of “the way it is.” As black-clad bodies chain-link across the Interstate, facing the horns and headlights of stalled traffic, the rallying cry to be heard is: no more business as usual. Art, in a softer yet no less staunch voice, riffs on this statement by asking, what’s so good about the usual anyway? Think a while before answering.

Photo 1 by Lucas Oliver Oswald

Photo 2 by Nick Salazar

Photo 3: Piss Christ by Andres Serrano (1987)

Photo 4 by Milton Rand Kalman