On Sunday afternoon of Parents Weekend, I found myself sitting in the backseat of a rented Toyota RAV4, listening to my parents debate whether there had been more snow in Boston this year or last. I tried to look it up on my phone, but we still didn’t have service, as we entered hour two of our drive back from Yosemite. The debate raged on, with both sides bringing very nuanced arguments about the frequency of snowblower use into the mix.

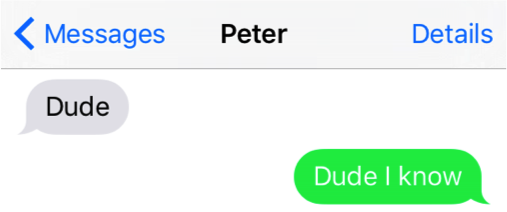

As we crossed the mountains and our cellphones managed to snatch the tiniest bit of EDGE network in Groveland, CA, I read the following email sent to me and my friend, Peter:

![]()

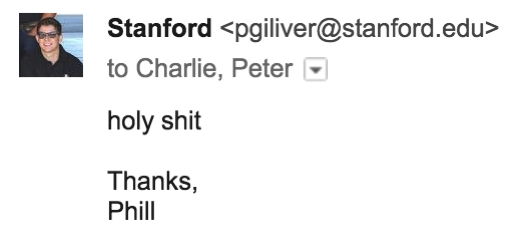

A few seconds later, I received a text message from Peter, and I eloquently responded:

A minute later, I sent back a carefully worded response:

I started to freak out. I had less than a week to prepare, and it suddenly dawned on me that every single stand up joke I’ve ever written or performed never was (nor will be) funny. I canceled my extracurricular commitments for the week. I tried to get an extension on a paper. That job interview I had? Postponed. I was opening for Demetri Martin, goddammit, and in my idiot head that meant that I didn’t need a career.

~*~

You know that thing in the mid-2000s where you would accidentally buy a movie or album on iTunes? And then every single time you were on a long car ride (to Yosemite, for instance) that would be the only source of entertainment? And then, years later, through some sort of Stockholm Syndrome conditioning, you realized that you actually loved that movie or album? Perhaps it reminded you of those family vacations you would take, or perhaps you had grown to appreciate the hidden details in each song or scene. In any case, it was a formative piece of art in your upbringing, and no matter how hard you tried, you would never escape your subconscious love for accidental-purchases like National Treasure 2: Book of Secrets (a movie that I will defend to my death, and also one that unexpectedly appeared on my parents’ credit card statement in 2007).

But among the many regrettable iTunes purchases that I made (RV, Van Helsing, Now That’s What I Call Music 18) in the pre-Recession era of excesses, there was one that I never had to force myself to enjoy. From the very first moment you start playing Demetri Martin’s These Are Jokes, you realize that this isn’t a normal stand up comedy album. Instead of having a hype man at the top of the show, Martin’s album starts with the soft crackling of a vinyl record and his Greek grandmother saying, “Hello, I’m Demetri’s grandma. And, uh, I welcome you all, and I hope you like this CD we made.” Then there’s a minute of dissonant music. Then the comedy starts.

Demetri Martin acknowledges and embraces his esotericism, and his stand up reflects that. Martin’s style is to deconstruct and reconstruct stand up comedy. To see this, just look at the tracklist on his first album: “Some Jokes,” “Other Jokes,” “These Jokes,” “Some Other Jokes,” “The Jokes With Guitar.” He goes out of his way to reject not only the frilly pageantry of his contemporaries, but also the baseline comedic process. And once he’s finished deconstructing, he reassembles his jokes into crisper, sharper, and ultimately better versions of themselves. Why not try bringing a notepad with a bunch of graphs on stage? Or why not try playing the harmonica, guitar, and xylophone while telling jokes?

For most comics, the style of Martin’s “bits” (a word comedians throw around that describes anything that we are trying to make funny) is not worth pursuing. Martin’s jokes are intricate, eccentric, and perfectly calibrated, which means that if they’re not performed just right, they’ll fall flat for most crowds. So when you’re starting out as a low-level open-micer, performing stand up in the back of a Redwood City coffee shop for literally one person (an experience I went through not-too-long ago), it’s difficult to go out on a limb and suddenly whip out the oversized notepad filled with nuanced wordplay. No, instead, you talk about hokey bullshit like election season or your mother-in-law. And if you keep doing that, you’ll develop a style that may persist through the rest of your stand up career. So the fact that Demetri Martin’s peculiar brand of humor survived and thrived in such an unsupportive environment is a not-so-minor miracle.

~*~

A few hours after Peter and I received that email, we found ourselves driving towards Brainwash Café, a full-time comedy club and also full-time laundromat, in the SoMa district of San Francisco. As we drove, we both tried to work out the wording on some new jokes. Peter was trying to make a joke about the redundancy of “cookies-n’-cream ice cream” work; I was figuring out how to make a joke about the origins of the phrase “the proof is in the pudding.” We’re very high-brow comics, I’ll have you know.

Every once in awhile, in between reciting our jokes aloud or scribbling down premises, we’d pause and audibly exclaim, “This is ridiculous.” The other would agree. Then we would realize that we were actually opening for Demetri Martin and would let out a string of disbelief at each other: “This is insane.” “It’s pretty stupid that we’re allowed to do this.” “How is this real?” “Why do we get to do this?” “I’m so fucking excited.” “Me too.” Then we’d pause, calm down, and repeat.

That night, I tried my performing the set I would be using on Saturday, picking out some old jokes I used to close with, and peppering in some new ones as well. There were maybe 15 people in the café, with six listening. Halfway through my set, a man in the crowd walked over to the front row, right in front of the stage, and started licking a table. I asked him how it tasted. “Bad,” he said. Great, I thought. If, when I was opening for Demetri, there were going to be tables in the front row and a man started licking one of them, I now had a quick go-to quip. These open mics were definitely paying off.

Tuesday, we went to Kell’s, a bar with a basement-mic that smelled like a due-for-demolition YMCA. I happened to be the only comic who brought a backpack into the show, thinking that I could make some headway on some homework while waiting for my turn. The host, a flannel-and-horn-rimmed-glasses-wearing-cool-guy that I had never met before, introduced me as “a real comedian,” which is a thing hosts do when they’re not sure if a new comic will ruin everyone’s mood, evening, and life. The open mic, which resembled a sparsely attended high school party, was already dying out by the time I went up, but the few edits that I incorporated into my set got good laughs. Even though I knew I was getting limited stage time in the week leading up to the show, I felt like I was making progress.

At Kell’s, talking about the Magic School Bus shrinking and juicing its occupants.

Wednesday, I did some of my homework and rewrote my set.

Thursday, I did an updated and cleaner version of my set back at Brainwash. The jokes were coming more consistently, and, as I listened back to the recording of my set, I was learning the beats, the pauses, the phrasing, the physical gestures, and the small details that elicited even the slightest giggle. I was happy with where my set was at that moment, knowing that in between classes I hadn’t been getting as much stage time as I should have. Every second that I was performing counted, and every giggle was a datapoint.

Friday night, Peter and I performed at our weekly open mic at CoHo. At this point, I had my “final” set and was just doing a few dry runs before the show the following night. I went up, and it was like I was back in that coffee shop in Redwood City performing for nobody. Time slowed. For 6 minutes, I fidgeted my way through my “best” material, over the sound of grinding coffee beans and an elderly man coughing into his corduroy shirtsleeve. “Thanks, that’s my time,” I lamented.

Right after bombing, I went to another mic on campus, hoping to gather some semblance of self-confidence before calling it a night. Hey, you know what’s worse than bombing once in a night? Doing it two times in a night. And you know what’s worse than bombing two times in a night? Bombing two times in a night with a set you’re supposed to perform in front of Demetri Martin.

~*~

“I just realized that this literally doesn’t matter to anyone but us,” Peter uttered as we ordered sushi a few hours before the show. “The audience probably doesn’t care, and Demetri definitely doesn’t care.” The sentiment cut deep, and I knew that he was right, but that didn’t stop me from having a minor panic attack as I waited for my tuna roll. “But at least these shirts are a good bit,” I responded, pointing to our matching shirts that I had made for the occasion later that night. From the sound of my voice, it was clear that I had felt a lot more confident two days before, before I had been asked “Demetri Who?” as I lifted a warm t-shirt with Demetri Martin’s face off a vinyl press.

As we drove back to campus two hours before we were supposed to be at the venue, we could both feel the adrenaline starting to kick in, as though we were living through a lamer version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. We decided to give ourselves a half hour to ourselves: Peter watched an episode of Louie in his room; I sat and stared at a wall for 27 minutes.

We arrived at the venue an hour and half before the doors would open for the public and were greeted at the door by a smiling young lady named Trista. “Hey guys, thanks again so much for doing this,” she said, as though we were the ones doing a favor for Demetri Martin. “The green room’s right over here.”

“Trista, did you get my rider?” I joked. Trista paused, concerned, and mentally ran through the massive checklist of things she had to do to prepare for this event. “I’m joking,” I said, knowing that she must have thought I was serious. I had somehow managed to have one of my bits bomb before I had even started my set, which is a new personal best (or personal worst, as the case may be).

We were led to the green room, which was not green, where there were Demetri’s requested tangerines and tiny water bottles, evidently a diet for comedians. Peter and I were to wait in this room, and Demetri would get his own personal room. We would, however, be sharing the same bathroom, which I felt was an honor and a privilege.

For the next hour, the most mundane activities suddenly became exhilarating just because Demetri Martin was marginally associated with them: “Oh, I’m peeling a tangerine and drinking water out of a tiny water bottle that Demetri Martin personally requested.” “Check it out, they’re bringing a strawberry salad into that room…for Demetri Martin.” “Oh, I have to lock the door to the bathroom so Demetri Martin doesn’t see me peeing because I drank too many of those tiny waters…that Demetri Martin requested.”

Every 19 seconds, I would check the clock, making sure that time had been passing. We paced up and down the tiny room, weaving between couches, drinking tiny water bottles, occasionally pausing to sit down and dread. Then we’d laugh, remembering our mantra of “this doesn’t matter to anyone but us,” and continue pacing around the room as adrenaline slowly trickled into our bloodstreams. “The shirts were a good idea,” I said.

At 9:20PM, ten minutes before we were supposed to go on, a walking stereotype of a show producer with clipboard-in-hand and headset-on-ear called us over. “Hey, do you guys mind going out cold? With, like, no introduction?” Peter, who was going first, didn’t mind. “Alright cool, in that case I’ll give you a heads up when you’re good to go,” Mr. Producer announced.

A few minutes later, the lights in the corridor darkened, which meant that the house lights had gone down. Mr. Producer walked over, and gave us the thumbs up. Peter got up, walked down the hallway, and ambled onto the stage. As I sat in the green room, panicking about my set, worrying about the wording on one of my newer jokes, mentally running through my failed past performances, thinking back to the time a heckler tried to fight me because he hated my set so much, remembering the time that I bombed following a ventriloquist comic who had been wearing a bandana over his mouth, and thinking over all the times that people told me that I’m not funny, that I’m trying too hard, that I won’t ever be able to be a comic, that I should give up, give up, give up already…

I heard the applause. Except, unlike the other times that I’ve performed, this applause kept swelling louder and louder, with a stronger energy than I’ve ever heard from a crowd. It’s the difference between stepping into a puddle and being caught in a tidal wave, so when Peter let out his first joke and 600 people simultaneously let loose their laughter, all my energy turned from nervousness to excitement. In seven minutes, that’s going to be me, I thought. Was I sweating through my shirt — I had not sweat through my shirt — Was I thirsty — NO, I wasn’t thirsty — where’s my joke list — there it is — should I walk around this couch six times — I should walk around this couch.

While I was pacing back and forth in the green room, caught in my own fanciful comedy world, Demetri had left his personal room and was wandering around backstage. I turned around, suddenly face to face with the man whose albums I had listened to dozens of times over, whose poster I still have hanging in my room at my parents’ house, and whose entire style of comedy had defined my sense of humor.

“Hey,” he said. “Hi,” I responded. In my head, though, I was screaming “DON’T DISTRACT ME, DEMETRI. I’M IN THE ZONE AND I NEED TO DO A GOOD JOB OPENING FOR YOU.” We exchanged a few awkward head nods, and then I went back to my brooding. On stage, I heard Peter starting his second-to-last joke, so I shuffled towards the hallway leading to the stage. From behind me, I heard Demetri say, “Good luck out there, man.”

~*~

When I walked out into the spotlight, shook Peter’s hand, and took the microphone from the stand, I remember pausing a second to take in the experience. I looked around and smiled, making sure that people could see the joke I had written on my shirt. As I did so, a kid in the front row looked at my white sneakers and shouted, “Damn Daniel,” like the phrase, from the meme on the Internet. I thought back to the man licking the table in Brainwash cafe, and stared the kid down for a moment. “Shut the hell up,” I said. That got my first big laugh of the night.

I don’t really remember the rest of my set from that night. At a certain point, autopilot kicks in, and (if you’re well prepared) you subconsciously rattle off jokes that you’ve polished over time.

The only other thing that I specifically remember is that the laughter had a larger inertia to it; I would say a joke, and then it would take a little bit longer than usual for it to hit the crowd, diffusing through hundreds of audience members. Then, I’d wait for the laughter to die down, but it would keep going. It was the easiest crowd I’ve ever performed for, where I was literally cutting off the audience’s laughter to get in another joke.

I finished my set. “Thanks, my name’s Phill, and that’s my time,” I yelled as the audience got louder and louder. I put the microphone back, walked off stage, and freaked out in the green room. Peter and I hugged each other. It was genuinely one of the happiest moments of my life.

~*~

And then Demetri Martin went up and crushed it — no, annihilated it. I want to say that it was a return to form, but that’s not true because he had never lost it. He’s still in his comedic prime, and he consistently hits his audience with a punchline that’s four or five steps ahead of everyone in the room. He’s still the hyper clever writer-guitarist-sketch-artist-comedian who inspired me to try doing stand up for the first time. He’s still mind-blowingly hilarious.

But he’s more than that. At a meet-and-greet after the show, it became clear that Demetri Martin is one of the most self-driven people in comedy. He’s written tens of thousands of jokes in dozens of notebooks throughout the years, and if he wants to reference something, that’s no longer difficult because he came up with a Dewey-Decimal-style system to keep track of everything. He famously taught himself to write ambidextrously because he thought it would be fun. He once wrote a 500 word palindrome just because.

It was at this point that I finally understood what sets Demetri Martin apart from most comedians. Martin’s comedic “bits” are purposefully weird and difficult, but this doesn’t dissuade him. He is never going to take the easy route to a kitschy punchline because it would be too easy; someone’s already done it.

I think this is partially because Martin honed his craft in a pre-Internet New York City, where avant-garde comedy was encouraged and widespread. When he was starting out, there was never a rush to post the latest half-baked quip to Twitter or, as the “Damn Daniel” dipshit in the crowd brilliantly demonstrated, regurgitate non-humor that others thought of first. If a bit bombed, that was the end of it, and you confidently moved on.

Demetri told us about a few choice moments from his early days. Apparently, one night at one of the more popular open mics, Nick Swardson, another comic, convinced 50 or so people to pretend that they’re all part of the same improv troupe. Then they all came up on stage at the same time and “did a scene,” yelling and shouting over each other for 5 minutes. And that was Nick Swardson’s set for the night.

A different time, Demetri Martin went to an open mic and decided to eat a cookie every time one of his jokes didn’t work. The problem, however, was that every time he tried to tell the next joke, he would still be eating the previous cookie. So because he couldn’t enunciate, he just ended up eating a full box of cookies instead of saying his jokes. But that situation is funny, and that’s what mattered.

~*~

Whoever first said, “Don’t meet your idols” must have been an idiot who looked up to unimpressive assholes. You should absolutely meet your idols. You should ask your idols about how they got started, why they got started, and why they keep going. Ask them how they get better. Ask if they’ve ever wanted to quit. Why didn’t they?

Let your idols put your efforts into perspective. Are you working hard enough? Do you truly want to be as good as them?

In the case of Demetri Martin, it was invaluable to see just how much harder he works than most people. He doesn’t get distracted. He doesn’t care if the joke is hard to write, perform, or draw. He’s going to put in the effort, and if it doesn’t work, then oh well.

I’m not saying that hard work is the surefire formula to be a successful comedian, but I am saying that the most successful ones — Jerry Seinfeld, Louis CK, Demetri Martin, and so many others — worked tirelessly to get good at what they love: making people laugh. Over the week leading up to the performance, I got the tiniest taste of they do, and I have to say, I loved it.

~*~

After we had chatted, and after all of the volunteers running the event had left, I packed up my raincoat, joke book, and autographed backstage pass. I looked around the green room where, one-and-a-half hours earlier, I had been panicking about bombing. I started to leave. “Hey,” Demetri said. “Good luck out there….And nice shirt.

Demetri Martin, Peter, and me backstage. I’m glad I put the effort into making the shirts. They were a good bit.