In the past year my friends have all become obsessed with Snapchat, finding it easier to send grainy close-ups of their moles (captioned CANCER?!) than to text me hello. I didn’t get it at first. Why send ugly pictures of boring things with mildly funny captions that disappeared before you got the punchline?

This summer I caved and finally got an iPhone. Near the top of my list was figuring out this Snapchat business, and before too long, just as my friends had warned me, life began to appear to me as an endless series of potential Snaps. Long hours in the office became unduly flowery as I doodled over my everyday life. A burrito wasn’t truly da bomb (as read the caption) until I’d shared with my friends; the boredom of internly duties was made risky, potent, by the lengths I was willing to go to to illustrate my state (like smooshing my face in the Xerox machine and snapping the result).

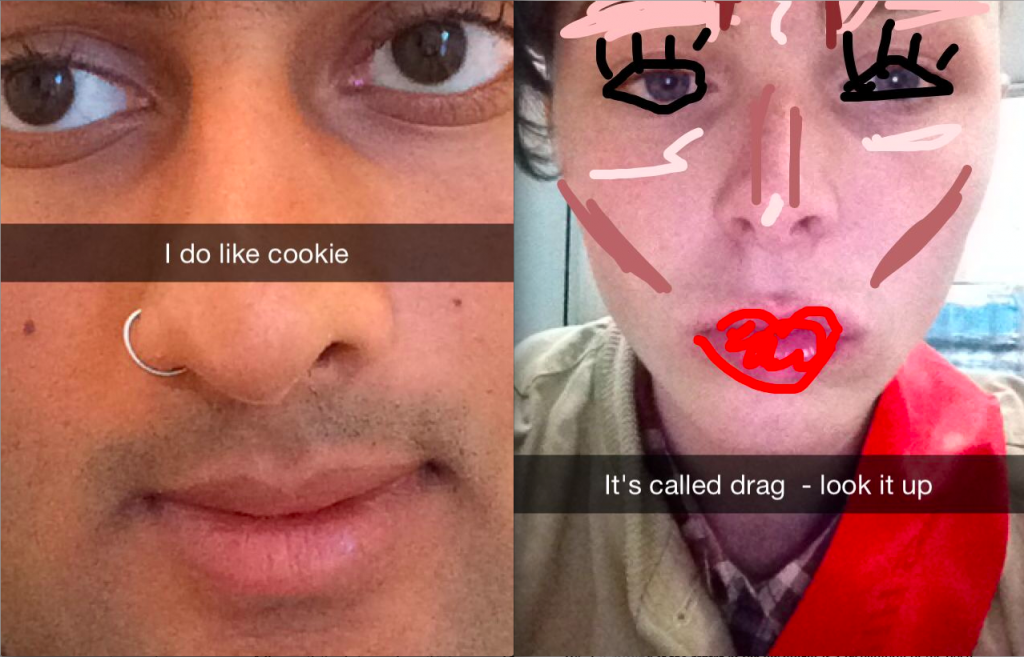

While this obsessive period didn’t last long, it got me to pondering. It seemed that Snapchat appealed to my basest self, the self whose thoughts, when alone in a room, slipped into third-person narration. Snapchat is like the cool-kid equivalent to talking to yourself, in that it validates your existence via a response—even if that response is a blurry photo of a friend, also sitting alone in a room, with an illustrated mustache and the groundbreaking caption i am the king doe. The fun and ephemeral form that a snap takes hides its central invocation (see me); one is not boasting when they send out color-saturated snaps of parties so much as they are begging—see this, see me, confirm that I am real.

Thus, a Snapchat is more than an unflattering selfie: it is a retaliation (however flimsy) against the hypermediation of a modern world that makes you doubt your own reality. It seems telling that the Snapchat mascot is a little ghost, one who feels, just like us, insubstantial; this would make our snaps like hauntings, bumps in the virtual night.

Only in this day and age could an app originally designed for the distribution of nudies become a mini museum, which, quite like a regular museum, caters to the irrelevant and/or unexciting (i.e. my best friend’s daily updates on her dog) and still features its fair share of nudes (thank heavens). Within the special context of Snapchat, the mundane is deemed noteworthy if only for its temporality, for its brief stint in the Now.

So, Snapchat confirms your existence: I am here now. Facebook, social media’s prettier older sister, portrays a slightly zestier one: I was once there, in that club, in Ibiza, in latex. Or, I am the sort of person who would get down in that club, given the chance and the right stimulants. Facebook specializes in the macro and the manicured: it summarizes a life, offering up a grand overview that changes gradually over time. The ability to create and control a projection of myself and to test out differing modes of selfhood (serious prof pic? Lighthearted prof pic? Semi-goth prof pic?) is precisely why I love Facebook, a fact so obvious that it feels ridiculous to explain.

And yet Facebook’s recent “real name” policy, revoked just yesterday, forced us to do just that by suggesting that one’s Facebook persona, or any social media persona for that matter, equals a “real,” i.e. essential and feasible, identity. Facebook’s policy, which the company began enacting a few weeks ago with surprising ferocity, required users’ profiles to show their legal, given names rather than their chosen pseudnoyms. This was a particular blow to drag queens and professional performers, as well as anyone choosing to conceal their legal name for less whimsical, potentially life-threatening reasons—transpeople, runaways, and users with stalkers, dark pasts, homophobic relatives, or abusive spouses come to mind.

My initial response to this policy was a chuckle (because I am a tolerant dad). Anyone who has so much as skimmed the newfeed of your average college student knows that the ever-so-flattering profile pictures and emoji-drenched messages are not scannable fingerprints but socially agreed upon fibs, a collection of blusters that approximate your personage at its best angle. This is the center-of-attention you, not hungover you in the middle of a groundbreaking shit (that’s Snapchat’s terrain). A you that is at once studied and experimental. Social media loosens the restraints on selfhood, makes hypocrisy OK as one hones, through trial and error, a metaphoric self. The Internet, best of all, sidesteps the blunt and often disappointing reality of the body. One’s bloat, elegized by Snapchat, is blotted online. It is not so much an ideal self as a curated self, one’s profile a scrapbook whose large and varied audience demands a merciless editorial eye and, as it turns out, a readiness for censorship.

The most ironic thing about this real-name policy is that for queens, queers, and the tirelessly pomo, their pseudonym (like Lindsay Slowhands or Brigitte Bidet) is actually the closest thing to real in that it acknowledges the limits, fictions, and objective of their digital identities. Of course Lil Hot Mess isn’t her legal name, but neither did you have that much fun at the office party despite the immediately uploaded pix of you grinning and neither did you mean the “let’s do it again!” plus kissy face emoji that you left in the comment section.

If Facebook really is about one’s “real-life” identity, as the officials claimed until recently, then there shouldn’t be an untag option. Your DMV photo should be your prof pic—get ready for the blitzkreig of nonironic double-chins. Do we now need to prove that we are actually laughing-out-loud before we type LOL, instead of the far more common “smiling vaguely to oneself”? We might as well bid ROFL farewell, and make way for the Anatomically Correct Pusheen if authenticity is what Facebook is after.

Drag queens seem to be the only people willing to acknowledge the performativity of not just gender roles but any role, especially the ones we assume online, where our bodies can’t betray us and our histories can’t protest. The artifice of the identities we so strategically craft on social media mirror the artifice of much grander and grislier institutions like gender or class, which is precisely why so many queer people were peeved by the real name policy. Queer people are continuously told not to be themselves, to change or mute their problematic “truths.” Yet now that so many of us have found expression on the Internet (from Xanga to Myspace to Soundcloud to Instagram), Facebook, kingdom of exaggeration, demands that we get real.

If Facebook is hesitant to let us have pseudonyms, the queer experience as Other (with another name, another point-of-view) as well as everyone’s digital experience is invalidated. Fake names make obvious the playfulness and posturing that are the primary appeal to and forte of the Internet. The real name policy seemed to contradict the two most liberating, democratic functions of the Internet: namely, the bodilessness and timelessness of cyberspace. In the total anonymity of kinky chatrooms, confessional Tumblrs, and the dreamscape of Neopets, Ruinscape, and MyScene, my computer-suckled peers and I have post by post, byte by byte, assembled our myriad selves.

Safety, of course, is an urgent reason for not wanting to use one’s real name online. But beyond the question of security, what really riled me were the explanations Facebook used to justify their policy. Zuckerberg is quoted as saying, “You have one identity…Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.” Even the measured and genuine-sounding apology they issued yesterday struck me as a bit fishy when it claimed “the spirit of our policy is that everyone on Facebook uses the authentic name they use in real life.” Once again, FB draws a line between the real and the performative. They want a piece of the physical You. They want to have their (poorly animated) cake and eat it too.

If the digital age has taught me anything, it is that reality is mutable, as is one’s identity. Facebook was the #1 platform for this transformation as my generation learned the art of branding one’s self before it had bloomed, fleeing changing bodies, so wounded by gravity and/or hyper glands, for the fourth dimension of cyberspace. Why, until yesterday, were Zuck and co no longer satisified with the fictionalized identities that their own website enabled? Why do they suddenly want fact, which is to say, flesh? We are all cyborgs now, yet the mastermind himself, ole Zuckerberg, is pretending that we’re lambs. Beautiful gifts from god whose authentic selves must be protected from the very scary hackers who might eavesdrop on our conversations and sell us weight loss pills—gosh, do you know anyone who would stoop so low? First the names, then the flesh. That is what I was afraid of with the real-name policy, and continue to fear with Facebook’s insistence on authenticity.

To be clear, I am a fan of Facebook. I’ve had one since I was twelve, back in the days when untagging wasn’t yet an option and my pubescent shamelessness (or was it very, very misguided vanity?) prevented me from even wanting to untag the high-def close-ups of my unibrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that I in part defined myself by choosing which groups to join (i go out of my way to step on a crunchy autumn leaf, anyone?) and lovingly pruning my Bumper Stickers wall. FB does everything it sets out do and more: it is my news source, my address book, my memory lane, my soapbox, my warped mirror.

But let’s be reasonable. Facebook represents the “real life” Brittany as much as the BlogThings personality quizzes that I obsessively took represent my “true” psychological state—yes, my aura is purple and my anime warrior name is Dusky Temptress. Haven’t the dreadful effects of cyber bullying taught us the dangers of taking anything said or written online at face-value? Bullies feel detached enough to type go kill yourself or no one loves you online, yet the vulnerable people at whom these words are aimed are apt to mistake them for imperatives, for real-life facts. In such cases, it is critical that the fictionality of Facebook and hyperbole of all social media forms be made clear.

Our offhanded attempts at stability via Snapchat have proven that nothing is stable (because every snap disappears), while our studied attempts at personhood via Facebook prove that a person contains nothing if not multitudes (fuck, gotta go hit “like” on the Whitman fanpage.) Regardless of what name I go by, my social media profiles are the conglomeration of not just two identities, as derided by Zuckerberg, but more than I could ever count.

The real name policy has been repealed and an apology issued (major props to the drag community for making this happen) but the question of “realness” still hangs in the air. I have to wonder: how much farther was Facebook willing to go? How much more proof would (or will) they need? Your social security number and father’s middle name? A full-length selfie? A daily Snapchat of my face?

We’ve had a glimpse of what’s on FB’s mind and it is troubling. Will this policy stay silenced, or will the definition of real continued to be specified, warped, and held over our heads until no one, or at least no one I know, can claim authenticity? In which case, I suppose, we’ll keep on snapping pictures of our shit, our genitals, and humble selves, because at least we’re allowed to believe that these things are real (minus the mustache).

Snapchat screenshots courtesy of Charlotte Fox, Nevin Kallepalli, and Finn Love