2015 was one of the more consistently good years for film that I can remember. This is the first time since I started compiling film rosters that I gave out no A+’s and no F’s. The average film was still very solid. Franchises, indies, live action, animation, documentaries, action films–it seemed like every corner of the film world delivered at least one gem I could be passionate about. And that’s an impressive thing for a twelve-month span in a decidedly chaotic industry.

So before we look forward to 2016, let us officially close out 2015 as a year in movies.

As always, two disclaimers: 1) all of this is from what I’ve seen so far, and 2) there are so many movies it pains me to leave off this list. This year, just missing the cut are the emotional mother-son drama Room, Quentin Tarantino’s epically intimate Western The Hateful Eight, Sean Baker’s low-budget screwball social commentary Tangerine, Denis Villenueve’s chillingly crafted thriller Sicario, and the most maddening movie of the year, Adam McKay’s tragicomedy The Big Short. Let’s take a moment of silence.

And now let’s get started!

***

TOP TEN

- Inside Out (dir. Pete Docter & Ronnie Del Carmen)

What makes Inside Out, Pixar’s best movie in five years, both beautiful and infuriating is the same thing—its reductive simplicity. It’s a 94-minute long movie about an 11-year old girl’s mind, deftly following her five major emotions—Joy, Anger, Sadness, Disgust, and Fear—as they experience a life-changing cross-country move. As much as I deeply love this movie, at first it was tough to shake that even a prepubescent girl’s emotional breakdown should be a little bit more complex, and putting even a little thought into how these emotions have emotions themselves proved a surefire way to existentially boil my brain for a few hours.

The kinda brilliant thing about that, though, is that at some point those thoughts go to the wayside and you’re forced to just accept it all. What makes Inside Out infuriating is precisely what makes it beautiful—all of this is complicated and messy, as it should be. Of course poetic and dramatic license needs to be taken to make work a film based on theories from emotional psychology. What Inside Out does astonishingly well—and what makes it vitally important as a kid’s film—is provide a vocabulary to examine and communicate feelings about our own brains, in a way that is fun, insightful, and effective.

What the simplicity of the film also does, however, is allow Pixar to most directly address a question that has been the bedrock of their best films: what does it mean to be alive? The film explores this theme with grace, humor, and deep emotional heft, with pitch perfect characters and unforgettable animation. (Bing Bong makes me tear up just thinking about him.) In Inside Out, to be alive is to adapt to what you can’t change, accept the totality of your emotions, and, to quote an author whose biopic comes later on this list, end up becoming yourself.

- 45 Years (dir. Andrew Haigh)

Andrew Haigh’s first widely-seen film, Weekend from 2011, is an intimate two-hander set over a few days, that used subtlety and deliberate pacing to elicit a surprisingly large emotional wallop. At first glance, his most recent film, the devastating 45 Years, is going for the same thing. However, it’s not that simple—there are, in fact, three characters at play in 45 Years, and for a straight-up drama, it’s one of the most effective ghost stories I’ve ever seen.

Set during the week before Kate and Geoff Mercer’s 45th anniversary party (the oddity of extravagantly celebrating this particular date is acknowledged and a major thematic strain of the story), Haigh’s film follows the way the seemingly-happy couple’s relationship devolves when the body of Geoff’s first love is discovered five decades after she died. Katya’s her name, and she haunts the movie like a specter; every line, action, and delicate emotional shift is all about her. British acting legends Charlotte Rampling and Tom Courtenay play Kate and Geoff, respectively, and beneath every interaction between them is years of unspoken subtext and quiet anguish. The film quickly centers around Kate, and Rampling relishes in playing Kate’s rich uncertainty of how to reconcile the man she loves with the man he has never revealed himself to be, until now.

Simple, captivating, and powerful, this is essential viewing. It’s a haunting story about the intense difficulty of long-term love, about how even the most outwardly stable relationships have weak spots. How could they not, when the parts of ourselves we don’t share with even those we love the most follow us around like ghosts?

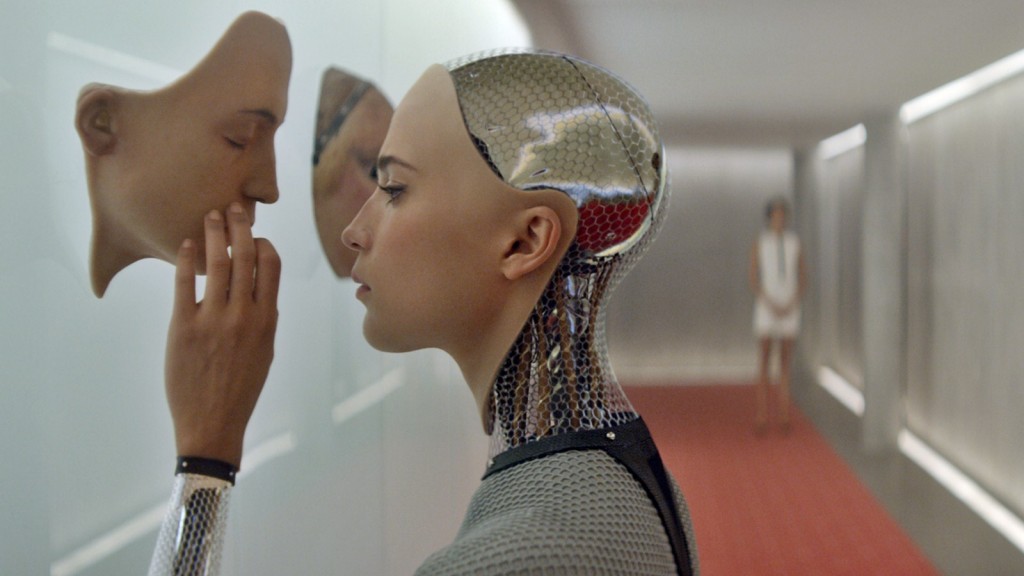

- Ex Machina (dir. Alex Garland)

This mind-bending sci-fi chamber piece is an excellent debut from its director, accomplished screenwriter Alex Garland. For his first film, Garland made the incredibly smart choice to tell a story that is small in practice—there are only three major characters and one central location–but enormous in theory, attempting to use its small scale to encapsulate nothing less than the danger and difficulty of remaining human in a digital age.

It’s a slick, intriguingly written film, but beyond the fascinating ideas at play is the cast, a triplet of actors all at the beginning of immensely exciting careers. Dohmnall Gleeson plays Caleb, an ambitious programmer at a glossy tech company, who is invited to the mysterious remote home of the company’s CEO, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). Gleeson and Isaac also appear together in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, but both have had monster years outside of these films as well. Gleeson found himself in two potential Best Picture nominees, Brooklyn and The Revenant, while Isaac starred in the stellar HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero and shot a role as the titular villain in X-Men: Apocalypse.

In Ex Machina, they play off each other with perfect passively antagonistic banter—all driven by their relationship with Ava, the most advanced artificially intelligent robot ever made, played by Alicia Vikander. (Vikander’s year was also absurd, with her starring in everything from the throwback spy film The Man From U.N.C.L.E to the period drama The Danish Girl.) Nathan, who programmed Ava, has invited Caleb to assess just how intelligent his creation is—and if she could even qualify as human.

From there, to say more would spoil—but safe to say that the movie is tense and fantastic, and that several decades from now, when Gleeson, Isaac, and Vikander are household names, people will look back on it as a gift from the past.

- Son of Saul (dir. László Nemes)

A common doctrine amongst filmmakers is that in the first five minutes of a movie, you teach an audience “how” to watch it—what the movie’s going to be. It’s a concept perfectly illustrated in the prologue to László Nemes’s concentration camp drama Son of Saul, as we follow our main character—Saul, a Sonderkammando, or prisoner forced to work for the guards, played by Geza Rohrig in one of the year’s best performances—lead a group of prisoners off a train, through a room to disrobe, and into a gas chamber. The first thing we notice is the wonky aspect ratio—our frame is a claustrophobic square—and the fact that the entire sequence is shot in extreme close-up on Saul’s face. Everything else is out of focus.

The motive is clear—we are in this man’s experience, his subjective, in-the-moment experience, far removed from any modern narrative about his actions. The technique is carried on for the rest of the film, as we watch Saul claim the corpse of a young boy as his son, and desperately search for a rabbi in the hell of the camp to give the boy a proper Jewish burial. Whether he truly believes this boy is his son, or has finally snapped, or is convinced this is some form of redemption, is never made clear to the audience. The result is eerie—we are stuck in this man’s mind, yet we know almost nothing about it. We are immersed in his world, yet, as everything around him is a blur, are fundamentally removed from it.

In fact, we are so removed that it’s not until additional research is done that the viewer learns that this concentration camp is, indeed, Auschwitz, and that a rebellion that slowly bubbles up around Saul’s narrative is a true historical event. As modern viewers, we know the horrors of Auschwitz, and that any attempt to break out of it is doomed. What Son of Saul does—and what makes it so powerful—is that it takes us away from that knowledge. Instead of focusing on what is historically inevitable, we focus on Saul. We focus on his gaze towards the boy that may or may not be his son. We focus on his impossible determination to bury him right, and, for a second, we forget to ask if any of it even matters.

- Amy (dir. Asif Kapadia)

I went into Amy, one of the best documentaries of the decade thus far, knowing very little about its subject, Amy Winehouse. I knew she was the one who sung that song about rehab, that she had been an easy joke for comedians for years, and that she had died a few years earlier. That was pretty much it.

Kapadia’s film was a revelation to me for a number of reasons. First of all, it is an unbelievably comprehensive biography of Winehouse’s life and her incredible talent, and I definitely consider myself a fan of hers after watching it. Secondly, the fact that it was so comprehensive was eerie to me. The film is comprised entirely of stock footage—some of which came from home videos and recording sessions, but most of which came from paparazzi and prying fans. The fact that there was enough of that footage to comprise an in-depth, two-hour long movie is precisely the point—that her life and death were very much in the public eye.

Lastly, and most importantly, this film is a tragedy. It is structured like one, it is paced like one. We, the audience, watch a promising singer who just wants to create art get so consumed by the celebrity imposed onto her that no one acknowledges there’s a problem. We watch this knowing that not only is there nothing we can do about it, but, even if we had known at the time, there wouldn’t be anything to do about it then. It’s unfortunately cultural, and all we have are filmic obituaries like Kapadia’s that tell a life’s story and make us hope, certainly in vain, that we never see another one like it again.

- The End of the Tour (dir. James Ponsoldt)

The smartest thing James Ponsoldt’s intimate two-hander The End of the Tour does is not make David Foster Wallace its main character. While the late literary giant is the movie’s soul (played with gentleness and love by Jason Segel), the story is told through the eyes of David Lipsky (a perfectly cast Jesse Eisenberg), another emerging writer who interviews Wallace on the final days of the book tour for Wallace’s monolithic bestseller, Infinite Jest. Lipsky just published a book himself that was received with resounding crickets, and his interview seems a thinly veiled quest to try to “figure out” Wallace, to discern what exactly is the greatness in this guy that allowed him to produce a work of genius.

Of course, the answer isn’t that simple, and it becomes clear that Wallace isn’t satisfied or fulfilled in the ways Lipsky expected him to be. This sets up a fascinating dynamic between the two: Lipsky wants to be Wallace, while Wallace doesn’t even want to be Wallace. The film itself is almost entirely composed of the five-day conversation between these two men with very different ideas of their futures - they talk about writing, porn, Alanis Morrisette; they feel each other out and finesse the way they are presenting themselves.

Lipsky’s interview ended up never being published, but he later repurposed it into a 2010 book called Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself. Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Donald Margulies does a stellar job at dramatizing the conversation into a funny and moving screenplay, and Ponsoldt’s objective, realistic gaze helps show the changing relationship between the two men with ease and grace.

At the end of the day, though, the story is about Lipsky, and his slow disillusionment and realization that the man across the table from him is not some mythical figure, but a human with flaws and hopes. Lipsky, and by extension the audience, will never be able to “figure out” Wallace, as much as we will never be able to do the same for anyone else. The best we can do is dive into the work, but there must be a division between the art and the artist. The fallacy of artists is that the work is ever complete, that there is some magical point on the horizon where everything will click and the mind will be whole. The End of the Tour dispels that fallacy, in ways that are as humorous as they are thought-provoking and affecting.

- Steve Jobs (dir. Danny Boyle)

The assertion that director Danny Boyle and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin seem to be making in their out-of-the-box biopic Steve Jobs is simultaneously obvious, heart-breaking, and terrifying—that the technological revolution could only have been driven by people as cocksure and self-centered as its titular tech mogul. The idea of an innovator being a visionary and a one-man-army—an idea that Steve Jobs personified–is still very much an archetype in Silicon Valley, though in the case of Jobs, the amount of iPhones in people’s pockets speaks for itself.

Sorkin’s brilliant screenplay for Steve Jobs doesn’t even get to the iPhone, however, choosing to focus on the high-intensity half-hours before three of Jobs’ earlier product launches. Instead of telling Jobs’ story from cradle to grave and giving us the “greatest hits” of his life, Sorkin molds a blistering character study around the interpersonal relationships in Jobs’ life that followed him around for decades. Sorkin’s cyclical, immensely entertaining dialogue drives the movie, while talented visualist Boyle makes sure the whole thing never feels stagy. Largely, though, the pitch-perfect cast is left to do their own thing, to bounce off of each other in ways that are both operatic and propulsive.

These relationships that Sorkin and Boyle choose to highlight not only cut to the core of the characterization of Jobs the movie presents (Michael Fassbender is in every frame and is excellent, playing Jobs with smarmy and precise intensity), but the core of an industry that is taking over the world. It’s not so much a story about redemption as it is about reconciliation—and not between the characters in the movie, either, though there is that. How do we reconcile the totality of Steve Jobs—this broken, douchey, brilliant man—with the things he created? The technology we make and consume and populate our lives with reflects us–so what kind of people do we want to be?

- Anomalisa (dir. Charlie Kaufman & Duke Johnson)

Who are you?

That’s the central question of Charlie Kaufman’s latest project Anomalisa, which he wrote and co-directed with stop-motion wiz Duke Johnson. It’s a simple question, but one that cascades into increasingly more difficult ones. Who are you really? What makes you special? Will that be the thing that always makes you special? Can you ever really change? Or does the mundanity of life force you to stay the same forever?

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to fully parse Anomalisa’s answers to those questions. This is an extraordinarily dense little film—every frame of it’s brisk 90-minute run time is so jam-packed with depth and symbolism that I’ll certainly be poring over it for years to come. But one thing that immediately struck me was this was it might be the single best, most essential use of animation I’ve ever seen.

Set during a sadly typical 24-hour span in the life of motivational speaker Michael Stone (voiced by David Thewlis), the film shows how his deep unhappiness and existential cynicism has manifested itself in a condition akin to the Fregoli delusion, a world where every man, woman, and child not only looks the same, but sounds the same as well (every single supporting character in the film, male or female, is voiced by character actor and American treasure Tom Noonan). That is, until he meets painfully shy customer service representative Lisa (voiced by Jennifer Jason Leigh), whose voice cuts through the monotony like a ray of light. Their relationship blossoms, even as the audience becomes increasingly aware that these two people are so damaged it’s soon to implode.

And it’s all done with puppets. Only with puppets could inanimate objects that are designed to look alike be as meticulously expressive and distinctive as their human counterparts. Only with puppets could Noonan’s voice be reasonably believed as the voice of everyone else in this world, bringing us directly into Michael’s headspace. Only with puppets could a story about the fears and anxieties of being human be perfectly articulated by that which isn’t even human in the first place. It’s all so layered and intriguing, and by the end, I was so rattled intellectually that it took me a moment to realize how much it had affected me emotionally.

Will we ever know what it all adds up to? Probably not, but it’s a wonderful enough film to warrant digging in to. With Charlie Kaufman, the mystery is the meaning. After all, when he was asked what the film was about, he responded: “…about 90 minutes.”

- Victoria (dir. Sebastian Schipper)

The most sadly underseen movie of the year comes from Germany, where Sebastian Schipper has pulled off a miracle with his film Victoria. Shot all over Berlin, the story follows our eponymous heroine (Laia Costa), a Spanish expatriate running a coffee shop, over the course of one fateful morning as she is befriended by a group of young German locals after a night of partying, persuaded into helping them with a “job” (which ends up being a bank robbery), and then dealing with the fallout. It’s a film that starts off sweet and endearing, and ends thrilling and heart-wrenching.

And that’s not to mention that it’s all done in a single, continuous, unbroken, 2½-hour long shot.

That’s right. It’s a single-shot, real-time heist thriller.

More impressive than the technical feat itself is how quickly you, as a viewer, forget about it. The first forty-five minutes of the film, before the heist conceit is even introduced, is a tender portrayal of budding friendship, eventually focusing on the awkward, sweet, semi-drunken courtship of Victoria and Sonne (Frederick Lau). It’s so lovingly realistic and perfectly grounded (almost all dialogue was improvised) that we are anchored in these characters before the plot even really starts. More importantly, we implicitly know that these actors are not going back to their trailers or getting rest in-between their sometimes exhausting actions. As we, the camera, follow alongside them in real-time, we are in this with them, and they are in this with us.

It’s only appropriate that the first name in the credits, even before Schipper’s, is that of the cinematographer, Sturla Brandth Grøvlen, who was the one holding the camera the whole shoot. His work is astonishing—immersive, delicate, and thrilling, able to convey both fragile emotions and thrilling action beats without missing a step, literally. But his work is just a piece of why this movie is a near-perfect masterpiece—the acting, the scenario, the ending, everything comes together in ways that a film with no cuts should. When the film finally cuts—to black, at the end—there’s a real sense that something profound has happened, that a journey has ended, that everything has changed.

- Mad Max: Fury Road (dir. George Miller)

In 2012, a 70-year-old Australian man wandered into the scorching Namibian desert with an Oscar-winning actress, one of Britain’s most exciting leading men, and the rest of a cast and crew who certainly had no idea what they were in for. In 2015, what they created was finally released, and it’s one of the greatest action movies ever made.

Mad Max: Fury Road is nothing less than a masterclass in filmmaking, and, frankly, I’m astonished it exists. It picks up on a moderately popular franchise from three decades ago, with the only carry-overs being themes and a single character’s name. It brings back the original director George Miller, who has spent the intervening years making almost exclusively Babe and Happy Feet movies. It gives the title character essentially no backstory or lines, has him captured by the bad guys and his iconic car destroyed in the first thirty seconds of the movie, then makes him the sidekick in his own story.

It’s a film with not one, not two, but at least ten badass female characters. It’s a film whose editor had never cut an action film before (and specialized in cutting documentaries), and she was hired exactly because of that. It’s a film where, for no apparent reason, a guy covered head-to-toe in red spandex dangles from a tower of amps on the top of a speeding war rig, playing a flame-throwing electric guitar as battle music. It is all of these things and more.

And–stay with me–isn’t that exactly what movies should be all about? Not Doof Warriors, necessarily, but it is rare for a cinematic world to be feel this complete, this detailed, this lived-in. It’s rare to watch a movie feeling like the universe you are occupying for two hours has always existed and will always exist, and you’re just passing through. For all its fantastical elements, it feels real, and because it feels real, its characters feel real, and because the characters feel real, their emotions feel real.

And because their emotions feel real, we get invested in a two-hour long car chase.

The sheer impressiveness of what Miller accomplished here cannot be overstated. The simple plot of the film—Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) stows away her despotic leader’s six wives and makes for her homeland; Max (Tom Hardy), running from demons of his own, agrees to accompany them–works perfectly, grounding the technical and creative masterpiece happening around it. Using mostly practical effects, Miller has crafted a film that is daring, breathless, imaginative, and joyful, that doesn’t coddle the audience and doesn’t pander.

And because of that, in an industry where movies–especially action movies–tend to be veering towards the most vanilla, safest middle-ground, Mad Max: Fury Road stands out like a diamond in the rough. The movie has been a labor of love for Miller since 1998, and even by that standard it’s remarkable. The work, the thought, the care put into every frame shows, and the audience is rewarded for it.

This film will last. It’s a paragon of what the mainstream film industry—one of the leading creators of our culture—can do on its best day.

***

LINEUPS

BEST PICTURE

- Mad Max: Fury Road

- Victoria

- Anomalisa

- Steve Jobs

- The End of the Tour

- Amy

BEST DIRECTOR

- George Miller, Mad Max: Fury Road

- Sebastian Schipper, Victoria

- Denis Villenueve, Sicario

- Cary Fukunaga, Beasts of No Nation

- László Nemes, Son of Saul

- Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

BEST ACTOR

- Geza Rohrig, Son of Saul

- Jason Segel, The End of the Tour

- Jacob Tremblay, Room

- Michael Fassbender, Steve Jobs

- Jason Bateman, The Gift

- Mark Ruffalo, Infinitely Polar Bear

BEST ACTRESS

- Bel Powley, The Diary of a Teenage Girl

- Laia Costa, Victoria

- Charlotte Rampling, 45 Years

- Brie Larson, Room

- Blythe Danner, I’ll See You In My Dreams

- Mya Taylor, Tangerine

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR

- Harvey Keitel, Youth

- Benicio Del Toro, Sicario

- Mark Rylance, Bridge of Spies

- Oscar Isaac, Ex Machina

- Tom Courtenay, 45 Years

- Liev Schreiber, Spotlight

BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS

- Kate Winslet, Steve Jobs

- Olivia Cooke, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

- Jennifer Jason Leigh, The Hateful Eight

- Marion Cotillard, Macbeth

- Rebecca Ferguson, Mission: Impossible - Rogue Nation

- Elizabeth Banks, Love & Mercy

BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

- Ex Machina, by Alex Garland

- Inside Out, by Pete Docter, Meg LaFauve & Josh Cooley

- Spotlight, by Tom McCarthy & Josh Singer

- Mistress America, by Noah Baumbach & Greta Gerwig

- The Hateful Eight, by Quentin Tarantino

- Tangerine, by Sean Baker & Chris Bergoch

BEST ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

- Steve Jobs, by Aaron Sorkin

- Anomalisa, by Charlie Kaufman

- The End of the Tour, by Donald Margulies

- The Big Short, by Adam McKey and Charles Randolph

- The Diary of a Teenage Girl, by Marielle Heller

- 45 Years, by Andrew Haigh

***

ROSTER

A

- Mad Max: Fury Road

- Victoria

A-

- Anomalisa

- Steve Jobs

- The End of the Tour

- Amy

- Son of Saul

- Ex Machina

- 45 Years

- Inside Out

- The Big Short

B+

- Sicario

- Tangerine

- The Hateful Eight

- Room

- Mustang

- Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

- Spotlight

- The Stanford Prison Experiment

- Slow West

- The Diary of a Teenage Girl

- Mission: Impossible - Rogue Nation

- Mistress America

- Youth

B

- Creed

- Love & Mercy

- Star Wars: Episode VII - The Force Awakens

- The Martian

- The Gift

- The Overnight

- Bridge of Spies

- Beasts of No Nation

- Macbeth

- Man Up

- While We’re Young

- Infinitely Polar Bear

- Mississippi Grind

- I’ll See You In My Dreams

- Carol

- People Places Things

- Spy

- 99 Homes

- Finders Keepers

B-

- Brooklyn

- Dope

- Mr. Holmes

- Faults

- Straight Outta Compton

- Manglehorn

- The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

- Sleeping With Other People

- The Good Dinosaur

C+

- Irrational Man

- Grandma

- Ant-Man

- Black Mass

- Goodnight Mommy

C

- Z for Zachariah

- It Follows

- Kingsman: The Secret Service

- Crimson Peak

- Trumbo

- Results

- Concussion

- The Hallow

- Focus

C-

- The Hunger Games: Mockingjay - Part 2

- Avengers: Age of Ultron

- Southpaw

- Stockholm, Pennsylvania

- The Danish Girl

- Joy

D+

- The Revenant

- Jurassic World

- Trainwreck

- Spongebob: Sponge Out Of Water

D

- Tomorrowland

- Spectre

D-

- The Gunman

***

Photos courtesies or here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.