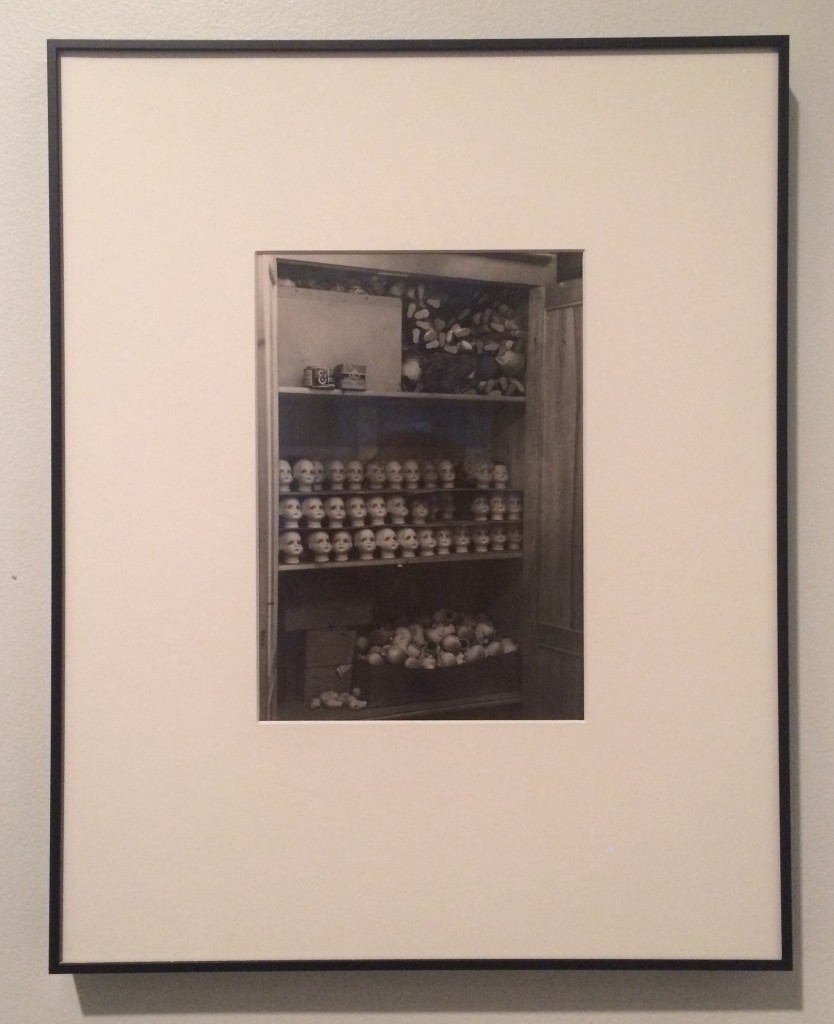

When you first walk into Wanting More at Stanford’s Cantor Art Museum, you are immediately confronted with a quartet of photographs of dismembered mannequins, sharp tools precariously hanging together in a display, and hundreds of liquor bottles lined up and numbered as if test tubes in a lab. Removed from the context of the greater art installation, these images could appear to come straight out of the pages of a dystopian novel, or even out of the scenes of a horror film. Instead, the images are everyday photographs from consumer culture in America.

The exhibition, which opened Wednesday in the museum’s Rowland K. Rebele Gallery, located on the second floor, features the work of photographers such as Robert Frank, Marion Post Wolcott, and Andy Warhol, all of whom used their cameras to critique the spread of consumerism and material culture in the United States throughout the 20th century. By capturing mass-manufactured goods and advertising techniques of the last hundred years, the artists intended to comment on consumerism’s inability to improve or sustain humanity’s quality of life.

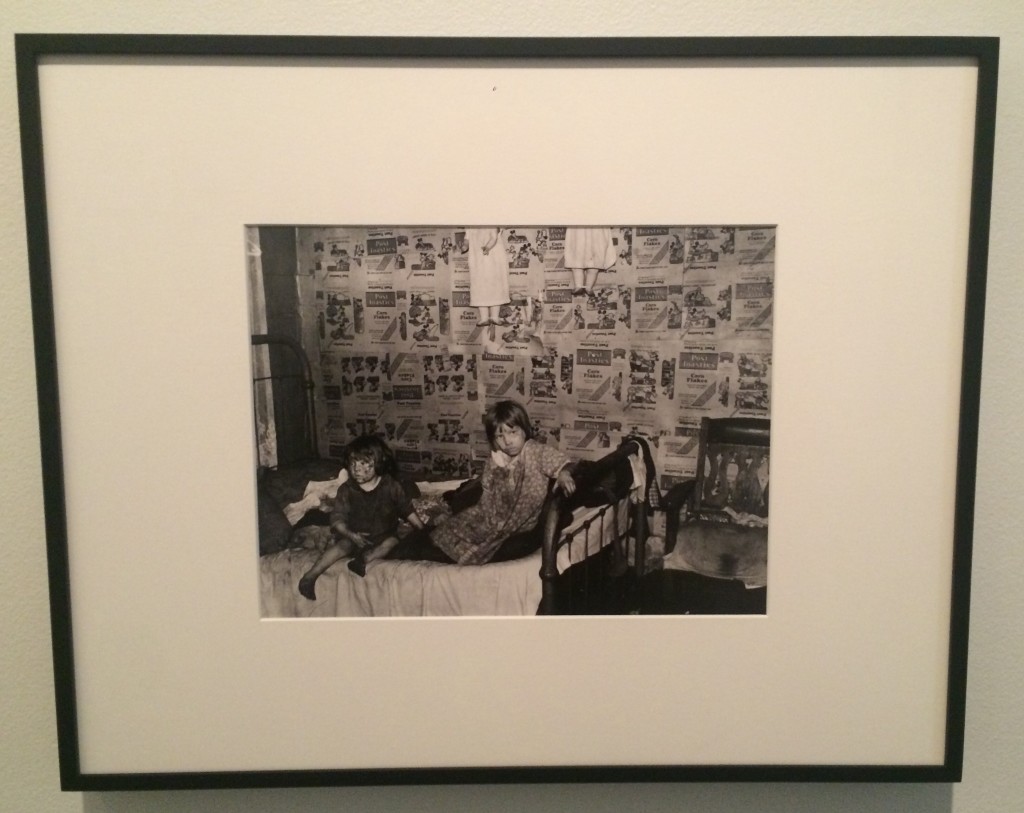

Marion Post Wolcott’s 1938 photograph Coal Miner’s Children On Bed in Their Shack, Charleston, West Virginia demonstrates this sad truth: the “perfect life” that consumer culture promises through advertisements does not exist. The soot covered faces of the young children staring blankly back at the camera stand in sharp contrast with the flurry of advertisements posted on the wall behind them.

What I found most unnerving while attending this show was not the photographs themselves, but the public response. I stopped by the exhibition on the afternoon it opened and stayed in the small gallery of this exhibit for an entire thirty minutes to take it in. While I was there, several other people came through, but mostly out of curiosity to see what the show was about. After they saw that the show was comprised of photographs of everyday items, most people scanned over each work quickly then moved on (one or two asked why there were photographs of milk bottles or billboards up in a museum).

This is not necessarily a positive or negative reaction to the art. It is a normal reaction. The rise of consumer culture and spike in visual advertisement of the twentieth century has left us all somewhat immune to visual images, especially black and white images of common objects (which all of Wanting More’s subjects are). We have become so accustomed to the neon, flashing, catchy visuals of consumer life that we have lost our perception of and appreciation for the quotidian.

Capitalist advertisement culture leaves us Wanting More as consumers, but perhaps this perpetual dissatisfaction and forever yearning for something bigger, better, or more has crept in to our aesthetic and cultural needs as well. Perhaps this is why museum goers, especially those of the young millennial generation, are so attracted to the large, bright, punchy works of the pop art style that so resemble commercial advertisement formats. Perhaps it is this audience specifically that most needs to spend some time in front of the works in Wanting More.

As a member of the MTV generation who has an attention span conditioned for YouTube rather than the Opera, I found myself wondering whether I would have stopped and studied these photos for longer if I had not been there specifically on assignment to write this review. And in the end, I believe that the artists represented in this show would be satisfied if every person who walked into this exhibition left considering these questions — even if they only stayed for thirty seconds to read the show’s name before leaving.