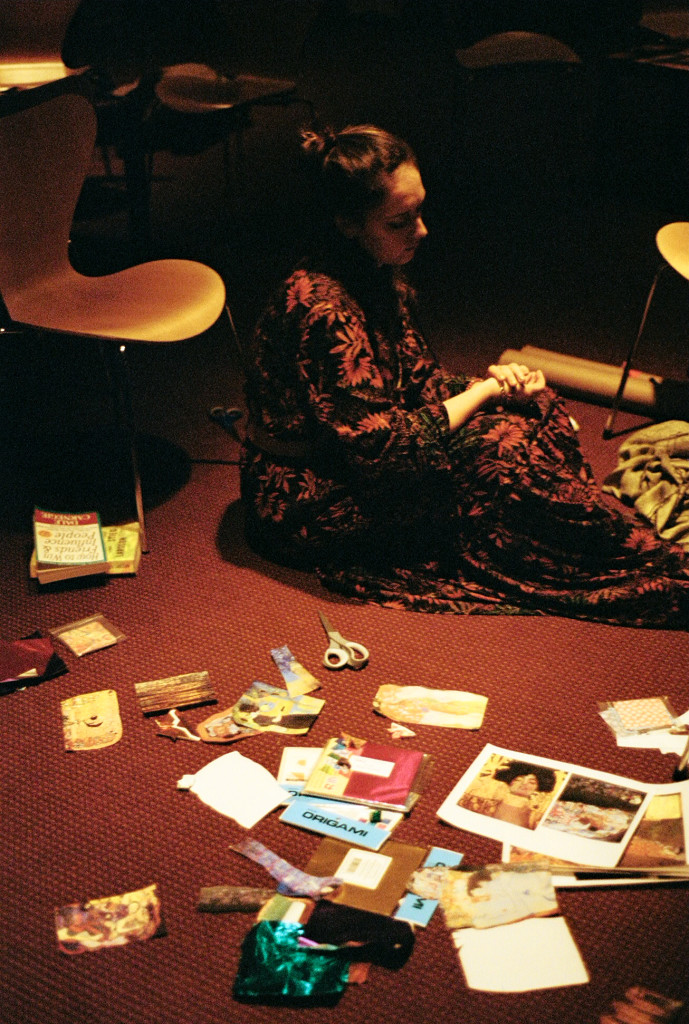

Enter the world of Patty Hamilton’s immersive “The Things That Don’t Translate”, a freeks production performed in New York City this December, through the point of view of contributor Matt Simon.

The woman who greets you at the door has an accent you can’t quite put your finger on – somewhere east of middle Europe, certainly.

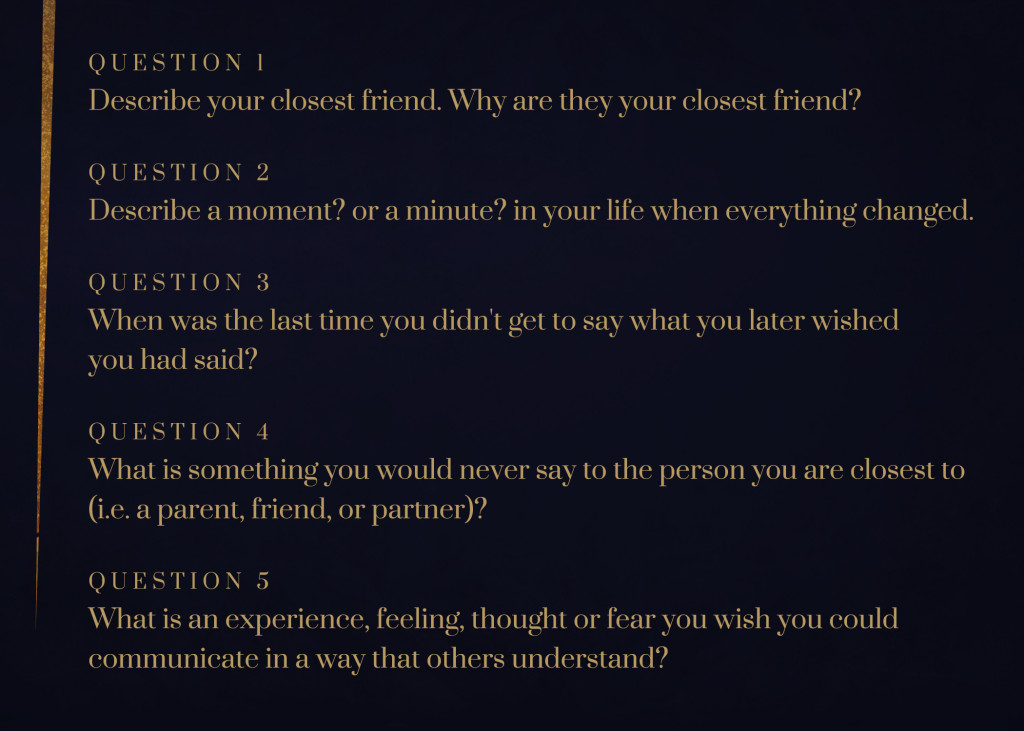

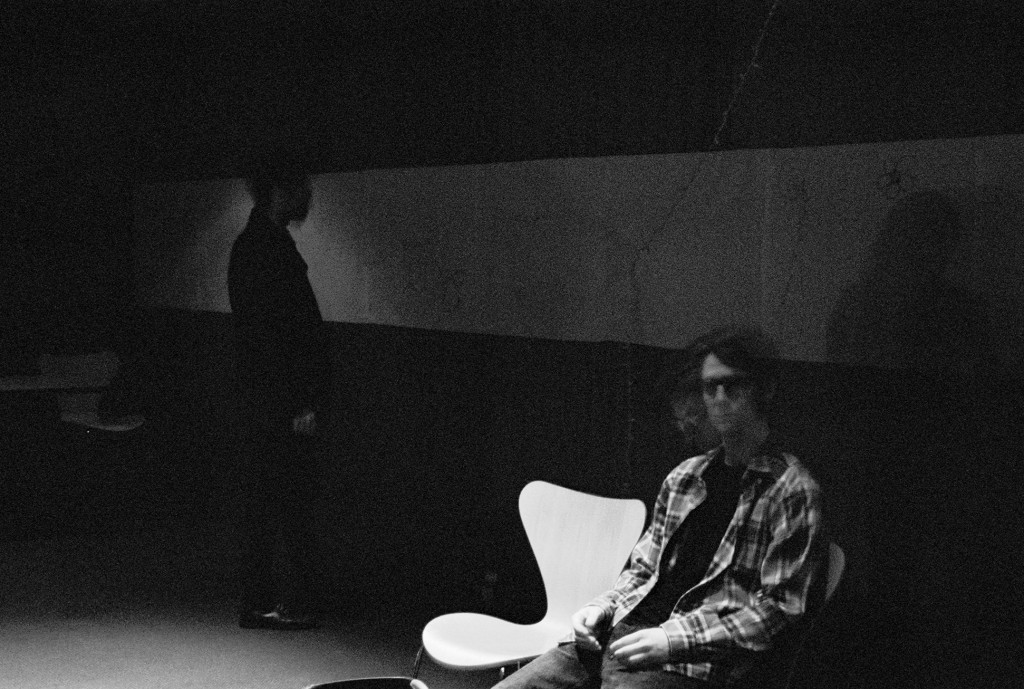

She points out a seat for you, among a handful of other chairs centered around a coffee table. Friends and strangers alike sit at chairs around similar tables throughout the room.

Say your hellos, give your hugs, grab a cup of tea and a brownie that have been so graciously provided, and settle in to The Freek’s New York production of The Things That Don’t Translate.

The play begins and you meet the woman again- her name is Jana and she is Austrian. You’re now observing a scene in Vienna.

Her first revelation to the audience is overtly expository, an explanation of the title and an important clue in understanding the theme of the play: “There is no German word for vulnerability.”

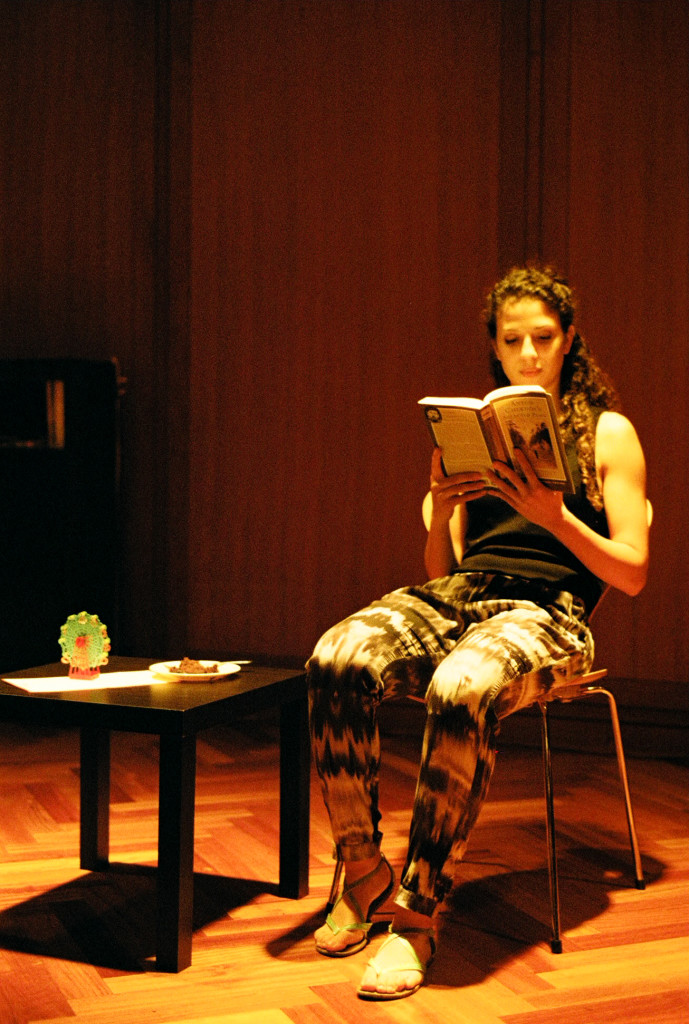

The topic of vulnerability arises from a conversation the Austrian woman Jana, played by Molly O’Brien, and an American traveller seeking her friend, Emma, played by Mariah Leath.

The lights dim on one side and rise on the other side of the room, now the other side of the world. We witness a childhood scene in America between new characters and good friends Mimi and Ben. We watch them banter, joke, and talk about the worlds they know.

But it doesn’t take long to realize that Mimi is Emma, or rather that Mimi gave way to Emma at some point, at some place in her life. You find yourself deeply engaged with this switching sides of the stage and what it represents. You watch as, in parallel, Mimi grows more vulnerable with Ben, and Emma grows more vulnerable with those around her in Austria.

As you watch, you are encouraged to join Mimi and Emma and become more vulnerable with those around you. Jana comes to the stage and asks you to turn to those around you and answer one of five questions from a card in your playbill. You discuss them with strangers, or possibly loved ones. A couple of the characters come and sit among the tables, as well, initiating these rather personal conversations with audience members. Perhaps it’s a bit awkward for you at first – it’s strange to share so much of yourself on a prompt, but you realize that’s kind of the point. Maybe over your shoulder you hear a friend share something you never knew about them, and maybe that makes you want to open up a bit more yourself.

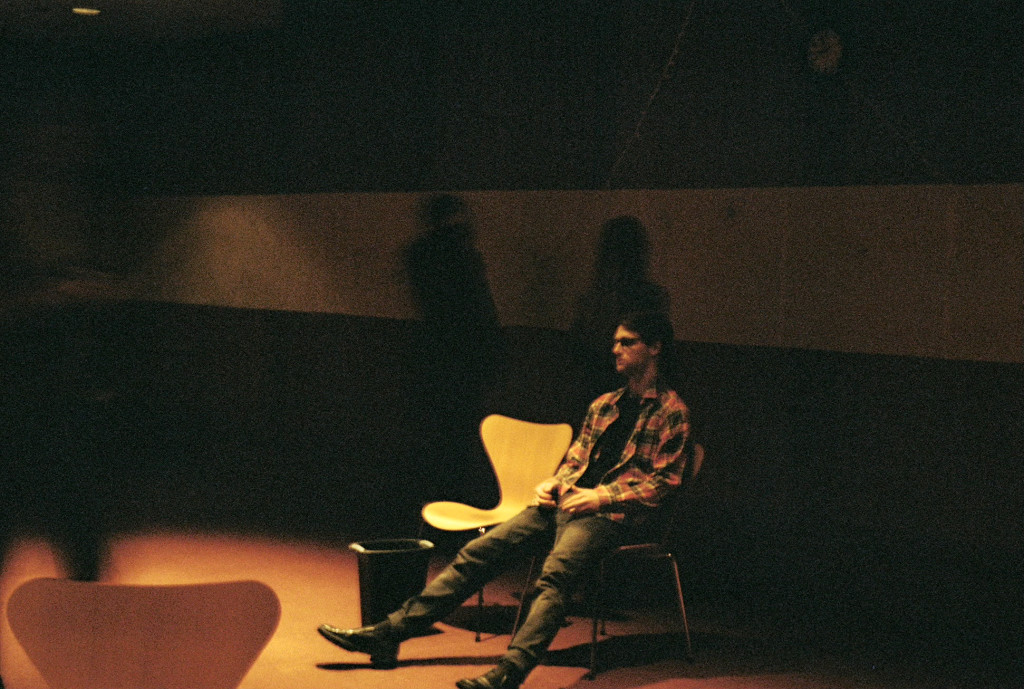

A third world, in some unidentified space halfway between America and Austria, at a table of its own amidst the others, features a conversation between the characters Boy and Girl. Jana is also present at times, trying to moderate as their discussion of morality turns to argument.

How does this stage connect to the others? You sense some confusion and distraction from your friends in the audience, but you’re not bothered by it now.

The content of the argument itself strikes chords in you - both Boy and Girl espouse positions you know you’ve held at one point or another. There’s no such thing as right or wrong, in any objective sense. So what are you supposed to do, just act on some wishy-washy sense of ‘good’?

What implications to their contemplations of objective morality have on the rest of the show?

The whole question is a bit too thrown in your face.

This lack of subtlety in some of the experimental elements of the show is its biggest weakness.

Boy/Girl are too obvious for your tastes – you’d prefer to explore the realm of ethics through some type of allegory.

But there is beauty in the directness. The questions don’t beat around the bush like some fancy metaphor.

They force you to give up the role of passive observer, to think for yourself on the very questions these characters have had to deal with.

And they put you through the same experience that both young Mimi goes through with Ben and older Emma goes through with her Austrian companions, that of sharing bits of yourself.

You at least get a taste of this in these brief interludes when you talk with your fellow audience members.

The show’s strength was in giving us, the audience, a satisfying taste of the world these characters inhabit.

Writer Patty Hamilton has done an excellent job of crafting a script that leaves you hanging on to the dialogue, which is free from flowers and frills.

The story she builds of the relationship between young Mimi and Ben leaves you nostalgic for the simpler days of childhood and anxious about the strains of sustaining friendships.

Director Patty Hamilton (who happens to be the same person as Writer Patty) is also on top of her game.

These characters and all the tensions between them are fully realized through her directorial choices.

Hamilton’s directing prowess comes out best in a scene of movement towards the end of the show.

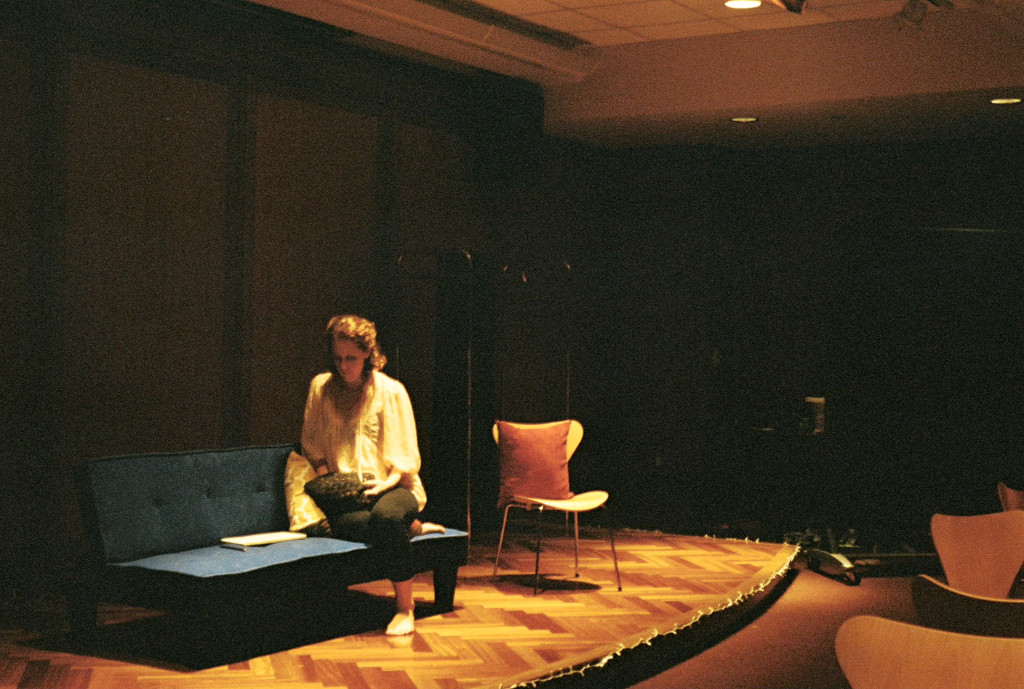

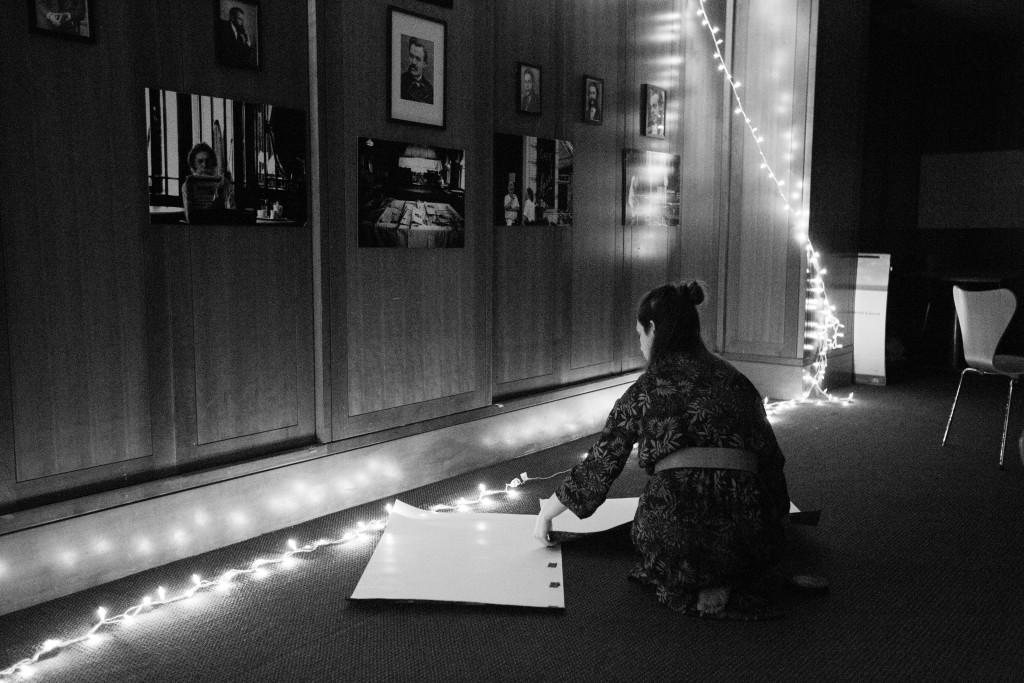

After witnessing these scenes weave together without breaking from their confined stage areas, the female characters break the barriers of the different spaces and enter what feels like a dream.

They change the posters hanging on the walls, move throughout the space, and exchange lines without respect for the boundaries between these distinct worlds.

It’s the only piece of spectacle within the performance, and it is executed perfectly by the cast.

The movement ends. Things resolve back into conversation-more honest conversation, perhaps, than before.

Even without a German word for vulnerability, these characters have found ways to embody it.

Their collisions with each other have opened them up, spilling their insides out for us to observe.

You’ve tried to soak up what they’ve put out there for you.

Have you felt yourself opening as well?

Has the vulnerability of the play translated into your reality?