Susan Rothenberg’s Wishbone at the Anderson Collection

“Pick a side,” my grandfather says.

We are sitting across each other at the dining room table on Thanksgiving. The Y-shaped bone between us is small, and I have so many wishes (to invent a love potion, adopt a bunny, have more friends) I don’t know how to pick.

He tells me to hope for braces, and I run my tongue over my teeth. The next year, I wish them off. Snap. The bone breaks.

* * *

It wasn’t always this way.

In the 16th century, an Ancestor of ours liked himself. The sun fueled his body, a bird circled overhead: she was his oracle, and the bone between her wings a merrythought (later, a “wishbone”). He brought her seeds and she told him when and where to plant them. The bird was never too fat or too frail, and the Ancestor shared willingly with women and children.

And for many years the village flourished.

Until one day, a Stranger arrived. Whether he was born abroad or in the wrong house is unimportant (though they spent years deciding the justification). The point is that the Stranger was one too many. The Ancestor started to count, and the bird on his shoulder squawked—CRAWWEEAAAH!

The end of her life was the start of a new tradition. Over her body, the men in the village flexed their muscles and declared the tug-of-war. Good luck became something to earn, to wrest from the hands of Strangers, sisters and lovers, neighbors and friends.

* * *

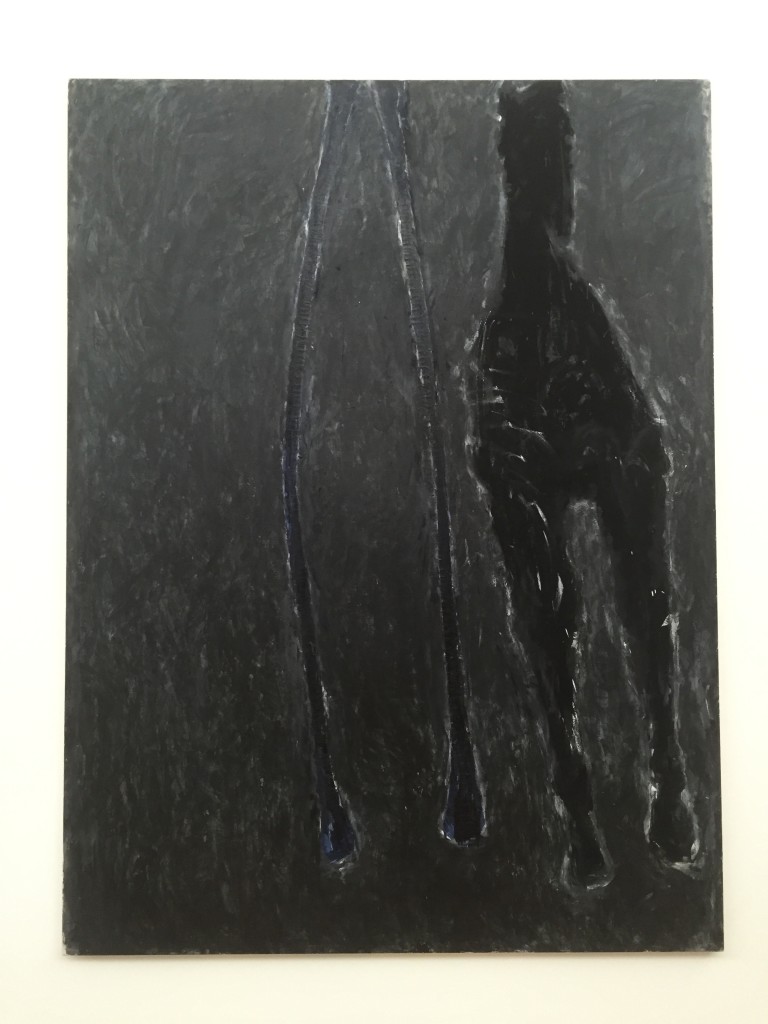

“We are lovers distracted by gain,” Rothenberg tells me. She is a student of the world she inhabits, where there are only two options: to have or have-not. “Wishbone” (1979) exists in the wiggle room between what we have (representation) and what we imagine (abstraction). This bone is stretched out of proportion. Its referent—our if-only’s and big-plans and cannot-live-without’s—is cloudy but its victim is clear. The figure of the bird dangles in mid-air.

* * *

All year long, my grandfather shows me that there are no shortage of socially acceptable reasons to make wishes: a shooting star, for instance, but also a penny heads up; a deep well; a clear fountain; 11:11AM, 11:11PM; a green M&M, a blue one. I wonder if someone is always losing somewhere.

Even on Thanksgiving, a day set aside to appreciate what we already have (at the expense of an entire people), I celebrate the same way I spend my birthday. I close my eyes and make a wish: for the bigger share, for another wish.

Later that night, when the guests are gone and the dishes gathered, I am still reaching into the fridge for second-helpings, bites of butter piecrust and roast turkey and apple stuffing. With straight teeth, I chew and chew at them. Rothenburg’s work, in my head, reminds me. Eat what’s already dead.