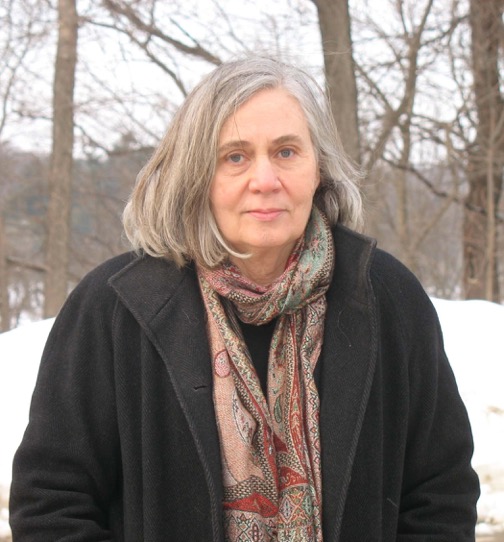

Marilynne Robinson speaks with the raspy elegance of a woman who lives in metaphors. Earlier this month, the bestselling novelist and essayist warmed the audience at her City Arts lecture in the recently restored Nourse Theater in San Francisco. The crowd at Robinson’s interview comprised a mix of middle-aged literary types and, unusually, Calvinists (more on that later). Not belonging to either group, I had come along at the invitation of a friend who, through a friend, vaguely knew the interviewer, Isabel Duffy; we had landed some free tickets. I figured that this lecture would be, like any novelist’s talk, cause for reflection on the craft. But Robinson left me feeling more mortal and less in control than I had expected.

Originally, Marilynne Robinson had set out not to be a novelist but a literary scholar. While writing her dissertation on Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II, she amused herself by writing out metaphors. Wanting to connect with the authors she was reading by emulating their craft, these metaphors were written purely as an intellectual exercise. But, reading over them, she realized they were connecting into a story. The way Robinson told it, the metaphors basically wrote themselves into a Pulitzer Prize nominated, Pen-Hemingway prize-winning first novel entitled Housekeeping. From there, she went on to write novels Gilead, Home, and Lila, as well as several well-received essays.

Emphasizing her characters’ individual voices, Robinson puts her pen to the page and tries to draw what the characters are telling her. This hands-off, modest, nearly deterministic attitude echoes the doctrines of predestination in Robinson’s Calvinist beliefs. Calvinists see humans as less than totally autonomous. Rather than claiming total control over her stories, Robinson speaks as if her characters come to her through an external inspiration.

The idea for her novel Gilead, as she told it on Monday, came to her fully formed. Waiting for her sons to arrive in Provincetown one snowy evening almost twenty years ago, she stared out into the snow. The fictional protagonist John Ames appeared to her with a complete story. She just wrote it down. The book takes the form of a letter from Ames to his young son.

Robinson claims to stand by as a channel through which the characters can speak to this world. It’s like she opens a box entitled “novel” in the morning and spends her days unpacking it onto a page. But Robinson unpacks with care, very slowly. Instead of editing and revising, as most authors are taught to do, she revises each phrase ad infinitum in her head before dropping a perfect sentence on the page. Teasing out each word until it moves with ideal cadence, she lands nearly final drafts on her first go. Duffy, in the interview, marveled how she, a self-described fast reader, lingers on each delicious word when reading Robinson’s work. Unsurprisingly, Robinson also speaks slowly with the lilt of a preacher giving a gently lulling Sunday-morning sermon.

An active member of a church community near her home in Iowa City, where she teaches at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Robinson grapples with big questions regularly. In her classes, as in her novels, she regularly encounters themes like intellect, faith, and mortality. When asked about her lessons for students at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Robinson earnestly discussed the tension between learning and creating in the literary world. She feels that having a brain is the highest human privilege, and marveled at how remarkable it is that we all get to have one. Exercising her brain, and forcing readers to exercise theirs, too, is a priority. She refuses to read anything she finds easy.

That said, whenever Robinson ran the risk of becoming too serious in her interview, she landed a wry comment like, “Oh. Evil. Quite a problem, isn’t it.” This subtle, deadpan wit permeated the talk. One audience member asked formally about her comedy during the Q&A, explaining that her friends often don’t “get” the dark humor in Robinson’s novels. Robinson suggested that perhaps this audience member could find different friends.

As the end of the talk neared, Robinson, age seventy, reflected on the end of her life, too. She does not fear her impending death. Life, this great writer of metaphors explained, plays out in the arc of a story. Stoically, warmly, she’ll guide this story through until the end.