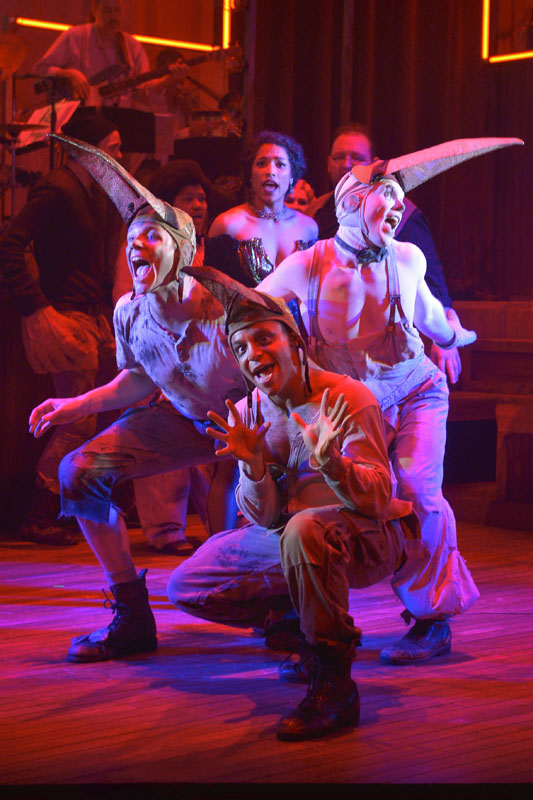

Big Joe (Ian Merrigan) finds his strength—and really big fists—in The Unfortunates, playing at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater through Sunday, April 10. (Background, L-R: Arthur Wise and Eddie Lopez). Photo by Kevin Berne.

The last time a Joe Cocker cover appeared in a musical, young Americans were coping with the horrors of war against the backdrop of Uncle Sam’s demand, “I WANT YOU.” In The Unfortunates, the characters are doing the same, but instead of “Come Together”, the song is “St. James Infirmary Blues.” Made famous by Cocker, Louis Armstrong, and others, “St. James Infirmary Blues” is a British poetic import turned American folk song of unknown origin. And like red, white, and blue flag designs and rock and roll, what is now quintessentially American would not have been possible without a little help from our British friends.

Our similar histories in music and global super-powerdom diverge in the American traditions of blues, gospel, folk, and hip-hop and the non-removable lens of living in the post 9/11 era. The Unfortunates, now playing at the American Conservatory Theater’s Strand Theater in San Francisco, successfully narrows in on uniquely American life while speaking to global experiences in war and death. In this production, which has undergone significant changes under Director Shana Cooper since its acclaimed 2013 premiere at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, “St. James Infirmary Blues” serves as both the story and character inspiration and the name of the hospital where many characters go to die.

(L-R): CJ (Christopher Livingston), Big Joe (Ian Merrigan), and Coughlin (Jon Beavers) face the horrors of war in The Unfortunates, playing at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater through Sunday, April 10. (Background: Ramiz Monsef). Photo by Kevin Berne.

Extrapolations from the song begin with the main character’s name, Big Joe (Ian Merrigan), whose statuesque height and oversized Hellboy fists contrast the way his character shrinks from acceptance and love throughout the show. The performance begins as three friends, Big Joe, CJ (Christopher Livingston), and Coughlin (Jon Beavers), are drunkenly lured into enlisting with promises of glory and Victory Girls. The dancing, flirting, and music thanks to the constant onstage presence of brilliant Music Director Casey Lee Hurt, cut out abruptly as the lights go dark and the three friends drop to their knees with their hands up. Realizing they are at the mercy of the enemy, Coughlin, then CJ, belt out a brief reprise of “I Went Down,” pound their fists, and are shot dead next to Big Joe. Instead of following, Joe pleads for his life and is pistol-whipped into unconsciousness.

According to coverage of The Unfortunates premiere, the show used to begin with prisoners of war crowded in a prison cell, pulled out one by one for execution, until only Big Joe was left. In both versions, the remainder of the show takes the audience on a dreamlike, Godspell-style journey through Joe’s consciousness in the final moments before his death. On one hand, the change in direction at this A.C.T. production led to some confusion-are they dying in the trenches? Are they prisoners? Why isn’t Joe shot immediately? However, it was a crucial improvement in shaping the tone and impression of the rest of the show. Those unclear details ultimately do not matter, considering the surreal nature of the performance. Instead, the audience is left feeling raw and heartbroken as they follow the characters’ journeys from patriotic revelry to violent death and through the stages of grief that occur in a fantastical Americana in the split second between. The innocence and light-heartedness that open this version establish a powerful contrast to the show’s themes.

(L-R standing): Koko (Eddie Lopez), Preacher (Arthur Wise), Madame (Danielle Herbert), Roxy (Lauren Hart), Handsome Carl (Amy Lizardo), and Rae (Taylor Iman Jones) mourn the deaths of CJ (left, Christopher Livingston) and Coughlin (Jon Beavers) in The Unfortunates, playing at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater through Sunday, April 10. Photo by Kevin Berne.

Co-creators Ian Merrigan, Casey Lee Hurt, Ramiz Monsef, and Jon Beavers did not set out to make a political statement. As their lyrics and interviews reiterate, these a cappella groupmates plus Hurt aimed to show that “You can beat death by loving fiercely and connecting with the people around you.” For Big Joe, these people are the carnival versions of those from the real world: the Victory Girl he danced with, turned armless, songbird love interest, his two best friends, turned darkly humorous, death-bringing rooks, the general who recruited him, turned both dangerous gambling rival and manipulative doctor. As Big Joe faces his friends’ deaths at the hands of the metaphorical plague, he continually reacts with anger and denial. In a 90-minute performance, the rapid shifts in mood and plot sometimes prevent emotional believability. Rae (Taylor Iman Jones), whose voice and presence are nothing short of intoxicating, loses some of her depth when she confronts Big Joe. But what is lost in realistic emotion is made up for in repeated musical motifs. Because so many songs and phrasing are reprised, the actors beautifully contrast the different renditions in the emotional weight and style of their singing. This creates the vulnerability and connection that is sometimes lost in the dialogue.

Besides its power to contrast and convey emotions, the music in The Unfortunates is gripping. The incredible live onstage band combines blues, gospel, folk, hip-hop, pop, and spoken word in a way that is both timeless and relatable. The spiritual “Old Time Glory”, with its powerful allusion to “Amazing Grace” , appears after every death but is especially powerful as the cast lowers white-shrouded Rae’s body into a stage trap door. Each of Monsef’s villainous characters is accompanied by rockin’ blues that capture the frantic allure of avoiding death.

Big Joe’s denial creates a wild, creative energy that is mirrored in the set and costumes. From the rooks’ outfits, which range from dusty laborer to sloppy makeup and Cleopatra headdresses, to the Doctor’s stretching, growing red hands that he eventually entangles himself in, to Joe’s (unclenchable!) enormous fists, the production details build a world that is as everyday America as it is dreamy freak show. The lighting is so on point in some moments that it almost distracts from other elements, like the neon Red Cross outline that frames the Doctor or the ashy soft spotlighting in “Catch Me When I Fall.” In a Herculean, Hulkan moment when Big Joe punches the floor in rage, curtains and set pieces fall and turn Joe’s psychological harm into physical destruction.

These production elements would be nothing but a spectacle if not for the unbelievable talent of the cast. Each actor is a vocal powerhouse, which makes ensemble songs almost overwhelming. Livingston and Beavers are the most dynamic and talented actors. Not only are their human characters distinct, believable, and loveable, but their ominous, back-from-the-dead rooks are also fully developed and entrancing. When the two of them are onstage, it’s hard to watch anyone else. But everyone else has standout character moments–Mosef is brilliant, Danielle Herbert is hilarious and powerful as Madame, especially during a bit made solely of drawn out facial expressions, and Arthur Wise is excellent as the Preacher. The entire cast comes together especially well as an ensemble in “Run Joe,” and is diversely talented, always entertaining, and often deeply moving.

(L-R): The Rooks (Jon Beavers, Christopher Livingston, and Eddie Lopez) are out to collect the Dead in The Unfortunates, playing at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater through Sunday, April 10. Photo by Kevin Berne.

The themes and motifs in The Unfortunates are abundantly (and sometimes too) clear–the contrast between aggression and denial and love and acceptance, the necessary stages of grief and, from a literary perspective, the hero cycle the everyman must overcome on his journey, and that how you live while you’re dying should be all about love, joy and music. Though powerful on their own, these themes function uniquely in our post-Afghanistan and Iraq war culture. For many who grew up in that era, war is only something political and senseless. War may just be a mechanism for talking about death, but it is impossible to remove from our collective cultural mind. Thus it is especially challenging to reconcile the current ingrained perspective on war with the message of The Unfortunates–that no matter how useless, cruel, or unexpected death is, we must accept it with grace. The tension of this internal conflict brings The Unfortunates’ thought-provoking matter out of the Strand Theater and into a very real political, cultural, and personal realm. In a generation so defined by terror, senseless war, and political apathy, one man’s pre-death dream world easily and profoundly becomes our real world and leaves an impression that will last for weeks after the curtain closes.