While Keith Haring is best known for his vibrant iconography and his passionate, public battle against AIDS, much of his work lies between these two extremes of joy and despair. Keith Haring: The Political Line, on view until February 16 at the de Young, exposes the lesser known, more somber side of his work. Using the same iconography and aesthetic sensibility, Haring was able to communicate both uninhibited feeling and nuanced political discourse. The show explores his responses to controversial social issues of the 1980s, many of which are still relevant today: racism, homophobia, mass media, poverty, nuclear weaponry, and society’s increasing reliance on technology. The exhibit is organized largely by subject matter, with a few areas dedicated to specific series such as Haring’s iconic subway drawings and his early works on paper and vellum.

While Keith Haring is best known for his vibrant iconography and his passionate, public battle against AIDS, much of his work lies between these two extremes of joy and despair. Keith Haring: The Political Line, on view until February 16 at the de Young, exposes the lesser known, more somber side of his work. Using the same iconography and aesthetic sensibility, Haring was able to communicate both uninhibited feeling and nuanced political discourse. The show explores his responses to controversial social issues of the 1980s, many of which are still relevant today: racism, homophobia, mass media, poverty, nuclear weaponry, and society’s increasing reliance on technology. The exhibit is organized largely by subject matter, with a few areas dedicated to specific series such as Haring’s iconic subway drawings and his early works on paper and vellum.

The subway drawings in particular mark a specific time and place. In the early 80s, Haring created simple (and illegal) chalk drawings on the soft black paper covering expired advertisements in New York subway stations. He drew dynamic figures, often in under a minute, that brought vibrancy and life to the then seedy public transit system. Haring was frequently fined and arrested for these illicit drawings, marking a particularly close encounter with the political and legal system of the day.

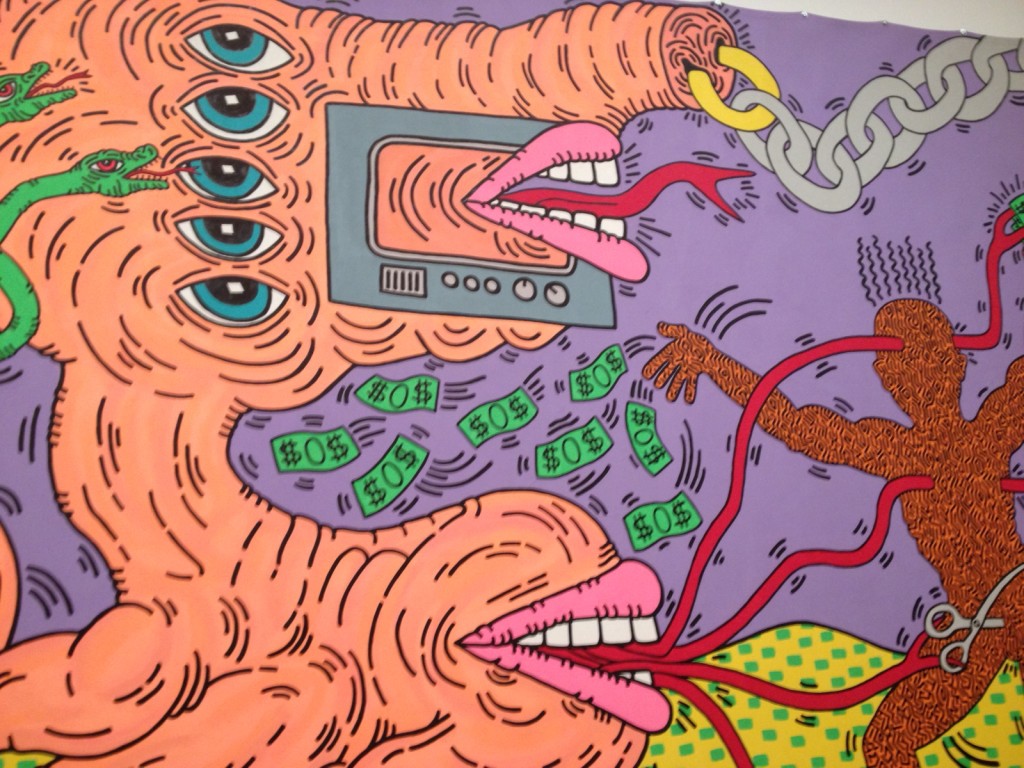

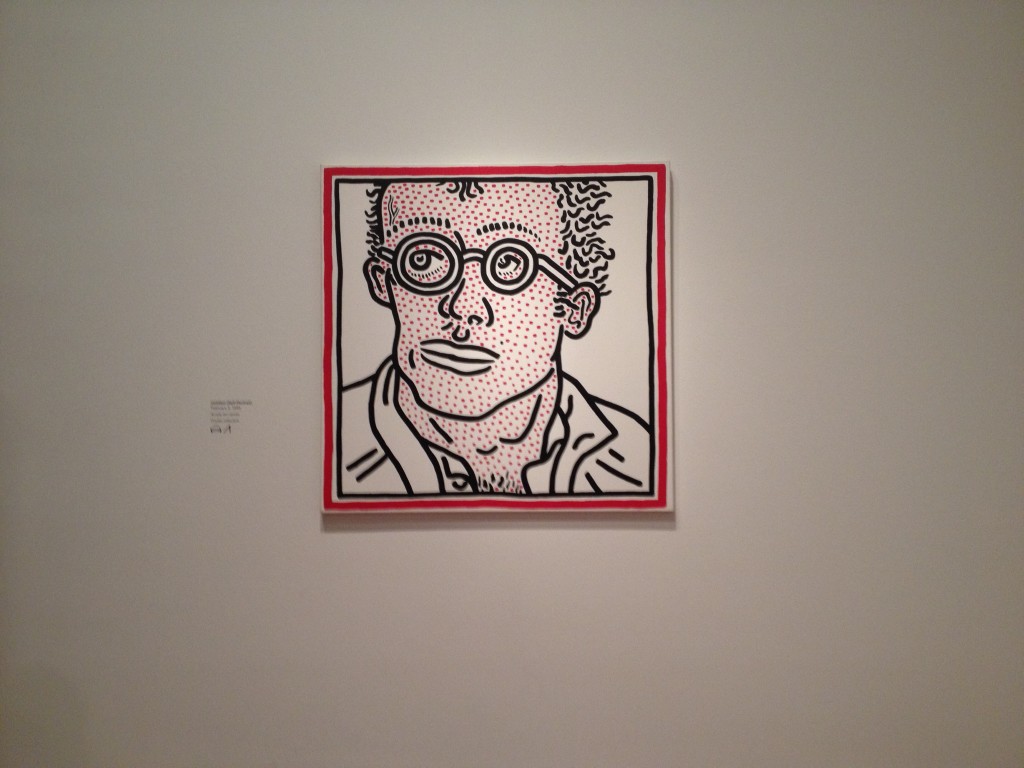

The largely content-specific setup of the exhibit emphasizes both the vastness of Haring’s topical range, and his singular voice, recognizable across the bounds of gravity and levity, of innocence and depravity, and of the personal and the political. It also allows visitors to see Haring react to the changing times in which he lived. His blatantly political works begin with a humorous bend, seen in collages made from newspaper clippings proclaiming headlines like “Reagan Slain By Hero Cop,” but by the end of his career, Haring was making far more sophisticated critiques of consumerism, televangelism, and environmental degradation. Nuanced depictions of sexuality, free from shame but haunted by the paranoia and contagion of AIDS, are typical of Haring’s work. As an openly gay man, Haring was quite confrontational in his sexual imagery, which begins the triumphant work of one coming to embrace his sexuality, but becomes more and more grotesque as his friends, and eventually his health, are claimed by AIDS. The whimsical penis doodles of his early days morph into politically charged hellscapes. The exhibit’s pacing highlights this aesthetic shift, as Reagan Era gloom begins to encroach upon Haring’s work.

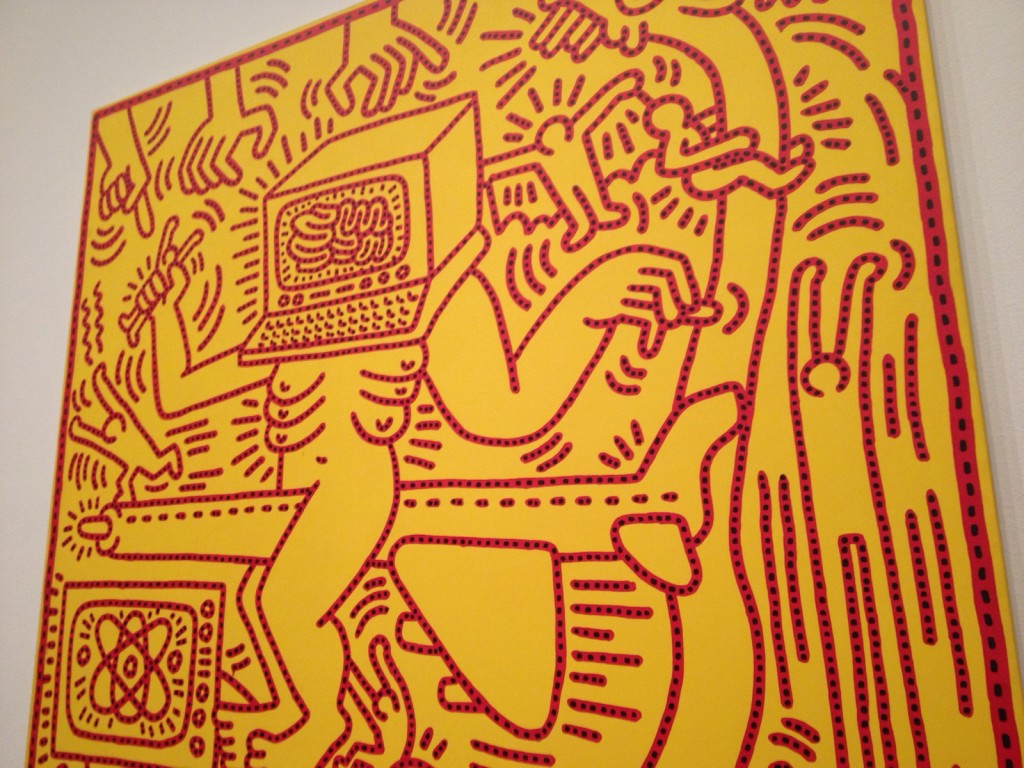

Like any effective political voice, Keith Haring was an expert communicator, bent on creating his own immediately recognizable visual vocabulary. He created symbols: the dog with its animal spirit, exuberant and occasionally destructive, the innocent baby, full of potential, the radiant lines of power that exude from so many of his figures. He used these, and many other repeated motifs, in a variety of ways, but always left enough ambiguity in his paintings for his audience to find diverse and personal meanings. A student of semiotics, Haring was constantly refining and simplifying his artistic vocabulary, getting at the essence of the image. Despite this intentionality, Haring never sketched out or planned his work, but rather left room for improvisation. This gave his work a performative aspect, which the de Young takes into consideration – a documentary about Haring, featuring video of him painting, is played the “media room” right outside the exhibit.

During the symposium that opened Keith Haring: The Political Line, curator Dieter Buchhart told the story of a museum guard who had requested to be stationed in the new exhibit. This guard had seen some of Haring’s art as the exhibit was advertised, and was reminded of the mural in his preschool gym. The figures Keith Haring painted on that school wall decades ago had inspired him to exercise and play. Until the de Young hosted the exhibit, this guard had not known the name of the muralist, but he had always remembered the joyous figures dancing across the wall.

The de Young’s exhibit highlights Haring’s public engagement with audiences like the children who saw this mural. Haring created work for everyone, not just the intellectual elite. Tired of the separation the gallery and dealer structure imposed between artist and viewer, Haring took his work to the streets, drawing over advertisements in the subways and exhibiting in independent storefront galleries. The public aspect of his work made him an instant celebrity in early ‘80s New York, and his life in the spotlight only heightens the impact of his political work. Haring himself became nearly as recognizable as his work, handing out buttons emblazoned with his de facto tag, the radiant baby, to passersby and friends. This penchant for self-promotion eventually manifested itself in the Pop Shop, a store selling Haring merchandise, which led many to decry the artist as a sellout.

It’s fitting, then, that Keith Haring: The Political Line culminates, like all exhibits, in an exit through the gift shop. Far from rolling my eyes at the museum’s attempt to throw kitschy souvenirs at me, I was pleased. Accessibility and personal connection were at the heart of Keith Haring’s vision. His work conveyed messages he believed to be vitally important, and he worked prolifically to share these messages. And if my new Haring phone case helps spread the childlike joy I feel every time I see the artist’s work, it’ll have been worth every cent.