The brutal attacks in Paris earlier this week spurred global outrage, frustration, and, perhaps above all else, a sadness that could be felt around the world. Along with updates every few hours from major news sources and Facebook’s incredibly useful option to mark yourself safe if you were in the area, social media also became the place for people to “Stand with Paris.” This is hardly the first time people have taken to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram and rallied around a battle cry. A plethora of hashtags are circulating even now in an effort to garner support and awareness for social and cultural reform (#ConcernedStudent1950, and #StandWithMizzou were especially popular this week, and for good reason, after threats against Black students were made.)

But what happens when we lose focus of why we’re posting, and who we’re posting for? Almost immediately after the attacks in Paris, my newsfeed became overrun with comments, posts, and pictures intended to display an act of solidarity. The posts in themselves were not worrisome. In fact, it’s comforting to know so many people are informed and care about what is happening in the world; in an event so spirit-crushing, everyone rallied to prove that they did indeed care about a country that had been broken earlier this year in the Charlie Hebdo attacks, and now, again, by suicide bombers.

What is troubling is this: As time goes on, more and more people are posting precisely because of what has become a Paris-themed bandwagon - and everyone is hopping on. The rallying around a cause is not troubling, but how carelessly we do it certainly is. Facebook users began changing their profile pictures to include an overlay of red, white, and blue stripes. Twitter and Facebook became especially flooded with students posting pictures of their time in France with captions (often in French): “Pray for France.” “We are with you.” And yet, this hardly seems to be the time for pictures from the three months you spent abroad in Paris during college. Your smiling face as you stand with friends in front of the Eiffel Tower, or of your wine glass in a bougie restaurant is doing nothing for the survivors in Paris right now who are trying desperately to put their lives back together. It would be naive to assume that no one is posting such pictures of themselves in Beirut because they haven’t ever visited.

When a mass murder happens in Baga, Nigeria, Baghdad, Iraq, or Garissa, Kenya, we pay no attention. All these attacks happened this year, each with a higher death toll than Paris. We don’t even notice when an attack happens the day before in Lebanon. And yet, where are the photo filters for these people? When people die who aren’t deemed important enough to be romanticized by the media, we will, in turn, never be shown that they ever happened. When the “City of Love,” is attacked, however, we will fight until our dying breath to make sure everyone knows we’re “in the know” (online, of course). Showing support has become a performance of solidarity, rather than a true act of feeling.

The outpouring of posts and tweets and hashtags is never a completely good or bad thing. For example, I can see a huge disparity between my friends who do post and those who don’t. Many of my Facebook friends from my mid-sized, right-leaning, often out-of-the-loop hometown in California are still posting recipes and funny cat pictures. On the other hand, nearly all my college friends and professors (spread across the world) are posting about Paris. The optimist in me wants to argue that at least all the posts are keeping us engaged. Still, “engagement” would be a loose term.

“Engagement” would assume two things: that our activism and memory of the event will live on after everyone has stopped posting, and that we are actively acknowledging killings everywhere. The caveat lies in the second assumption, because, as my sister summed up in her status, “It saddens me that people are so ready to mourn the loss of lives in a colonial nation, but overlook the Black, Indigenous and Brown lives lost EVERY DAY in the United States.” She added in a comment, “Where’s the photo filter for this??” She did not receive much support. But she’s onto something. Why are we up in arms about Paris, specifically? Why do we feel we need to claim a stake in it, to the point of writing in their language and dredging up on pictures to prove that we do, in fact, have some sort of ownership over this? The reason is twofold; we want everyone else to think we are a part of things. When one writes in French but only went there on a vacation one time five years ago, what they’re trying to say is, “I’m doing my part. Look, I was there at some point.” The way we compulsively share and add a hashtag to things is the equivalent virtual pat on the back. We’re fishing for likes even as we try to present ourselves as global citizens.

The other reason–less simple, and much harder to swallow–is our desire to romanticize Paris. and our own shortcomings as a biased nation. Consciously or unconsciously, in our own nation and in others, we have already decided whose lives are worth the attention. To some extent, we seem to view France as a sacred space–where white people are the majority, where we like to think that evils like terrorist attacks do not happen. When there is a mass killing such as the one on Friday, there’s an urgency we as Americans feel because it’s a startling realization that our own safety is threatened. On the other hand, when another country like Lebanon is attacked, no one bats an eye because of the prevailing and poisonous idea that those sorts of occurrences are so commonplace that they somehow don’t merit our attention. We feel safe when countries in the Middle East are attacked because we have already written that off as somehow “normal.” When France is threatened, it feels much closer to home. No life is disposable, and yet, what the world media chooses to highlight–and, by extension, what social media users choose to focus on–says exactly the opposite. For everyone else–victims of the slaughters that happen in Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, Nigeria, and in our own country every single day–we write these off as some sort of perverse fact of life. When something like the Paris attacks happen, there is international outcry and a sense of personal fear and anger simply because it’s not supposed to happen that way. The answer, unfortunately, is that simple. These attacks aren’t meant to happen to a country that looks so much like us–romanticized, civilized, first-world, and privileged. To other countries, yes. But not to France. And certainly not to America.

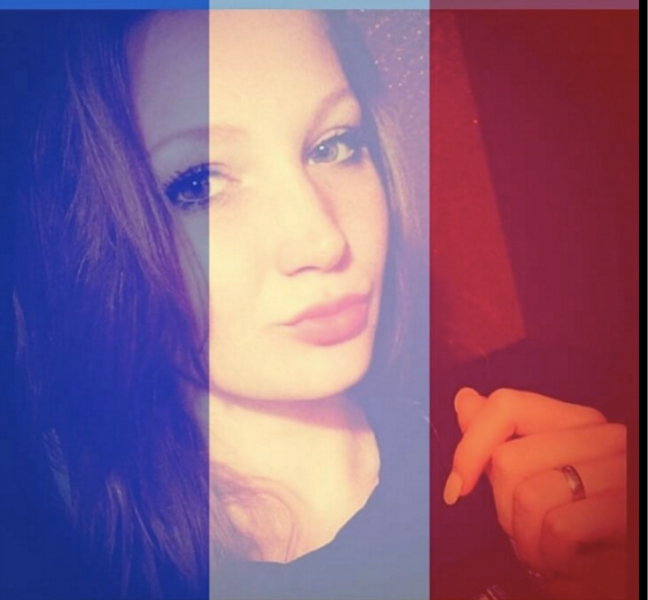

Take Facebook’s option to change your profile picture “in support of Paris.” Facebook offers the same opportunity for students who have a college football game coming up. This temporality seems fitting; do you want to support your school but only for a short time? It’s a great fit for that; the game will be over soon. But the attacks in Paris? Not so easily forgotten. And yet, this trend going viral. What does a nineteen-year-old girl pursing her lips at the camera tell me? Not much, but add the French flag’s colors over her face, and it tells she is thinking about Paris because everyone else is thinking about Paris, because she is told that she should be thinking about Paris, and in a few days her picture will return to its normal duckface and she will go on with her life.

But lives for many French people will not return to normalcy anytime soon, and nor will they readily forget these last few days of brutality. Long after the short term memory of social media and its users has faded, France will remember. And what will our week- or month-long solidarité have accomplished then?

Photo courtesy of here and Sierra Freeman.

RinaChan

November 16, 2015 at 9:09 am (2 years ago)I think you’re very right in the fact that many people don’t actually know what’s going on, and more so that if they do have some knowledge of it that it is without much true feeling that they post supportive pictures. I have to disagree with you on ill-timed complaints of how we as a society are not acknowledging other victims as we should. I don’t disagree with those facts, but I think there is a time and place to say what’s on your mind concerning how crappy of a nation we can be, and now is NOT the time. People are concerned, and even if they aren’t as concerned as you would like them to be posting FB statuses that whine about the little support other victims get during a time like this isn’t exactly tactful. I understand this isn’t about tact, it fact it’s about overcoming social tact and realizing the truth- but no one will listen when all eyes are on this. It is for that reason that comments as your sister made will not be held in support for sometime. At least until people “move on with their lives”.

Nick Taylor

November 16, 2015 at 9:41 am (2 years ago)I just wanted to say that I really appreciate your larger view of the situation. Solidarity should indeed be extended in our larger global community. There have been so many attacks and atrocities that no one pays attention to. People’s solidarity seems to almost entirely driven by coverage in popular media. It is always great to have a well-rounded perspective on the positive and negative but I do wish that more people would show a more broad sense of solidarity.

Thanks for your work.

Nick

Jan

November 16, 2015 at 9:43 am (2 years ago)That was a well written article. It pretty much summed up my feelings on the matter. Thank you

David

November 16, 2015 at 10:15 am (2 years ago)Good piece of writing and an interesting take on how quickly seemingly everyone wants to jump on the overlay bandwagon on Facebook. You make some very good points about how society trends towards following what’s popular and supporting something they probably wouldn’t care about otherwise if not for their social media friends or mass media. Fortunately, not all of us mindlessly post about all over the internet. I do disagree, however, with some of the statements comparing the attack on Paris with attacks that have happened in other countries, such as the ones you pointed out. “When a mass murder happens in Baga, Nigeria, Baghdad, Iraq, or Garissa, Kenya, we pay no attention”. Attacks and deaths, no matter the location, are terrible atrocities, and I do agree that all lives matter. And yes, shame on stereotypical American society for their lack of notice (or care) for these atrocities. But, surely you don’t believe that an attack on an underdeveloped country amounts to the significance of an attack on Paris? I think we are seeing such a strong reaction via Facebook and mass media because this kind of attack is not commonplace among developed countries such as France and the US. As much as we may not like to admit it, for underdeveloped countries, like the ones you mentioned, the death rate is much higher (even if just due to the lack of medicine, food, etc.), and these kind of attacks really are commonplace. Americans are used to this, as is the rest of the world. An overlay of an Nigerian flag over your profile picture isn’t going to make Americans more aware of the deaths happening there. We already know, and an overlay certainly won’t help them at all. While this may be sad, it simply is the situation in those countries. France rarely has any attacks on its civilian population and neither does many of the other developed countries such as the US, UK, Spain, Germany, Italy, Japan, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and on and on and on. Yes, they all have their incidents, but hardly to the scale of the Paris attack.

Steve

November 16, 2015 at 5:36 pm (2 years ago)Thank you very much for this honest critique.

Danny GP

November 17, 2015 at 1:18 am (2 years ago)Well said, I understand people want to empathise with the victims, that’s their choice, even though the motivation and genunity is questionable. But what’s surprising is how big corporations responded, Amazon, YouTube, reddit etc ..all had the French flag on their logo or main page, it shows they’re being selective in their support.