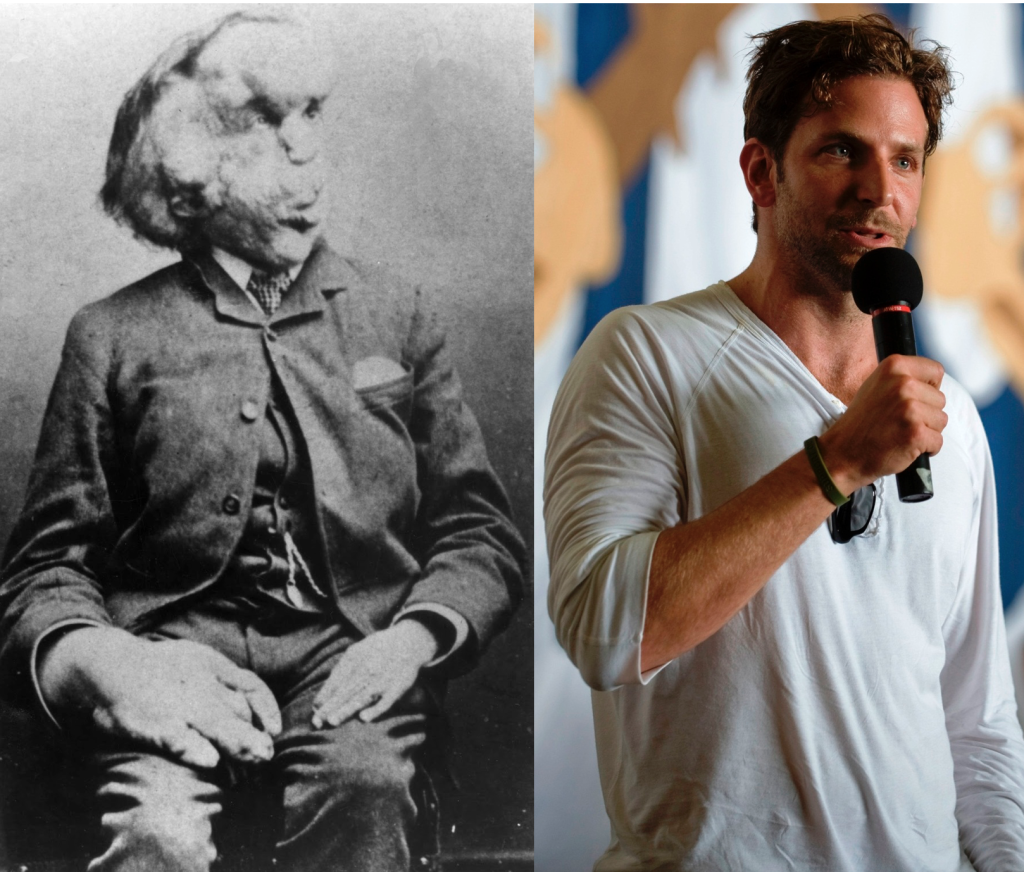

A few hours before I saw “Amy,” the devastating new documentary by director Asif Kapadia, I watched Bradley Cooper star as “The Elephant Man” in London’s West End. When Cooper’s casting was announced for the Broadway iteration of this production all those months ago, I had the same reaction as many people:

“People’s” Sexiest Man Alive 2012 is playing John Merrick? Like… not as a joke?”

I laughed as I tried to wrap my head around what that would look like–I saw no way it wouldn’t be a cheap impersonation, a stretch for Cooper’s limited acting abilities. I read about Cooper’s passion for and history with the play and the character. It’s the role that made him want to be an actor, he says. But still, it didn’t compute. I found myself at a loss as to what it could be about Merrick that Cooper so deeply identified with, two people who couldn’t be more different, and I didn’t give it a second thought.

To put it briefly, I was wrong. Primarily, about Cooper, whose neurotic, pathos-driven, not-to-be-underestimated acting chops have slowly revealed themselves with every movie he’s put out. For me, his turn in “The Elephant Man” is the culmination of this, a profoundly incredible performance that is deeply immersive, self-deprecating, tragic, and surprisingly subtle. But what I left the theater with most strongly was not Cooper’s performance as Merrick, but the ways Cooper’s connection to Merrick manifested itself on stage.

“The Elephant Man” is really not about Merrick, a deformed man in Victorian England who was paraded around as a circus freak before coming into the care of an esteemed surgeon who attempted to integrate him into high society. Merrick drives the story, sure, but playwright Bernard Pomerance makes it clear where his focus lies. In the play’s central scene, at the beginning of Act Two, all of the characters that have met Merrick thus far address the audience and, with some pride, list the ways in which Merrick is “like me.” The repetition of that phrase–”like me”–is key. The masses feel good about themselves for finding–and it feels like forcing–empathy towards Merrick.

This is just one of the boxes that restricts Merrick’s identity over the course of the play. Earlier on, after just being brought away from the hell of circus exhibition, Merrick is told by the surgeon Treeves to repeat the sentence: “Rules make us happy because they are for our own good.” It’s a Victorian creed, but, as we find out, not one Merrick believes. It turns out Merrick is not being brought to Victorian society. It is being brought on him. As “The Elephant Man” moves away from who Merrick really was, it becomes clear that Pomerance’s construction of his story is really not about him, rather the ideologies and personalities that are projected by people onto him.

When you realize this, it is quite easy to see why Cooper’s fascination with this character has endured all these years. Merrick became a public figure, someone for the masses to stare at for their entertainment. Despite the rather complicated and delicate personality that is revealed over the course of the play, by the end, he is no longer himself–just the sum of what other people have said about him.

Being stared at, judged, and categorized, in the public eye–”People’s” “Sexiest Man Alive” 2012 probably has some experience with that.

Genuinely moved by the production, I left the Theatre Royal Haymarket and noticed that the cinema across the street was playing “Amy,” the new film about singer Amy Winehouse that is currently sporting a rapturous 98% on Rotten Tomatoes. I had nowhere to be, so I ducked into the next showing.

Kapadia’s documentary is remarkable for several reasons. You don’t to have be familiar with Winehouse’s music to appreciate it–beyond her most popular songs, I certainly wasn’t. You don’t even have to be familiar with many details of her tragic end–I knew only the Sparknotes version. Kapadia’s take on Winehouse’s life and death in the public eye is so full, so intimate, so all-encompassing, that it’s almost impossible not to walk away with an appreciation for her superhuman talent and a grievance of the loss of such a passionate inner life.

Unlike “The Elephant Man,” “Amy” is really about Amy. Though Kapadia’s job is somewhat more straightforward, as he has what Pomerance could never have–hundreds of hours of concert, tabloid, and home video footage. Kapadia, however, takes it to the extreme. ”Amy” is all archive footage. There are no talking heads, there are no recreations. All we see are innocently-shot home movies that now serve as comi-tragic epitaphs; famous and sometimes infamous public eye images seen the world over, now slid into a new context. Disembodied voices of friends and family guide us through her life. Between it all, we get musical interludes of Winehouse’s music, the lyrics floating on screen to add layers of depth to her art. Never forget–her voice was out of this world.

But at the end of the day, Kapadia is using Winehouse to make a larger point, not the least of which is demonstrated by the archive footage itself–a truly scary amount of her life was lived in the public eye. What was it about Amy Winehouse that, as a friend in the film puts it, “the world wanted a piece of?” One of the choices of footage in “Amy,” an interview between Winehouse and Jonathan Ross from 2004, offers one answer:

“You know what I like about you?” Ross says, “The way you sound so common. Because, you know, I’m common, and it’s refreshing to hear someone speak like they haven’t had elocution lessons.”

He might as well be listing the ways she was “like me.” True, Winehouse did come from a rather plain middle-class background, but was this the reason she caught the media’s attention so strongly? Later on, after Winehouse has won a handful of Grammy’s, the paparazzi becomes worse than ever. The paparazzi footage Kapadia chooses is a particularly hellish flair of flashing lights and disorienting movement, and most strikingly a chorus of voices calling her name–”Amy! Amy! Amy”–and asking her questions as if she were an old friend. They take her picture and hound the poor lady with a intimate familiarity that clearly isn’t reciprocated.

Then comes the downfall, as Winehouse slowly but strongly becomes addicted to alcohol and other drugs. Attempts at rehab don’t stick and somehow she is still allowed to tour. Late-night talk show hosts joke and family members seem to turn the other way. Kapadia has said he was first interested in this project because of the question of “how.” “I never really understood how that madness was going on down the street from where I lived,” he said to Vogue, “and nobody stopped it.”

The answer is sadder than fiction. Early on in the film, Winehouse tells a reporter that her idea of success is being able to make music when she wants, how she wants. But then the realities of the music industry kick in, she’s boxed into commitments, and the name of the game becomes money. Finally, over footage of Winehouse’s body, killed by alcohol poisoning, being lifted in an ambulance, her bodyguard relays one of her final quotes to him: that she would have given it all back, all the music and all the money, just to be able to walk down the street without being harassed. It’s a heartbreaking sentiment, but one that beautifully summarizes Kapadia’s construction of Winehouse’s life, which also seems to be the thesis of “The Elephant Man”: the world saw something they wanted a piece of, and they got it.

Now the question becomes: are we okay with that?

Seeing “The Elephant Man” and “Amy” in such close proximity to each other was either some cosmic alignment, good planning, or just a wonderful coincidence. In any case, something is very, very evident to me.

John Merrick knew a lot about Amy Winehouse, and Amy Winehouse knew a lot about John Merrick. Even if they had never heard the other’s name.

Photo credits: here and here and here and here.