In The Laramie Project, a New York theater company travels to Laramie, Wyoming to write a play about the town where Matthew Shepard’s was beaten to death in 1998. Over the course of a year, they conduct over 200 interviews, but a single request made by the town’s Catholic priest stands out: “If you write a play about this, say it right, say it correct.”

James Sherwood (‘17) and Zachary Dammann’s (‘18) TAPS capstone production of The Laramie Project is done right. Their production and directorial choices only strengthen the powerful script; any weaknesses come from flaws in the script itself. As Dammann writes in his director’s note, The Laramie Project is one of the “stories that need to be told.” Their powerful production casts empathy and complexity over a town that, because of the infamous hate crime committed on its borders, could have easily been simplified as bastion of hate.

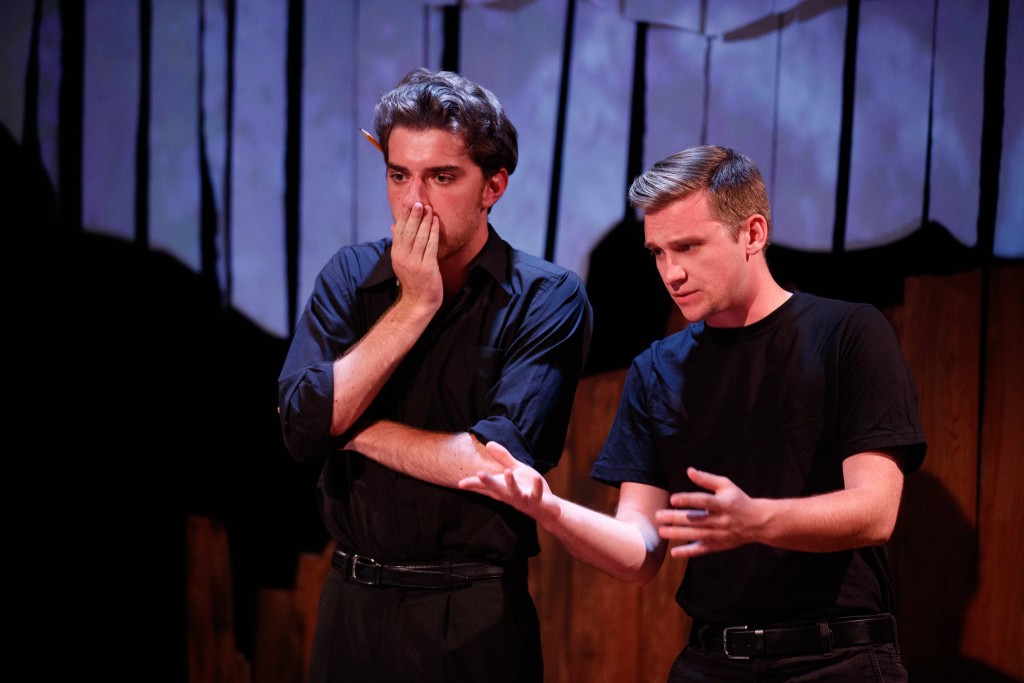

The delicate balance between accountability and empathy that The Laramie Project depicts in both its individual characters and its portrait of the town as a whole would not be possible without versatile, strong acting. Each actor plays several characters, many of whom come from dramatically different experiences and beliefs. Though the large number of characters presents an acting challenge, this production’s cast as a whole demonstrated believable acting. Brenna McCulloch, Malaika Murphy-Sierra, Matt Herrero, and Matthew Libby in particular stood out for their honest and diverse performances. Each of McCulloch’s characters—but especially her portrayal of Romaine Patterson, Shepard’s hometown friend turned counter-protest activist—was charged with earnest sincerity. Murphy-Sierra’s raw characterization of the emergency room nurse who treated both Matthew and McKinney, his attacker, especially stood out among her many realistic characters. Herrero and Libby were both incredibly impressive. Herrero played the boy who found Matthew tied to a fencepost and wrestled with his role in the tragedy. He also played Henderson, one of the perpetrators, who he embodied in such a complete way that he became almost unrecognizable. Libby, too, showed great depth in his characters from his talkative Galloway, the self-declared key witness in the case, to his shattered, strong Mr. Shepard.

These characters, though always changing, remained on stage throughout the production. Their subtle handling, hiding, and trading of props that helped delineate their characters (a pair of glasses here, a pocket Bible there) was choreographed deftly. This blocking, which could easily serve as a distraction, instead further strengthened the production. The constant presence of all the actors made it more difficult to separate the “bad” from the “good;” instead, each person was complex. One of the most exemplary moments of this came when a leather and spike-clad skinhead approached the anti-gay protesters at Matthew’s funeral. He did not start a fight; he started singing “Amazing Grace,” in which other characters joined in and continued through McKinney’s confession and sentencing. The script was smart to contrast Henderson’s trial with McKinney’s confession, but Dammann’s blocking of these scenes was smarter. Henderson faced away from the audience and looked down for most of his trial, while McKinney made his confession facing out to the audience, forcing the audience to confront both the brutality of his crimes and the humanity of his individual self.

In the same way that you as the audience must see, through the graphic descriptions of Matthew’s injuries, his brutal victimization, you must also see McKinney as a human with a face and a young child. You must see the old teachers who will not desert Henderson, the pastor who wants to save McKinney’s soul but not his body from the electric chair, the student actor who can never quite “agree” with homosexuality, the doctors and detectives and students who break down and lose friends when everything they thought they knew about their town and themselves shatters. Against the stunning mountain-line set and the white muslin strips that change from sky to snow to stars thanks to the depth of the brilliant lighting and projection design, you see Laramie. You see people who are never quite perfect and never quite evil. You see people who have to mourn Matthew, to mourn the town they thought they knew, and to mourn and an overwhelming reality: “we are like this.” It is not just the hundreds of Laramie residents who are “like this,” it is all of us who must think about and mourn that we live in a country where hate can dictate action. We must recognize our complicity in this hate, and move forward with what both Matthew and this production of The Laramie Project leave us: H-O-P-E.

Photos courtesy of Frank Chen