imagesBy(Victor Liu,Eric Eich)

I.

I’ll be upfront about it: I am a fangirl. This weekend I met some people who I admire, people who will almost certainly forget all about me.

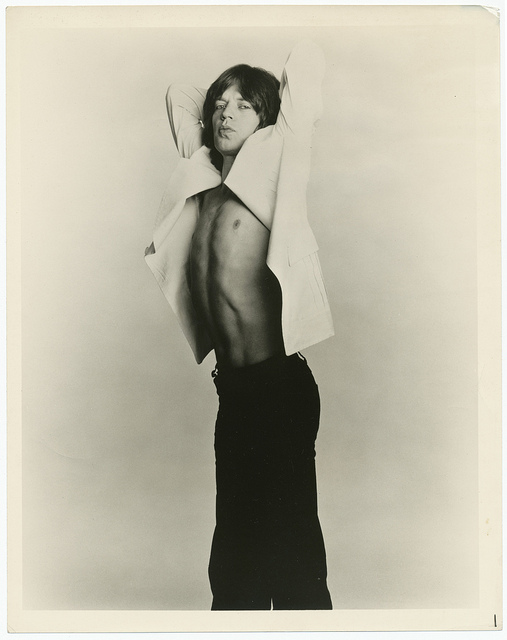

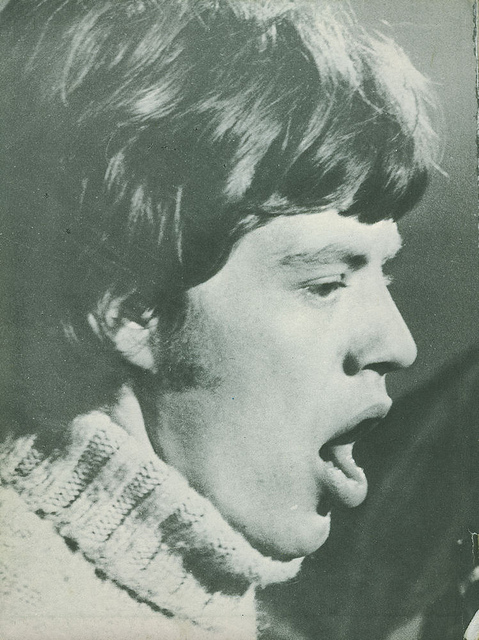

I recently watched Robert Frank’s 1979 Cocksucker Blues, which follows the Rolling Stones on their US tour, and like everyone else in the audience, was theoretically fucked for 90 minutes by a young Mick Jagger. We sat in giddy, shifty silence as the camera zoomed in on his infamous lips, cut to a couple roadies shooting up, and lingered on a woman whose stomach was striped with cum. Perhaps I carried these images with me when I went to see The Horrors last Thursday night at The Fillmore; perhaps I let my experience be colored by the concept of a rip-roaring 1970’s, my brain stuck on Super-8, my heart aflutter at the slightest instance of ill health.

For those who don’t know, The Horrors are comprised of five lanky, ghosty, lovely lads: imagine The Velvet Underground cast in a fucked-up production of Sweeney Todd. Their sound has shifted over their past four albums from riotous, wall-scaling punk, the sort that makes you want to commit bodily harm in the most fun way possible, to a floaty, breathless brand of bootgaze that makes you forget you have a body at all, save for two dilated pupils and set of batting lashes. Their music, their antics and this singular brand of Beelzebub chic have garnered them a massive following, teenage fangirls flocking to them as to a goth One Direction. If Cocksucker Blues depicted a rock-n-roll free-for-all, The Horrors’ sound is that with a conscience, a well-read bacchanal or backwards free-fall (into THE ABYSS!), a bit like those videos where someone yawns in slow-motion—a release so tortuously slow as to be no release at all.

The Horrors are vampiric not in pallor or in garb but in the desire they awaken to be drained, to have your vitals slowly siphoned and your mind pushed to a mossy edge. The void is a head-rush, and The Horrors exploit this. They toy with the exhilaration of a public faint. Though definitely dreamy, theirs is not a sunbaked Beach Boys dream, as made clear by their attire more Oscar Wilde than wild child; a close listen to their lyrics will reveal a through-line of regret, of more than a few bruises beneath the double-breasted coat.

“Take your love,” Faris rasps. “And take your tomorrows/Because your love/isn’t enough.” Their songs aren’t sad, per se, in the way that the Stones’ “Angie” is clearly a farewell, but neither are they upbeat. If musical genres were divided by night and day, The Horrors would inhabit the wee hours, the point at which the light is shifty and the mind set free by sheer exhaustion. If songs like “Sleepwalk” arouse sadness (and they do, at least for me), it is a sadness anatomized, pulled apart, to reveal its ambivalent pieces, no bleeding heart but bleeding gums that, as one knows, sting so good.

Another more complicated motif in The Horrors’ lyrics is vision. Their latest album has two songs called “In and Out of Sight” and “I See You,” while the album before that has “I Can See Through You,” and “Wild-Eyed.” This sight-specific theme is particularly interesting for a musical group that traffics in darkness—not the doom-and-gloom darkness of emo (if that even still exists) but literal dimness, the shadows outlining a backlit object, the swimmy darkness that awaits you when you finally pass out.

On a more basic level, for the uninitiated (read: non-fangirl) listener, the members of The Horrors might seem interchangeable. They are all skinny boys of a similar age with a similar dazed half-smile, all dressed in a similar uniform of black cigarette pants. Three of the five wear their hair long, and Faris’ is especially matted: for as swept away as I was by the show, I found myself wondering how he could possibly see from behind his bangs. This isn’t incidental; I would say that the central appeal to The Horrors, music aside, is the line they toe (with those infamous steel-toed boots) between clarity and confusion, the visible and the purposefully dim.

It is not just ironic that while Faris intones, “I can see your future in it, I can see it there,” the audience struggles to see anything beneath his fringe: it is also titillating. The same goes for every band member as they rock in and out of personal trances: that sudden flash of eye-white is a shiver-inducing validation—yes, he does see me! ME!—, a thrill as Sartrean as it is schoolyard. Faris, the unpossessable (and for many fangirls, illegal) object of desire, looks literally possessed: in the rare moments that you see them, his eyes are wide and his gaze erratic. Watching The Horrors perform is like a game of spin-the-bottle in which the bottle never stops.

Ouija genii, foggy folk, The Horrors gloss over the differences that in real life matter so much (between eras, genres, individual identities) and thus the listener slips and slides on the resulting gleam. Mick Jagger was more extreme with his boundary-bending, as underscored by Cocksucker Blues’ many close-ups of the superstar painting his lips, shimmying into a jumpsuit, or fretting his Faris-length curls. The dimness of The Horrors show is a release, just as turning out the lights is a release from one set of social obligations to a new, more nebulous one. This is the true beauty of obfuscation, which takes many different forms, the most obvious of which are drugs and costume (Mr. Jagger’s spiked cups of tea): that when nothing is clear, so much more is possible.

As Faris lurches across the stage like a man with acid in his eyes, one pines against the odds to be seen. The exact object of his attention has been blurred by hair, dimmed by lights, obscured by drugs, collectivized by lyrics, made anonymous by grammar (if I lose YOU i’ll go mad); and in the resulting disarray, anyone can make believe that they’re the epicenter of this tussle, that they fill the niche suggested by his pronoun. In the darkness of the concert hall (a darkness mirrored by the slender men onstage) one feels the most visible; in the thrall of hazy music, one feels the most had. “Open your eyes,” Faris demands. But really, one prefers this intoxicated game of I Spy, this shared delusion in which you, and everyone else in the room, are The One.

II.

This confusion/clarity divide can be further extended to real life. On Friday, I went to see two members of The Horrors DJ at a shindig in San Francisco somewhat suspiciously called The Acid Test. The name of this party should’ve been warning enough, as should’ve been the exuberant advertisement, “Come get your nostalgia on!”

I entered what looked like a Mad Men-themed party for swingers. People in polyester costumes did approximations of the mashed potato and posed against the tie-dyed wall. Half the crowd was youngsters acting out a propagandist notion of free love; the other half was single men in moth-bitten bell-bottoms, grooving with geriatric abandon. A Gandalf-esque man with a game-face controlled the lights, drenching The Horrors’ bassist and drummer in a leprosy of color. The music was a squiggly departure from The Horrors’ pensive moonscape of the night before, a let-your-hair-down set that blew bubbles in the blood.

The superb DJ set, however, could not distract me from the revisionist history hippie hippie shaking on the dancefloor. I felt acutely embarrassed for all parties involved, myself included. The lights were not dim enough, literally and figuratively; it was clear how hard the partygoers were trying to relive a Party City fantasy, to inflate a Technicolor past (of beehives, Jagger, blotter acid) while skating over all its flaws. What was so exciting to watch unfold on film, The Stones’ debauched parties and general zigzaggery, made me blush when acted out. This cartoonish enactment of the sixties was not just embarrassing, but morally suspect.

But who am I to judge? Remember, I’m a fangirl, in whom shyness and delusion fuse. I’m certainly no stranger to the ecstasy of revision. Who could know this better than a fangirl and/or introvert, for whom pursuit is never possible? In Cocksucker Blues, Mick sighs, “I could go days without talking to someone.” He looks mournfully off-camera and all the world adjusts their underwear. The man on the pedestal further isolates himself (It’s lonely, lonely at the top); his fans tilt their heads back and dutifully squint. For fangirls and the chronically nostalgic, distance is the name of the game. We idolize what cannot be, what we can’t have, what never was. We are acutely aware of that fact that life happens but once—no amount of color-saturated daydreaming will grant you a do-over. But goddammit, we try.

I’m the type of person who will get all dressed up with one person in mind, then spend the whole night avoiding them. That’s what I did at the Acid Test: when I finally got the chance to talk to the members of The Horrors, I looked away in stoned defeat. I couldn’t face the musicians I had idolized since age 14. Their signature dimness was stripped, replaced by a streetlight; how could I face the facts, the flesh, the British teeth? This is not to say that they weren’t lovely in person, but they were just that, in-person, and physicality is where the dreamer freaks. Pursuit is only feasible when all is hazy, as in a crowded concert hall, where questions (does he see me? does he care?) hang alongside the smoke in the air. As for polite conversation with a person I admired, the clear-cut nature of the exchange—hello, how are you? fine, thanks, and you?—proved too overwhelming.

We all find ways to muffle the brute truths of our world. Some methods are more ethical than others. Nostalgia is an advanced form of this shyness, this inability to be bold or upfront taken to the cultural extreme. It is oftentimes the only way that one can face the failings of our past: it is loss bejangled, shame trademarked. The 1960’s were a fucked-up time, creative, yes, but corrupt too, and it is no coincidence that this troubled era is one of the most glamorized. Where there is shame, there are spangles.

My own generation is fond of romanticizing the 1990’s, a hilarious concept considering most people I know spent that decade in diapers—what do we know of its highs and its lows, beyond a vague memory of Nickelodeon’s lineup? Rwanda was a blip on my radar, Y2K and AIDS nothing more than funny words. Instead of owning up to a complicated history, we rose-tint our atrocities, play hide-and-seek with ghosts. We have parties where we play the Backstreet Boys. Cocksucker Blues makes the objectification of women look sporting; one of the only times we hear Frank speak is when he tells a bare-breasted junkie that she has a great smile, and on cue, she hams it up for the camera. With crafty editing and psychedelic lights, nostalgia all too often turns the shit-show that is history into a beauty pageant.

A haze, as created by The Horrors’ entropic synths, can set one free (as evidenced by the evangelical slamdance of band and crowd). A haze, as generated by large-scale cultural shame and facilitated by nostalgia’s blinking lights, can just as easily trap.

Thwarted fangirl, I too have my methods for fogging the facts. I keep the things I love just out of reach, at that magic point at which they’re visible (though barely, black suit grading into blackened stage) but untouchable, literally and figuratively. I am no better than the baby boomers boogying to Beatles mashups. We both require distance from the truth. We have a hard time looking the things that matter in the eyes.

I don’t want The Horrors to forget about me, despite how forgettable I was. I replay in my brain all the things I should have done instead. I write now, mostly, to atone for my fuckery. This is my small-scale do-over, sans costume or lights. Do I find courage in retrospect, or courage in fantasy? Shit like the Acid Test makes me realize that the two are interchangeable.

Mick Jagger was the ultimate fantasy-object because he was a master at keeping his audience wondering. I’d argue that The Horrors do this too (though less pointedly and pelvically) and their legion of devoted fans would probably agree. I know it, one pants to another, I know that he was looking at me. But what happens when they actually are, expecting an answer over the tip of their Menthol? Outside a tiny club in the makeshift smoking area, the clarity is terrifying. What to say?

Better to stay silent and pine (or write) about it later. Better to imbue every gesture (a toss of hair, a glinting eye-roll) with undue importance, just as nostalgia shines its privileged light on a select handful of objects—mini dresses, funky lights, skinny British lads. Forget the gory shit, like Vietnam. Forget that you are not The One but just a number, love.

We want the world diluted, all its comedowns and letdowns extended indefinitely. There is a time and place for forgetting oneself. Intelligent, hair-raising music likes The Horrors’ grants us this diversion, this entre into a liminal space where anything seems possible. Make no mistake: this constructed dimness is not the same thing as denial. One can have their vision blurred without being blindfolded. One can head-bang without burying it, likewise, in the sand. Take it from a fangirl, who does both.