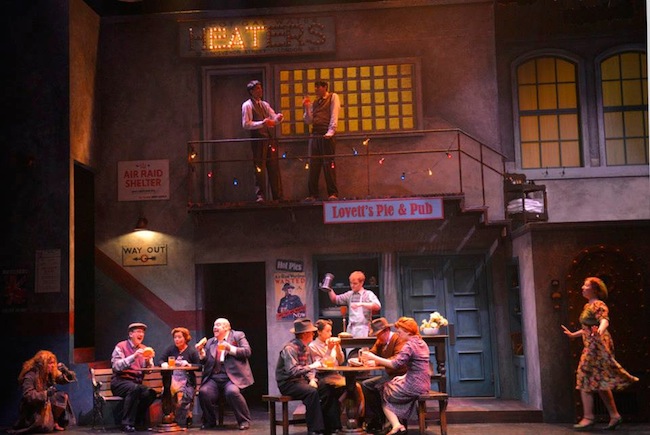

Audiences might remember a ghastly, gothic Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, fueled by the turmoil of the 1840s. They might remember sets made of curvy London streets, or grim lighting, or dark 19th century attire—but not wailing sirens, “Way Out” signs, or air raid worker recruitment posters.

The production at hand is TheatreWorks’s version of Sweeney Todd, one of Stephen Sondheim’s most beloved musicals, now playing at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts. Director Robert Kelley (Stanford Class of ’68) has decided to give the classic a unique twist, setting it during World War Two. And we are, in fact, caught in two wars: Germany’s sustained bombing campaign on London (better known as the Blitz) and the beginning of Todd’s own gruesome campaign for vengeance.

In the first scene, young, optimistic sailor Anthony Hope (played by Jack Mosbacher) praises the “city bells” of London; having just returned from a long voyage, he is ecstatic to be home. But our ears still ring from the air raid sirens, and we are more inclined to agree with Todd when he mocks Hope for his naiveté, singing that London is a “great black pit.” Given Todd’s backstory—he was exiled by a corrupt London judge, so that said judge could pursue Todd’s beautiful wife—we can hardly blame him for his pessimistic worldview. But make no mistake. The design of Kelley’s London is exquisite: rusty bronze buildings rise up, two stories high, to frame the infamous Fleet Street where Todd carries out his grisly deeds. They symbolize both the cost of modern development and the exhaustion of war, so that even beyond the dark costumes and grim lighting that characterize traditional productions of Sweeney, this particular show is very much a work of atmosphere—and it works.

If Sweeney Todd is a war, then Todd himself is a human bomb. David Studwell plays this role with a one-track mind: his Todd is obsessed with revenge, refusing to be coaxed even momentarily from a path of grim destruction. Eventually, when his goal is thwarted, he decides that all humans deserve to die, and begins killing indiscriminately, as practice for his planned murder of the Judge. The people of London become collateral damage, eventually baked into meat pies by Mrs. Lovett (Tory Ross), Todd’s opportunistic partner-in-crime. We are tempted to think they are mad; but Studwell and Ross make it clear that their characters are not. Todd is driven, Lovett is cheerful, and they are both clear-minded, which makes them even more terrifying. A pair of perfectly sane human beings, merely willing to go to any lengths for what they want—and to hell with whoever gets in their way.

From the corrupt Judge Turpin (Lee Strawn) to the lovesick Hope, the other characters are similarly straightforward. They—and the Greek chorus that appears intermittently throughout the play to comment on the action—remind us regularly that though Kelley’s Sweeney Todd has an impressive backdrop, it is still a story. Given that Sondheim was inspired by a series of sensationalist novels, this is hardly surprising.

A quavery note does rise above all the doom and gloom: not the young lovers Hope and Johanna (Mindy Lym), as one might expect, but Tobias Ragg, played by TheatreWorks newcomer Spencer Kiely. “Nothing’s gonna hurt you,” the simple-minded boy sings to Mrs. Lovett, “not while I’m around.” This scene, near the end of the final act, is reminiscent of children comforting each other in the darkness of an air raid shelter. Kiely makes Toby one of the only genuinely innocent and lovable characters in this show, and the futility of his efforts to protect Mrs. Lovett is that much more heartbreaking. The audience watches, feeling the helplessness these characters face, as the story draws ruthlessly closer to an end. It is indeed just a story; and, like any story, it is as inescapable as human nature.

It is at the end of that story that Kelley’s artistic vision and Sondheim’s music finally coalesce. Madness rampages through the streets when the inmates of an asylum are freed; flames dance as we hear the whistling of imaginary bombs overhead. When the smoke clears, Hope, Johanna, and the audience are left with the plight of every post-war generation: how, in the ashes of violence, do we live on? How do we rebuild? And how do we cope with the rediscovered fact that all of us—“even you”—are capable of such destruction, that it lies inherent in humanity?

The story closes, though with one last verse from the Greek chorus. The actors take their bows, exiting from the stage. And we leave, content with the story we’ve been told—yet unsettled by the mirror Kelley has held up for us, as if, in the air, we smell a tinge of smoke.

Photo credit: Kevin Berne