Untitled, from the series Women of Allah

Shirin Neshat

1996

Gelatin silver print with pen and ink

Media representation lies at the center of the study of discrimination. From the dominance of the male gaze to rampant racism, the media has colonized visual culture with its hegemonic imagery. The media’s sexualization of the female image and ethnic stereotyping transform actual women into mere objects and nuanced cultures into extreme caricatures. American artists such as Jenny Holtzer and Barbara Kruger have fought against media discrimination by appropriating magazine covers and advertorial billboards to populate visual culture with feminist imagery. She Who Tells a Story, a newly-opened temporary exhibit at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, similarly undermines the media machine through the media’s own vernacular. All using the same medium of photography, a group of twelve female Middle Eastern photographers give themselves the voice that had been doubly silenced by media sexism and racism.

The opening piece of the exhibition demonstrates this gaining of voice in graphic, impactful black-and-white. This photograph from Shirin Neshat’s Women of Allah series shows the collapse of barriers that keep women silenced. A hijab-clothed woman, fingertips to her mouth, seems to be tentatively un-silencing herself. Here, Neshat overturns normative expectations of Iranian culture by using Iranian culture to empower the subject. Specifically, Women of Allah, in its very title and its heavy use of text, calls to mind the Qu’ran. However, the text is actually the poetry of radical Iranian women writers and features the intensely self-willed themes of love and desire. The poetic calligraphy inscribed onto her hands, patterned like runes, seems to course through her veins like a current of magical power. The words are as much of the woman’s body as her skin and bones, and, with lips beginning to part, she will not be silenced any longer. Finding power in the written word and overturned expectation, she uncovers her mouth, and dares to speak.

From the series Mother, Daughter, Doll

Boushra Alutawakel

2010

Pigment prints

From the series Mother, Daughter, Doll

Boushra Alutawakel

2010

Pigment prints

From the series Mother, Daughter, Doll

Boushra Alutawakel

2010

Pigment prints

Following the exhibit’s visual statement of purpose, Boushra Almutawakel’s nine-image series, Mother, Daughter, Doll, is its call to action. The series demonstrates, with a sense of alarm, the encroachment of media forces upon Middle Eastern women. The image of a picture-perfect mother, daughter, and doll, a warm smile across their faces, soon sours. Throughout the course of the series, the women’s expressions turn somber as their apparel transforms from hijab to burqa. From casual street-clothes into dark, full-length veils that engulf their bodies, their humanity is obscured, leaving only a haunting, black void.

The language of mass media is the target of critique here. With each successive photograph, the figures are increasingly covered and grim in expression—transforming them into the heavily veiled, dehumanized media stereotype. Which type of veil Muslim women wear and even whether they wear veils or not is a product of both local culture and personal values. However, the media slanders the entire Islamic culture by enforcing the very idea of the veil as oppressive, becoming itself an agent of oppression. Almutawakel imitates the way that media exposure obscures rather than promotes authenticity; with each successive photograph of the series, the subjects rapidly approach caricature.

An article by award-winning writer Moustafa Bayoumi discusses a post-9/11 directive that CNN issued to its reporters, which deemed that even “detached compassion” for Middle Eastern peoples in its reporting, even during wartime, was “perverse.” She Who Tells a Story seeks to articulate more accurate accounts of its subjects. Truer to the photographic medium, reality is being captured on camera, rather than the distorted reality of the photographer’s agenda.

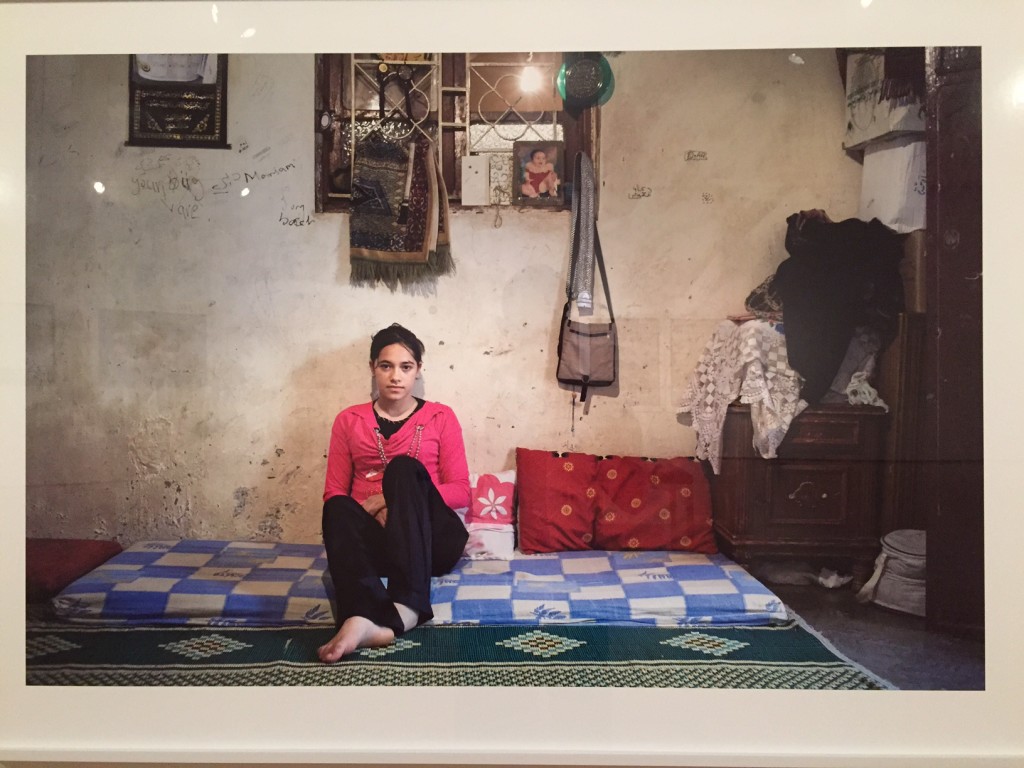

A Girl and Her Room

Rania Matar

2009-2010

Pigment prints

Miriam, Bourj al Shamali, from the series A Girl and Her Room

Christilla, Rabieh, Lebanon, from the series A Girl and Her Room

Rania Matar’s series, A Girl and Her Room, examines teenage girls in their bedrooms in the Arab world. As opposed to the shocking imagery of soldiers and destruction which Western, CNN-tuned audiences are accustomed, Matar closes in on domestic scenes and provides the faces behind the headlines. These stories are subversively individuated, as the girls physically isolate themselves from the tumult of the outside world. Viewing these photographs is an intimate and personal encounter. The girls are also allowed agency in the creation of their own images. In opposition to voyeuristic and self-serving media practices, the girls pose and arrange their rooms at will, working with the photographer to convey their identities. A sense of diversity too, is conveyed by the series. The photographs, featuring girls in vastly different styles of dress and rooms with a variance in décor, create a diverse broadband of representation. Rather than reducing them to monolithic stereotypes, Matar expands visual notions of Middle Eastern women far beyond the bleak, burqa-clad media stereotypes Alutawakel’s piece. These girls are different from the ones we see in media and, at the same time, not so different from us.

People visit art museums to see themselves on the walls—to find an emotional resonance in the images. She Who Tells a Story means to portray Middle Eastern women as not impenetrably and unchangeably different, but containing an innate, shared humanness. No longer merely subservient, veiled captives in permanent warzones, these women show us what is beneath the veneer of media construction. From diversity, we find similarity. In this spirit, each artist conducts a different yet related project to the same end. Neshat demonstrates empowerment, Almutawakel displays media dehumanization, and Matar empowers her subjects to undermine the media. Each of the twelve photographers expresses herself in a way uniquely grounded in female identity and local culture.

As the woman in Neshat’s photograph begins to speak, in response, so do we. Collectively, we engage in worldly dialogue and an alliance against oppression, unhindered by the boundaries of geography.

***

She Who Tells a Story will continue to be on view at the Cantor Arts Center through May 4th, 2015.

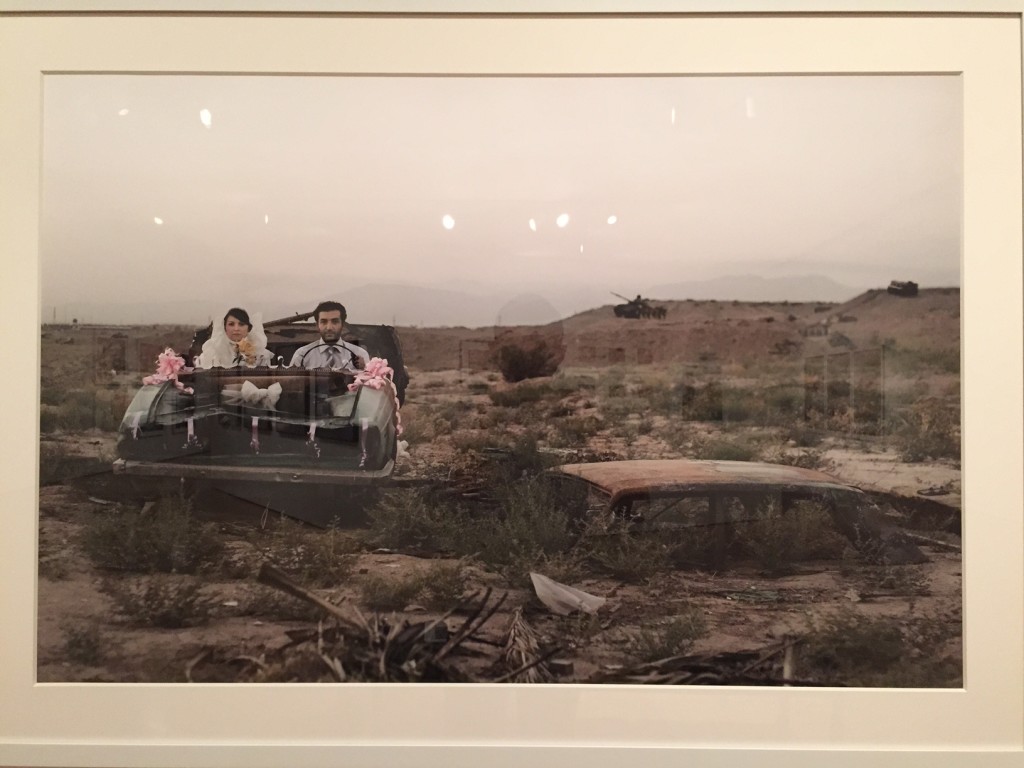

Untitled #5, from the series Today’s Life and War

Gohar Dashti

2008

Pigment print