At first, walking in to San Francisco’s Pier 24 feels a lot like being in on one of the bay area’s best-kept secrets. The building’s façade is inconspicuous and barren when compared to those of San Francisco’s more traditional museums (De Young, SF Moma, Legion of Honor, etc.). Only a small plaque reading “Pier 24” sits beside the garage-style doors. In the shadows of the Bay Bridge, the old warehouse looks more like the scene of a sitcom drug deal than the largest gallery space in the world dedicated exclusively to the display of photography.

At first, walking in to San Francisco’s Pier 24 feels a lot like being in on one of the bay area’s best-kept secrets. The building’s façade is inconspicuous and barren when compared to those of San Francisco’s more traditional museums (De Young, SF Moma, Legion of Honor, etc.). Only a small plaque reading “Pier 24” sits beside the garage-style doors. In the shadows of the Bay Bridge, the old warehouse looks more like the scene of a sitcom drug deal than the largest gallery space in the world dedicated exclusively to the display of photography.

For all sorts of reasons, the museum’s location is highly unusual. Built in 1935, Pier 24 used to serve as the departure dock for ferries headed to Oakland. Andy Pilara, an investment banker, rented the space to house his growing collection of photography. Pilara had never shown an interest in art before buying a Diane Arbus photograph from Fraenkel Gallery. Seven years later, Pilara had purchased entire sets of extremely important photographic series such as Garry Winogrand’s The Animals. Eventually, his collection became so expansive that it was clear he needed a venue for storage and display. When the Pilara Foundation bought the Pier 24 several years ago, it had stood as a vacant warehouse for over thirty years. The murky water of the bay was visible through the thick wood-slatted floors, and the high-beamed ceilings served as a seagull’s reclusive paradise in the midst of a crowded city. To some, installing a photography exhibition space that floats on salt water seems impractical. The salty air, dense atmosphere, warm temperatures, and sunlight all stood as potential threats to the fragile, impressionable medium of photography.

Pier 24 has faced each environmental obstacle with innovation and an aesthetic eye. The building is completely climate-controlled and light controlled and creates a zone of artistic contemplation in one of the most competitive real estate areas in the United States. After walking through the doors, visitors must wait for the outer door to close before entering the gallery. This procedure minimizes the potential damage of salty sea breeze that could enter the galleries. Although not an ideal location for a photography viewing space, money was not an obstacle for Pilara. He was willing to spend whatever possible to make the ocean-front building a compatible storage facility. Pier 24’s mission is simple: to create an area of quiet contemplation dedicated completely to works of photography. The photos have no wall labels or even artist’s names attached to them. Rather than being blatantly presented with context and meaning for each piece, viewers have the unique opportunity to lose themselves in the compositions and discover their own narratives for the works.

Additionally, although free and open to the public, visitors must sign up in advance to tour the space. Pier 24 puts a daily cap on how many people can enter the space so that viewers have the opportunity to experience an intimate one-on-on connection with each work without the interference of a bustling, noisy crowd. The result is a realm of peaceful contemplation and self-exploration in conversation with the photographs.

Although Pier 24 is technically free and open to all, there are indeed barriers that create implicit obstacles for members of the general public. While the “initiated elite” of the Art History world can get lost in the compositions and appreciate the lack of wall text, people with little background information in art may lose some of the significance of the work when given no context or explanation. Additionally, Pier 24 is open only during normal business hours Monday through Friday. This means that anyone who is not his own boss – i.e. most people – cannot attend their exhibitions. Pier 24’s lack of general explanation of their pieces and inflexible business hours turn a cold shoulder to members of the non-artistic, mass public audience. Even for the initiated few, the vast majority of Pier 24’s works remain hidden in storage. While Pilara owns entire series of multiple collections, these pieces are not available for study except when on display.

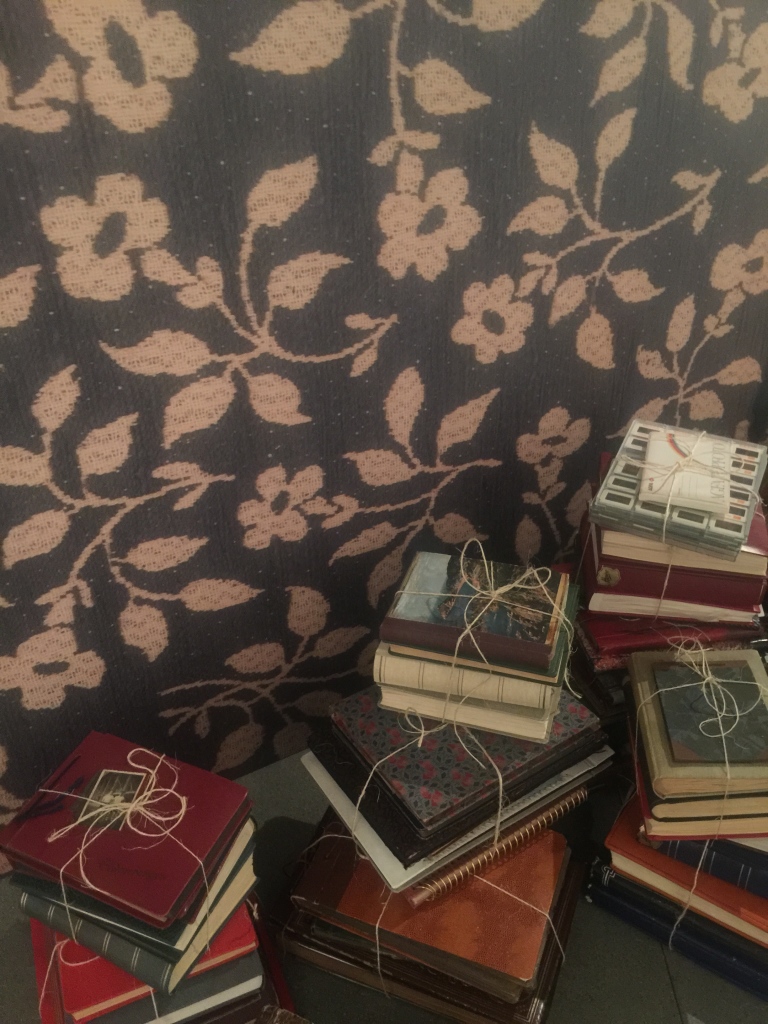

Pier 24’s current show, Secondhand, explores the grey area between artist and curator in the realm of secondhand images. That is, the installation of pre-existing images in a new, artistic context to reveal significance. The show features the work of artists who collect found images and edit, arrange, and manipulate to create completely new works. The shows features work from photography giants such as Richard Prince, John Baldessari, Larry Sultan, Erik Kessels, and Mike Mandel, but if the artist’s style is not immediately recognizable to viewers, the attribution of these works is not known before reading the accompanying exhibition catalogue sitting on the Pier’s front desk.

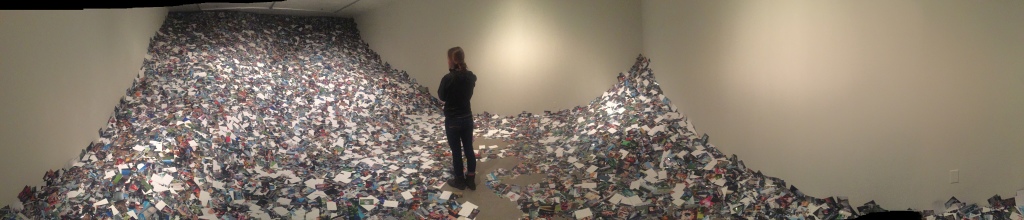

The collection ranges from a collection of hundreds of employee ID badges collected from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s to the contents of family photo albums to images of deer captured by motion-activated cameras in the middle of the forest live-streamed onto a hunting website and re-contextualized in a gallery atmosphere. In one room, Erik Kessels has printed every single image uploaded to Flickr in a 24-hour period. The result is suffocating, and the suggested presence of over one million photographs threatens to crush you as you stand at the base of the unruly mound of seemingly unexceptional (when examined individually) photographs.

In including this Flickr installation, Secondhand encourages visitors to examine our role as curators of our own social media platforms. Every picture posted online adds to our own individually crafted exhibitions – the version of our realities that we want others to see. Through examining the secondhand photos of real people, visitors to Pier 24 have the freedom to create narratives out of a string of somewhat ambiguous images. I found myself projecting character traits and definitive personal attributes to the subjects of Kessel’s In Almost Every Photograph series. People that, without any wall label or explanation to accompany them, are complete strangers with no context to me.

It is this innate, somewhat intrusive, desire to discover personal narratives out of the ambiguous that led me to wander the alternate reality that is Pier 24, completely mesmerized by the who, what, where’s of complete strangers. And when time had passed, and it was time to leave this Shangri-la of photographic wonder, I found myself reconsidering the implications of every photograph, video, and Instagram I have ever uploaded.

Considering what narrative attributes unknowing viewers would project on to me given only a handful of photographs to analyze my social existence, I have come to realize that while many of the pictures I post are significant and exciting to me, they have the potential of appearing commonplace and insignificant in the eyes of strangers. Whether a picture of my dogs, a ubiquitous sunset mupload, an Instagram of my dorm room, or a throwback to me getting ready for my first concert (Britney Spears, with Aaron Carter opening!), these photos would not be at all unique if thrown into the pile of Kessel’s heap of Flickr images. What we post reveals small fractions of our individual identities, but without context or explanation, these small images – these compact groupings of pixels – can be lost in a sea of (quite literally) billions. Perhaps someday, a visionary artist will fish my Instagrams from the depths of the public photographic domain that is the Internet and string together a compelling narrative. Until then, I will continue to document each of life’s twists and turns, sometimes with an added filter, as I create a digital reality of my social self.