Just in time for the end of the most terrifying installment of America’s quadrennial political theater in recent memory, the Stanford Repertory Theater brought us Democratically Speaking on October 20th, 21st, and 22nd. I was left wondering whether we’ve lost our grasp on the ideals of democracy, or whether we’re just better at articulating our society’s problems than those who came before us. Does modern democracy no longer work, or have we only recently learned to hear the voices of those for whom it doesn’t work?

The play was conceived by philosophy professor Debra Satz and Law School professor Barbara Fried, and is composed entirely of excerpts from the works and words of (mostly) Western political thinkers from Periclean Athens to modern America. Actors, both professionals from the Bay Area and Stanford undergrads, read out lines from binders they carried or placed on stands. Since there’s no narrative or commentary except in the ordering and choice of excerpts, the impact of the play came from the creators’ choice to include specific quotes and place them in a deliberate order.

Roughly, the first half of the play was ordered chronologically, with a long section on the Greeks and a shorter one on Enlightenment thinkers. The second half of the play covered the modern period and had a more global focus. It was not structured chronologically but rather by topic, with sections on feminism, black rights, and postcolonialism.

The two sections felt at odds with each other, partially due to the structure of the play. The play only quoted historians a few times, and only in the second half, so the Greeks and the Enlightenment thinkers mostly got to speak for themselves. This is misleading for a few reasons.

For one thing, Greek thinkers in actuality were almost always critics of democracy as a form of government, and very rarely champions of it. The play managed to dig up almost all of the few times the Greeks defend democracy, while giving only passing nods to antidemocratic Greek thought (only mentioning the Old Oligarch and an ambivalent portion of Euripides).

The play doesn’t explain to the audience that democracy meant something very different to the Greeks than it means to us. As Stanford Classics luminary Professor Josiah Ober is wont to say, fifth-century Athenians would consider American government an “elected oligarchy,” not a democracy (and increasing numbers of Americans seem to think the same).

What also doesn’t come across is that (maybe because the Greeks didn’t agree on democracy as the best form of government) none of the Greek thinkers criticize Athenian democracy for leaving out huge swaths of its adult population (i.e. women and slaves).

Other than the depiction of Greeks as pro-democracy, most of this is inevitable if you’re simply quoting Greek texts without commenting on them. The purpose of this section isn’t to give a history lesson on Athenian democracy, it’s just to give the audience something Greek to chew on—and, to be fair, the Greeks are consistently fascinating.

In the play’s excerpt of Euripides, actors Thomas Freeland and David Koppel play two Greeks. One is a Theban who arrives in Athens only to engage the other, an Athenian, in an argument over the relative merits of tyranny and democracy. How can the city be ruled by no one? wonders the Theban. Surely it’s much more convenient, and better decisions will be made, if one man rules alone.

This is a moment we’re reminded of when, later in the play, figures like Mussolini and Lenin again call democracy laughable. One of the strengths of the play is how it’s left implicit—but chillingly clear to the audience—how these words translate to tyranny, to terrifying deeds and scenes from the bleakest pages of human history.

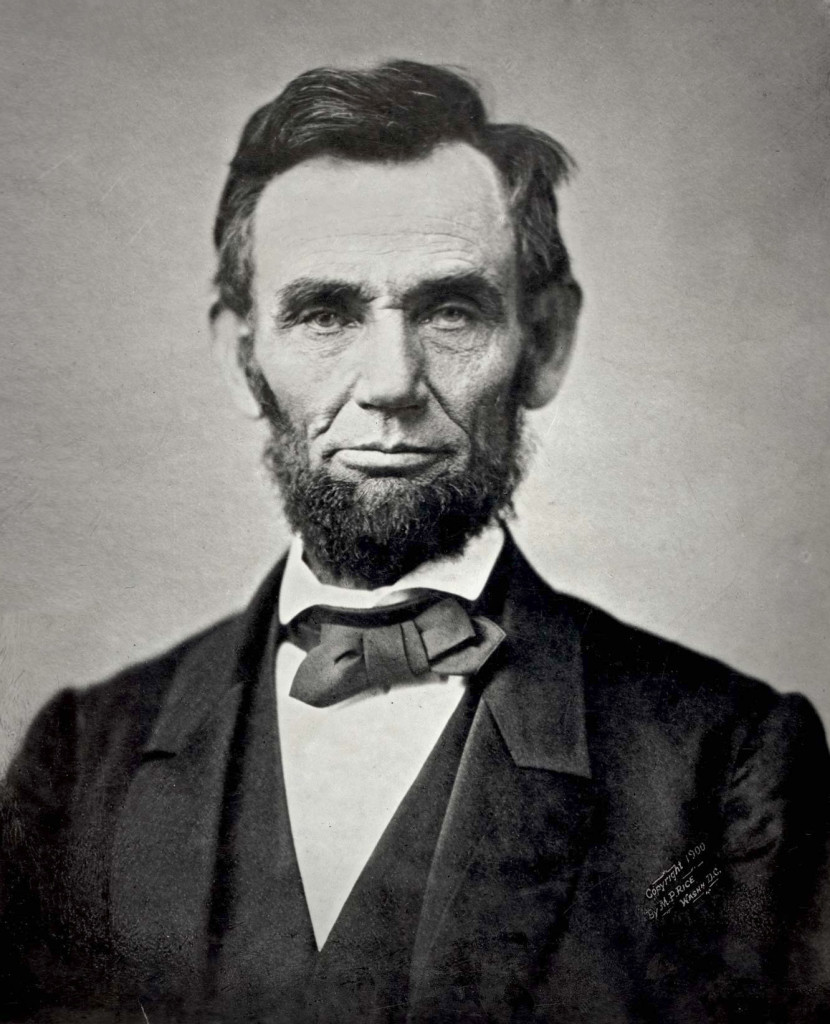

The second half of the play is intentionally much more complicated. We see the rise of American democracy mostly through the eyes of its critics and those it excluded or disadvantaged. The best example of this is the way the play treats Abraham Lincoln, who can fairly uncontroversially be called America’s answer to Pericles, the Athenian statesman to whom is credited a famous speech praising democracy (the Funeral Oration) which is excerpted at length in the first part of the play.

Instead of quoting Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, the play treats Lincoln only by quoting from the famous work of revisionist history by Howard Zinn, 1980’s A People’s History of the United States. The passage paints Lincoln as a prevaricating racist who was induced to freeing American slaves only as a last resort after years of pressure from abolitionists and his generals. It seems that this quotation was meant to challenge the audience’s views on Lincoln as moral hero and liberator, but to me it mostly served to demonstrate what a bad historian Howard Zinn is.

The portion quoted is a complete paraphrase of the historian Richard Hofstadter’s landmark 1948 essay on Lincoln, and such an obvious one that I’d identified the source within seconds of hearing it read aloud on stage. Why Zinn chose to draw from a piece of history writing that was already thirty years old when he wrote his book (and is now almost eighty years old) is unclear, but what’s more frustrating is how Zinn manages to mangle his source’s take on Lincoln.

In Hofstadter’s view (which is also mine, to a degree), Lincoln was indeed what we would now call a racist, and there was a good deal of pressure from abolitionists in his final decision to move against slavery. However, Zinn leaves out Hofstadter’s description of the exigencies of the extremely difficult political climate Lincoln had to negotiate. Neither does it mention what Hofstadter considered Lincoln’s greatest asset: his willingness to adapt, to change his mind from a position of acceptance of injustice to one of action in the name of justice.

So either the play intentionally gave us a very radical take on Lincoln, or its writers weren’t aware that Zinn was leaning on Hofstadter more heavily than Melania Trump leaned on Michelle Obama. In the name of giving the play the benefit of the doubt, I’ll assume the former. In that case, this moment in the play is indicative of character of the second half as a whole: focused on complicating familiar narratives, especially those of America as a moral, triumphant democracy that threw open its doors for all.

One successful aspect of this approach was its ability to throw light on the struggles of women and Black Americans to win the inclusion and rights that were (or else should’ve been) promised to them from the start. The play chose excerpts that emphasized the need to struggle, to make noise and be heard, in order to win rights and a better position. Especially moving were words from Susan B. Anthony and Booker T. Washington, among others, and clever staging ploys, including one that had the men of the cast sitting on a bench watching the women, as advocates of women’s suffrage, speak on the topic. At first, the men jeer and mock the women, but as the speeches go on, one of the male members of the cast has a change of heart; he stands up and applauds Anthony after she finishes a speech, while the other men beside him look aghast.

However, one of the disadvantages of the play’s approach in the second half of the play is how unfair it feels to figures like Lincoln. I personally wonder what good it does to hate the man who signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It certainly doesn’t do anything to make us remember or understand the grim predicament of people of color and women in 1863, or how things have improved (yet, certainly, remained deeply flawed) in the decades since.

What’s more, this treatment makes the play look lopsided. We don’t see Pericles excoriated for leaving out women and slaves from his pretty picture of a free and enlightened Athens. The most unfortunate result of this is that it makes it seem like the Greeks had democracy figured out. It looks to the audience like they had freedom and political power for everyone, while we’re still figuring out how to get back to that.

Of course, that’s not true. The critics of American democracy—may they be long-lived and listened to always—are engaged in broadening the inclusiveness of democracy, and an inevitable part of that is pointing out the fact that American democracy has excluded and does exclude people.

What the play could have done is either been tougher on guys like Pericles, or gone easier on guys like Lincoln. This would remind the audience that there were problems then, and there are problems now, but the reality is this: at least we don’t have human bondage anymore and people vote regardless of gender.

Despite these flaws, Democratically Speaking is a powerful work. It’s a high-minded although temporary alleviation of the woes of this election, many of the particular concerns of which (demagoguery, corruption, xenophobia) go unmentioned. For this clarifying effect we can thank the power of rhetoric. It’s always shocking how contemporary, how apt the words of these political men and women are, as they echo down past the blood and oblivion of history to resound in our ears. Especially so if we read them not as endorsement or criticism of that point in time, but as hope for the future. I recall the words of Pericles’ Funeral Oration, now more than 2400 years old:

“Our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people. . . . When it is a question of putting one person before another in positions of public responsibility, what counts is not membership of a particular class, but the actual ability which the man possesses. No one, so long as he has it in him to be of service to the state, is kept in political obscurity because of poverty.”

When we vote on November 8th, it should be done with the same hope as Pericles had for his Athens: that we can make good on the promise of our constitution, that we can choose our public servants based on ability alone, ignoring not just wealth, as Pericles says, but also gender and race. Democratically Speaking reminds us that government of, by, and for the people isn’t just a notion, a phrase, or even a reality as such. More than anything, it’s a dream. A work in progress.

Images courtesy of Wikipedia