I was about to embark on nearly 24 hours of traveling over the Thanksgiving holiday, so naturally, I had to download Adele’s album on the Super Shuttle at 5 am. I laughed at myself for my priorities: my last minute packing included my toothbrush and 25—except there was no way I was going to forget one of these.

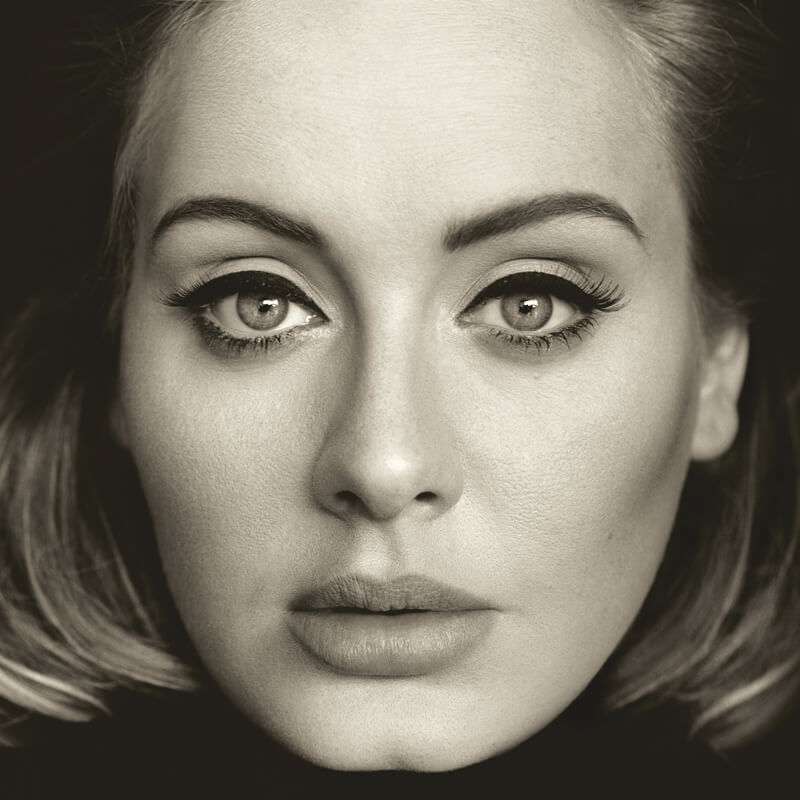

I’ve written on Adele before, have a ton of feelings about past relationships, and enjoy casually butchering power ballads in my rooms: I’m the kind of queer guy that, quite clearly, loves Adele — so of course I was going to buy her album immediately. But we aren’t dealing with some casual diva here; Adele has become a voice that speaks to, quite frankly, anyone with a soul. This fact hit me on the plane before we took off. Emblazoned on both my neighbors’ iPhone screen was Adele’s face (which graces the 25 cover art in a stunningly confrontational portrait). The album had only come out hours before, yet there she was.

While “Chasing Pavements” from 19 and an SNL performance coinciding with Sarah Palin’s guest appearance helped put Adele on the map for North American audiences, it was most likely 21, the album that has sold over 30 million copies, that made all of us download her follow-up 25 the day it came out. 21 was an album that just got people: rage on some songs, deep sadness on others, all falling into a narrative of hurt that was relatable whether that pain was old or new, caused by lovers or simply self-inflicted.

Now, a few years after 21, we were all ready for another therapeutic album that, once again, would just immediately get us, immediately heal us. But that’s not what happened. On the plane, I finished the album and had to start it again. This time around, I wasn’t just replaying “Someone Like You” or “Lovesong” to cry as was the case in 21; when it comes to 25, I needed the whole album. I needed to understand it in its entirety.

This compulsion wasn’t just mine. Adele’s face did not disappear from my neighbors’ screens for the entirety of our transatlantic flight, and when I messaged a friend some thoughts on the album as a “preview” for him, he scoffed, having listened to the album three times already. It’s not simply catchy: if something can keep you engaged on multiple, consecutive listenings, there is an undeniable emotional complexity there. That’s exactly what 25 has.

I’m smugly happy to admit that my review of “Hello” successfully predicted a lot of the emotional growth that underlies 25. However, while that song was an atonement for past mistakes, Adele doesn’t carry that kind of guilt or blame throughout the album. As she sorts out the complex relationships in her life, she alternates between confrontation and comfort, attack and defense. Hearts are broken, but more importantly, hearts are confused.

25 largely focuses on love that doesn’t entirely work. Instead of sticking through it, Adele knows she has to move on. “I want to live and not just survive,” she proclaims at one point, acknowledging her attempts to move away from that pain while simultaneously not really knowing how to. That’s the paradox at the heart of 25: how do we cut off people we once loved? And what if they love us back still? Or what if we love them again?

Adele seems to address these questions, singing from various perspectives in the separation process, but the catch here is that she never really finds the answers. Conviction ebbs and flows, and her lack of coherent response is what makes this album so resonant and also more true to life. Adele made her choices — to stay or leave or to act however she thought she should — but the confidence in her decisions wavers over time. There is a clear difference in tone between songs that examine the tail-end of a relationship and ones that regretfully recall dusty memories after years of silence.

This variability exists even within the same moment. In her lover’s presence, she tells him to stay away…but also wants to be held by him. She ends things in “Love in the Dark” only to invite his embrace two songs later in “All I Ask.” Her declaration, “I can’t love you in the dark” is a powerful juxtaposition to “it matters how this ends / cause what if I never love again?” revealing the insecurities that arise even when love is undeniably gone.

25 explores the sheer irrationality of emotion and, even more importantly, validates our impulses to just lay around and think about the past. Though we all want to feel as powerful as Beyoncé, not everyone has the capacity to strut their stuff to “Single Ladies” immediately after a breakup — and a big part of the pathos of 25 is letting us know that that’s perfectly normal. On days when my heart’s wounding itself and I can’t get out of a now-cold bed, I need to hear the distant voices and haphazard, limp piano playing of “I Miss You.” When Adele tries to preserve ephemeral happy moments in “When We Were Young,” I feel less pathetic dreaming about kisses between paintings at the Anderson Collection — she and I both agree that “it was just like a movie, it was just like a song.” Adele reminds me that breathy whispers, uncontrolled sighs, and barely repressed tears are natural parts of hurt. Emotions happen and that’s okay.

All of this is further complicated, however, since she accounts for her lover’s changing emotions too: he feigns indifference in “Water Under the Bridge,” ignores her in “Hello,” and craves more in “Love in the Dark.” Examining his range of reactions and constantly shifting desires is new, bold work for Adele, whose previous 21 swiftly vilified her ex to the millions of people worldwide she touched with her breakup music.

At points, the album may function as cry-along, sympathy music like the standout singles from 21. But, because of these persistent references to the constantly-changing nature of relationships she’s navigating, there’s also a call-to-action in 25 that 21 lacked. Adele does not just paint a passive picture of being alone and moving on, she talks to her former lovers. She apologizes in the first song “Hello” but regains the upper hand, commanding lovers to do better in “Send My Love (To Your New Lover)” and “Water Under the Bridge.” Aided by dramatic percussion and hand-clapping in these songs, Adele musically builds up the strength necessary to shout at her past.

But this album is tough because at the end of it all, it doesn’t let me mope. Adele’s powerful voice and consistent percussion command us, literally drumming us up. She reels us in with her formula of ballads and hurt, and then forces us to get up and do something. It’s no longer that Adele just sings “Someone Like You” to the ether about how good it all once was. Now, to follow up the laments, Adele takes step to actively make it all better.

I know that this type of confrontation is the right thing to do. As a teaching assistant for a high school summer program, I once told a group of students that the reason we talk about our problems in a public forum is that things get better when we talk about them in the open. That seems to be the logic of Adele’s album. It’s a logic that exists in the desires she fleshes out for her exes. It’s a logic that makes it harder to cut people off. It’s a logic fundamentally based on the personhood of everyone we know — past, present, and future. Adele has changed her script to be more honest and realistic and, above all, fair. I cannot vilify someone who hurt me, since, as Adele reminds us, we hurt them too, even if it’s just in some small way or in some small moment.

But the flipside of this project — the light at the end of the tunnel, so to speak — is the way she allows happiness to sit side-by-side with regrets. “Sweetest Devotion” is pure love, filled with children’s voices and a sunny, bubbly atmosphere despite the sorrow and anger of the earlier songs. It is the last song we hear on her album full of tensions and contradictions and apologies to the past. Maybe Adele, on balance, is happy. Maybe, on balance, I’m happy too. Adele accounts for the type of life I lead living with anxiety: I’m drinking wine with a guy I really like — and I’m totally into it — and simultaneously fighting memories of how rude I was to a similar person months ago, a person I can no longer apologize to. Contentedness and tension are not paradoxical. Sometimes I need to be reminded that one does not ruin the other: I’m allowed to worry and think through things, and 25 asks me to do that. Since maybe learning from a painful past is what makes us even happier today.

Adele’s universality is back, but it also brings with it a responsibility to do better. Just as she tries to reconcile with the people of her past, she wants us to do the same. It might not always work — sometimes people fully move on even if you don’t, or sometimes you do and have to deal with having left people behind — but at the end of the day, we have to try. 25 cycles through a whole range of emotions, headspaces, and times, but the entire album guides us through healing. We should grieve, we should mope, but we also need to talk things through. Adele challenges us to do that.

Maybe I’ll make some calls soon.

oui

November 24, 2015 at 7:56 pm (2 weeks ago)I hate to be that person, but…

I’m gonna be that person.

Do you mean “Hello” when you say “Home”?